This is the seventh part of a series of articles on The Tyrant Baru Cormorant—part review, part meta, part commentary. For intro and links to the others, go here!

In this one, we consider what Baru’s whole life has built up to: her plan to ‘butcher’ the Masquerade, and bring about a world not ruled by its colonialism.

- Barhu’s big plan

- An economic cancer

- History lessons!

- The reason for empire

- The motor driving ‘will’

- Where’s all this going?

- Speculative speculation

- So Bryn, we’re up to the 10k word mark. Give us an answer—will it work?

Barhu’s big plan

If, as we’ve seen, the Masquerade thrives by making everyone dependent on participating in its growth, how can it be destroyed without killing all those who’ve come to depend on it? For so long, Baru could not see an answer; she resigned herself to a vision of apocalyptic war as the only alternative to Falcrest achieving ‘total causal closure’.

In this book, in a meningitis-induced sex dream about her dead girlfriend, she finally figures out her answer: a plan which plays to her strengths, which she believes can bring down the Masquerade without taking everyone else with it. It’s one which plays to her passions and skills, born from her childhood in a trading port and belief in the potential for trade as a good thing, linking people together; a plan which she can pursue under Falcrest’s nose without them realising what she’s hoping to achieve.

At least, that’s the idea. Most other people are not convinced.

