This is a guide to the bizarre, complicated story of NieR and Drag-on Dragoon—with all their various side materials.

A not-so-brief real-world history

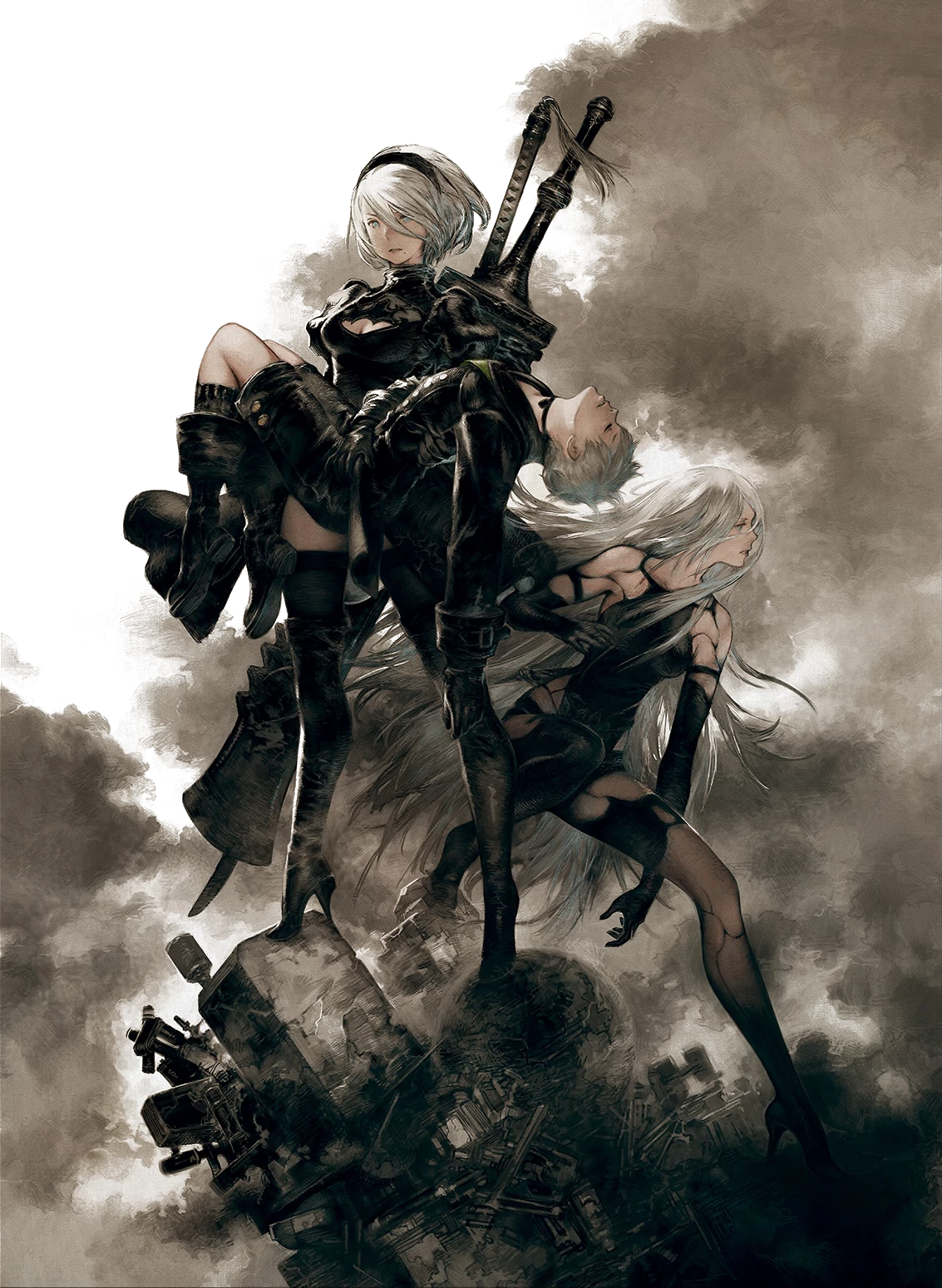

A promotional image for DoD3 featuring the protagonists of the four games thus far (artist unknown)

In 2003, Dragon-on Dragoon was released for the PS2 by the little-known studio Cavia. A few months later, an English translation was released under the title Drakengard.

A project of an underfunded, inexperienced dev, combining a Dynasty Warriors-style musou game with flight simulator sections in the vein of Ace Combat (which the devs had previously worked on). It didn’t have much reason to be a hit—and it wasn’t! But it found a small, dedicated fanbase, drawn to its comically dark setting, unsettling and dissonant soundtrack, and vivid and awful protagonists. It was followed by a much less interesting sequel, with Yoko Taro withdrawing to a cutscene director position. For a while, that was that.

Then came NieR in 2010.

NieR: Replicant for the PS3 and NieR: Gestalt for the XBox 360 sampled just about every genre of game, from shmups to text adventures, but mostly they were a third-person action-RPG. Originally conceived of as a fairy-tale world, it ended up being a kind of post-apocalyptic sci-fantasy. The story is powerful and tragic, Yoko Taro coming into his own as a writer with a lot of moments that hit your emotions like a train. Like DoD, the cast was unusual and striking - but instead of portraying a group of ‘crazy’ monsters like in DoD, they are deeply sympathetic outcasts whose situations follow from cruel circumstances. Okabe Keiichi joined on to make an incredible choral soundtrack, and Emi Evans got involved as the singer, creating a whole ‘chaos language’ for the project.