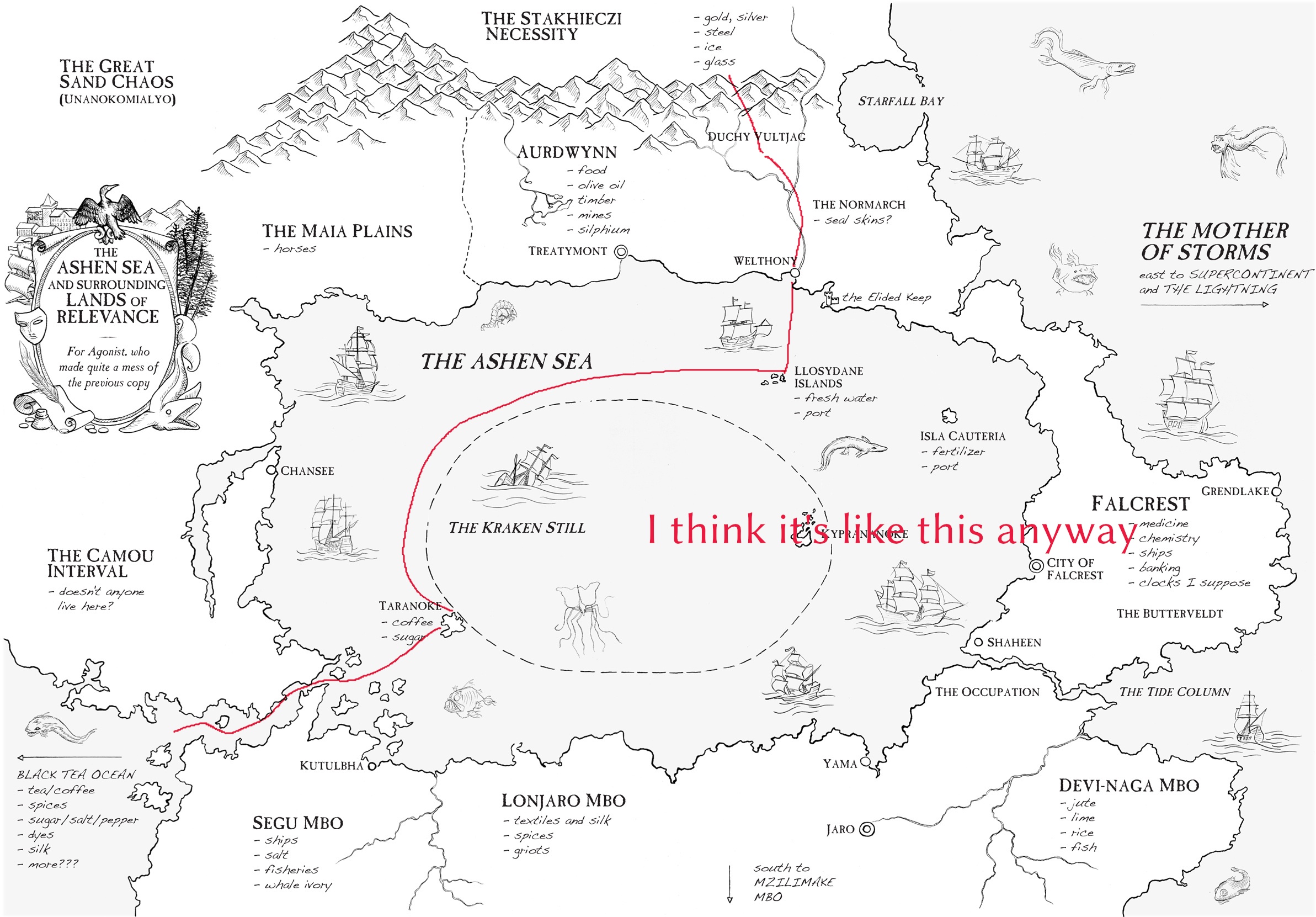

Barhu’s plan begins with a new trade route, between Falcrest and the Oriati Mbo—but one that she controls by virtue of an Emperor-granted monopoly. Powered by the enormous wealth she gains from this, she can increasingly take control of the Falcresti economy. This new trade route would link up most of the places we’ve visited in the story so far, bringing immense profit to each:

The route is supposed to connect Segu Mbo in the Southwest to the Stakhieczi in the north, via Taranoke in the Southwest, the Llosydanes in the Northeast, Welthony Harbour in Aurdywnn north of the Llosydanes, and finally passing through the Duchy Vultjag.

Barhu keeps the second part of her plan close to her chest, but she finally explains it in a final meeting with the Brain:

Baru's plan in her own words

“This adjacent number is my estimate—a conservative one, I might add—of the percentage of total world trade, by value, which would fall under this concern’s monopoly. I know that thirty-five percent is a very large number. Again, I assure you it is realistic.

“And here is the percentage of Falcrest’s total economy which I believe we could ultimately entangle in the well-being of our concern. I expect we will pass the fifty percent mark within ten years.

“Once we have made our initial stock offering, I anticipate a frenzy of speculative trading: This speculation will be driven by the basic soundness of the concern’s position—we have a monopoly on a highly profitable trade, after all. I will drive speculation by issuing credit to investors, allowing them to buy stock through an installment plan. Details if you want them.

“This is where we begin to get tricky. Financial power means we’ll have considerable access to the Twelve Ministries and Six Powers. We’ll be able to buy our way into Parliament and raise our own merchant navy. But my ultimate goal is complete capture of Falcrest’s wealth, and to do that, we need to access the personal fortunes of the Suettaring elite.

“To secure that access, I plan to make my trading concern into a tax haven. The wealthy will not want to pay a share of their hard-won fortunes to Parliament. I will offer them a simple way to avoid it. Moving the money into my concern, and from there into Oriati Mbo, will place it beyond taxable reach. It can be invested in various assets there, and they can recover it whenever they want thanks to the, ah, fluidity of the Oriati hawala trust-banking system.

“It won’t escape your notice that moving this money into Oriati Mbo places it in range of your use. We can skim, launder, and misplace funds to meet whatever requirements you have. You will be able to buy all the metals, materials, and supplies required for an effective war. In effect, the total wealth of Falcrest will become your personal lending bank.

“And when the time is right, when I send the signal, you will strike. Not at Falcrest—a land invasion across the Occupation would be disastrous, a crossing of the Tide Column suicidal—but at the trade.

“There will be no Oriati civil war. No second Armada War. No Kettling. No democide and disaster. Let me make a bubble. Let me fill it with all Falcrest’s strength. And then help me burst it.”

- drive Falcresti investment into her trade monopoly by encouraging speculation

- encourage use of Oriati assets as a tax haven for the Falcresti elite, and thus take control of most of the Falcresti economy

- siphon out a portion of this enormous amount of money from Falcrest using fraud

- use these funds to arm the Oriati

- the Oriati will attack Falcresti trade, cutting Falcrest out of the equation entirely

- the Empire, now bankrupt, will be unable to survive

The Brain is not persuaded by Barhu’s plan. While Barhu is obsessed with numbers, she drops the title of the book, and reminds her of the unspoken cost of capitalism:

“You want to be a tyrant,” she said.

“I prefer the term tycoon,” Barhu suggested.

“No. You will be a tyrant. You will be a creator and protector of tyranny. Do you understand what Falcrest does to us, if they have the access given by trade? Trim is outlawed. Family land is bought up and turned to cash crops. Children are worked in the fields. Men are killed and their killings blamed on their own conduct. Women are stripped of their children and brought into prostitution. Their sons are soldiers. Their daughters are sent as maids to the houses of the rich. You are asking me to open our doors to a pack of rabid dogs.”

In my somewhat strained metaphor of Kimbune’s Theorem, Barhu hopes to redirect the vast economic power of Falcrest not to expansion, but to transform it into something different. As she sees it, the vast expanding wealth of Falcrest could be stolen and transformed into vast wealth of Taranoke, Vultjag, the Stakhieczi, the Mbo; we later see her dream of a future world in which a kind of cosmopolitan scientific modernity would develop, complete with uranium-powered carriages, surgery anaesthetised by opiates, and ‘meat golems’ controlled by electricity. The people of this future would be diverse, but all the wealth the would enjoy came from trade.

In short, a perfectly bourgeois vision of the future.

The Brain is, quite rightly in my view, antsy:

“The best way to break a mill is to burn it down, Baru.”

“Not if you want to keep building mills and making flour! The reason Falcrest is winning is because its ways are stronger! I can steal that strength!”

“But it is still Falcrest’s strength. It is still that monstrous pillaging force which treats people like coin and coin like people. And if you try to wield it you are seduced by it. Take Alu into your body instead. Consecrate yourself into my trust.”

“Damn you,” Barhu hissed. “I can do so much more than carry a plague and die young. Don’t you see? The concern that rules this new trade could be mightier than the Republic itself! And I will own it all! I can force Falcrest to give justice to those it’s conquered!”

“Nothing you own by Falcrest’s means is owned by anything but Falcrest. When you think you possess them, that is when they possess you.”

In our own world, we have not exactly seen capitalism severed of empire. The old European empires have officially relinquished their holdings, but not before installing capitalist means of governance which live on; all of us now dance to the strings of the world economy. And the beneficiaries of that economy haven’t changed all that much. Capitalism, as an abstract force, annihilated prior modes of self-sufficient existence just as surely as Falcrest’s ships and incendiary weapons.

But Barhu would be at the top this time! Ready to technocratically ensure that nothing bad comes of her trade concern. So that would make it OK right?

The Brain does not, admittedly, have a much better plan. Her own method is to render herself a sort of messiah—by casting her current body in bronze, and having another person with the same tumour take up the cause—and stoke the various Mbo into war against Falcrest.

The question of whether something other than capitalism could have been born of the end of feudalism is one that we will never be able to definitively answer. In the history we ended up having, capitalism won, at this point anyway. The world was proletarianised: slowly, sometimes through the mindless action of the market but often through the deliberate efforts of the “workers’ movement” and its representatives, the ‘peasantry’ (self-sufficent farmers) that once made up almost the entire world population has been dissolved; at last all of us now depend on the market, and are thereby forced to work for a wage.

This is a process Baru, back in Monster, sees in positive terms, speaking to Svir of her plans to link Aurdwynn into the world market:

“Once their economy values currency instead of land, the peasantry will be able to profit and save off their own labor instead of tithing their incomes for protection—”

Here, we see her plan extend to the world. Barhu, the daughter of traders, the accountant… she cannot imagine how this trade would leave people not with opportunities for saving and profit, but propertyless proletarians structurally necessary for the whole machine to work. The hypothetical meat golems will do the work, right? Just like one day, we’ll be able to stop working because of robots and asteroid mining and clever technocratic computers, as the FALC advocates promise.