Sadly, a combination of kinda dodgy gameplay and a bad landing with critics meant it was, once again, not a hit. But it picked up another dedicated fanbase in the people who played it far enough to fall in love, and created a surprising amount of spinoff media, most notably Grimoire NieR and an audio drama CD featuring the voice actors from the game.

At some point after that, Cavia folded and Yoko Taro went to work for Square-Enix directly. Drag-on Dragoon 3 was a 10th-anniversy prequel to DoD, standing somewhere between a character action game and a musou game like the original. It took the art direction somewhere a lot more anime than the dourly European DoD, and the tone became much more ‘darkly comic’ than ‘grimdark’. But it’s still very much a tragedy: the six Intoners, despite their more or less noble intentions, are each caught in a different model of terrible relationship, each chasing their flaws to a miserable end.

DoD3 has a brilliant soundtrack (specifically in the Intoner battles featuring the YoRHa idol group, and Hana Kikuchi’s beautiful ‘Black Song’) and a striking aesthetic. It’s got a ton of fantastic moments and, if you give it the chance, a really good story. Sadly, it’s let down by competent but extremely repetitive action gameplay—so once again, it got average reviews and unremarkable sales. Yoko Taro seemed destined to make small cult followings, but never a lot of money.

In the process of making the music for DoD3, Yoko Taro got the idea of getting involved in the idol scene (per Rekka Alexiel). So Yoko Taro, Okabe Keiichi and Iwasaki Takuya assembled an idol group consisting of vocalists Aino Eri, Ichikura Yuna and Sakurai Tamaki, under the name YoRHa. In the liner notes for their songs for DoD3, Yoko Taro experimented with the concept of androids fighting ‘machine life forms’ (living machines, ) in a distant future. This is how the Automata concept got started…

A couple of years later, Yoko Taro expanded the story of the idol group into a musical stage play, also titled YoRHa. The first run of the play had a tiny budget and limited costumes compared to later runs, but the story and incredible aesthetic carried through.

The protagonists of NieR Automata (official art, artist unknown)

In 2014, Yoko Taro got another chance to make a game, despite Square-Enix’s wariness. PlatinumGames, a studio renowned for games like Bayonetta and Metal Gear Rising, were very keen to build a NieR game. A bunch of people who worked on NieR headed out to Osaka… and it finally paid off. This time, for once, the game was a real hit: all the elements (some of Yoko Taro’s best emotional writing, an incredible soundtrack by Keiichi Okabe, J’Nique Nicole and Emi Evans, a unique gothic lolita aesthetic, and extremely solid character action gameplay) came together, and people went bananas. Despite being a small side project for Square-Enix, the game went on to sell (at time of writing) a good four and a half million copies. (This is where I came on, and got deeply obsessed with NieR.)

Realising they had a hit on their hands, Square-Enix started spending a lot more on NieR. There were a series of concerts featuring short audio dramas, which wrapped up the story of Automata; there were short story collections; there was a much higher-budget production of the YoRHa musical (called version 1.2), and a whole new stage play called Shounen YoRHa (YoRHa boys). They’re presently working on a new, genderflipped production of the musical called YoRHa version 1.3a, which apparently takes place in an alternate timeline.

Yoko Taro himself, meanwhile, became part of the whole marketing effort: he started regularly appearing in promotional videos, conventions etc., playing up a joke character where he’s self-effacing, horny, and generally a bit of a troll, and always wearing a spherical mask that covers his face (an evolution of a sock puppet he’d used before). But he also appears at game developers’ conferences, talking a bit about how he wrote NieR, which is worth a watch. Yoko Taro and his wife Yokoo Yukiko have also written for the mobile game SINoALICE, which features occasional crossovers with NieR and DoD characters.

The most recent NieR material at the time of writing is the YoRHa: Dark Apocalypse raid series in the MMO Final Fantasy XIV, and a world concert tour which managed to just sneak in before the COVID-19 catastrophe hit. And, as of a couple of days ago, a remake of NieR Replicant has been announced, with Yoko Taro and Yosuke Saito on board, Taura of PlatinumGames directing the gameplay, and Keiichi Okabe composing new music. We also have a new mobile game called NieR Reincarnation with most of the same people.

So it’s a good time to catch up on what happened so far…

What’s all this then?

For people who arrived at the series with Automata, looking back on the rest of the series - not to mention the side materials - is a lot. The games are spread across three consoles, and then you get the side materials: books of short stories such as Grimoire NieR, two manga series, novelisations, an audio drama CD, two stage plays, dramatic readings from the music concerts, a raid series in Final Fantasy XIV… and unfortunately many of these are only available in Japanese.

Thanks to the efforts of various fans (in particular, Rekka Alexiel and Kho-Dazat), most of these side materials have been translated into English. As well as having translated a number of the stories herself, Rekka maintains a detailed timeline, and a helpful flowchart to show how all the different parts of the series fit together. For Automata specifically, there is also The Ark wiki which collects many stories and resources.

But where do you even begin, and how the hell does it all fit together? The aim of this series is to be a slightly more fleshed out timeline, with links to all the stories and fan translations, in their appropriate context.

We’ll begin at the beginning: Drag-on Dragoon 3.

Comments

fall (fd15152aa86a66aabc076e11c846a0d9)

i had a really good time watching you play the first story sequence of the nier remake! altho i missed a lot of the ending >w<

the gender-flipped musical sounds really interesting o:

thank you for this detailed write-up!