So as satisfying as it is to see Barhu absolutely annihilate Cairdine Farrier (we’re getting to that) and get back on her feet, it’s hard not to believe that the many people who point to the ghost of Falcrest in her plans are absolutely right. A ‘better’ Falcrest, perhaps: one without the eugenic obsessions and dreams of centralised control, but still a power that subsumes everything to its expansion.

An economic cancer

I’ve drawn one grandiose metaphor, linking the economic transformation that Barhu hopes to accomplish to the way, with an imaginary argument, exponential growth and decay becomes a contained circular orbit. But an economy is not just a point in a plane; it is a living system. And the book furnishes us another metaphor…

Elsewhere, Barhu muses (while pretending to be lobotoimsed—more on that shortly!) on what it was that enabled Falcrest to rise to its position in the world. She considers many angles, but one of them is Falcrest’s financial system:

There was so much she could say. The matter of money, Falcrest’s wholesale adoption of paper fiat notes and liquidity banking, which allowed them to move value more efficiently: you could not raise money from your people to fund an expedition if all their value was locked up in farmland and lumber and milk. But when it was stored in paper notes in banks then you could borrow from the people without actually taking their property.

Why do we organise our lives around the fiction of money at all? The details of the answer may vary depending on your preferred economic school, but all answers come back to the behaviours that money creates. Money defines a system of impetuses to act, and coordinating dynamics, which take a bunch of people living out our lives and bind us together into an economy moving towards, more or less, a common goal. If the Chartists (briefly described in Graeber’s flawed but fascinating book Debt) are right, and money was born from early states and kings to feed their armies, it was because of its utility in making sure food is grown, organised, transported etc.

So looking past Barhu’s explanation of the plan in terms of abstractions like ‘wealth’ and ‘money’, what she aspires to do is to inject a different organising principle into that developing process—a new system which will, though born of the same substance, rapidly grow to take control of its host’s functions, ultimately (she hopes) fatally.

We could, if we wanted to be cheeky, say she wants to give Falcrest cancer. But like the transmissible cancers of the Cancrioth, like real immortal cancer cell lines such as those taken from Henrietta Lacks, her economic cancer (she hopes) will outlive its original host.

So is she killing Falcrest, or rendering it immortal?

Maybe history can be a guide…

History lessons!

At the end of the book, while listing the scientific basis for their various ideas, Seth speaks briefly to the plausibility of Barhu’s plan:

The economic power of Baru’s notional trade concern is hardly exaggerated. Nor is the possibility of the near-total destruction of an imperial economy by mismanagement on the part of a powerful few: interested readers may look into John Law’s time in France and the neighboring South Sea bubble in England.

Well, I am an interested reader. Let’s find out more. (With apologies for people who aren’t concerned with 18th-century economics.)

But I know you like to read about 18th century economic bubbles...

John Law in France

John Law was a Scottish economist. In the events discussed, Law created a bank that bought up most of France’s debt with the then-novel paper money, and consolidated all the trading companies of French ‘Louisiana’ into one Mississipi Company in the 1700s.

John Law's system: fiddly details

The region the settlers called ‘Louisiana’ was of course actually the home of an enormous variety of people, among them the Choctaw, Natchitoches, Tangipahoa, Houma, Kadohadacho, Taensa, Natchez, Caddo, Acolapissa, Ishak…

None of these people were of much interest to John Law, who saw the potential vast profits of Louisiana as a key element in his elaborate currency experiment. So what was he trying to do? I’m going to do my best to answer, using sources like this paper (scihub link) and this page.

Our story begins in France, which has recently lost its big famous king Lous XIV. They’ve spent basically all their gold and silver money on wars like the War of Spanish Succession, and so the new regent of France is receptive to the economic theories of a Scottish economist called John Law, who was excited for the potential of paper money.

They didn’t jump in wholesale at first, using traditional means of managing their debt, like devaluing the currency. But John Law was given a bank, which would buy up the French state’s debt bonds in return for shares in the company as initial investment. In its function as a bank, it issued notes: merchants could bring bills of exchange (IOUs, basically) and get paper bank notes in return. At first, the bank notes represented a claim to a certain proportion of gold and silver coins from the bank’s reserve. As John Law had predicted, he could put many more notes in circulation than the bank’s reserve and still keep a functioning bank. Over time, he and the regent attempted to phase out the old currencies and turn the paper money into the only legal tender of France; John Law’s bank even took over such functions of the state as tax collection!

The second component of John Law’s ‘system’ was his Mississipi Trading Company, which subsumed various existing French trading concerns to hold a monopoly on exploiting Lousiana, which Law believed held an enormous amount of mineral wealth. This is where things started to go really wild. At first, Law sold shares in his company in return for those government debt bonds. He then gave a big loan to the French government, financed through sale of shares for bonds, which the French government used to pay off the rest of their debt— they now owed it all to the Company. But soon, he was getting monopolies left and right to provide more secure funding than these government bonds—until he basically controlled the entirety of French trade, especially the planned exploitation of Louisiana.

Why would you want these shares? The shareholders would be entitled to dividends, and the belief in the vast profits soon to come from Louisiana kicked off a massive speculative bubble, kicking the share price up to absurd heights. And once the share price was going up, people wanted to have shares to cash in on the capital gains later. Paris went wild with people trying to get close to John Law, there was fighting on the street, people died…

So how did the bubble burst? I admit I don’t fully understand this part of the paper, but Law believed that he had to keep his share price high in order to achieve his various financial goals, such as the bank offering low-interest loans (low interest being something he believed a sign of a healthy economy). So as the speculative frenzy began to top out and people started to lose faith in the whole thing, and more people tried to cash in their shares before the going got bad, he ‘pegged’ the value of the shares—which means basically he ordered the bank to buy shares at 9000 livres of banknotes, which set a floor on what they’d be worth. But all these banknotes being issued to buy his own shares massively inflated the currency.

And it totally died when Law started fucking with that exchange rate to try and deflate the currency again. This caused such panics and uproar that he lost his government post and eventually fled in exile.

John Law’s ‘system’ collapsed after massive currency inflation and a loss of confidence in both his shares and paper money, ruining many investors. But what happened to the parent empire? They had to clean up the mess of the company, and basically ended up where they’d started in terms of debt—deliberately committing to pay certain increased debts rather than default on the whole thing. The whole episode helped discredit the monarchy, and apparently threw a severe wrench in the development of “French capitalism and industry” according to those capitalists in the second link.

So for individual French bourgeois and nobles, apparently it was tremendously bad news. I don’t know how strong a link you can draw to the French revolution, but perhaps it played a role in doing for the monarchy entirely.

But if we’re comparing Baru’s plan, the real question is—how did it affect French colonialism? It did not stop the French from ‘developing’ their colony in ‘Louisiana’ to some degree—perhaps not to the degree they would have if not for Law’s financial shenanigans, but it didn’t send them packing either. The French revolutionary government—which is in some part clearly the model for Falcrest—still held colonised territory around the world until the anti-colonial revolutions of the 20th century.

Of course, the speculative bubble is only part of Baru’s plan; but what we see here is that a speculative bubble alone, though on a scale comparable to the French government’s massive debts, is not enough to kill an early modern empire. Just to wound it.

South Sea bubble

The South Sea bubble was at first an insider trading scam, but grew into a kind of response by the English to the new financial experiment in France, during a time when Britain was at war with Spain. The colonial monopoly it pursued was the slave trade: the ‘South Sea Company’ would transport African slaves to South America, at the time still under the control of Spain and Portugal. It provoked a similar investment bubble when, much like John Law’s company, it started taking over government debt.

Unlike John Law’s bubble, which was driven by flawed economic theories but a sincere effort to… make France better at colonialism, hooray?… the South Sea Company was pretty much a scam from the outset, though a scam which played on rich British peoples’ enthusiasm to get rich off trading abducted humans to the most horrific life imaginable, so don’t feel much sympathy for anyone involved.

The South Sea bubble

After the same War of Spanish Succession, money was tight for the government of Britain. Previously, government debt had been handled piecemeal, with different departments taking out loans from the Bank of England (a private company) whenever they needed. A scheme was hatched to deal with this by our main dude Robert Harley, who held the rather grandiose-sounding title of Chancellor of the Exchequer. (British politics is full of pompous names like this. For example, later in the story there’s mention of Auditors of the Imprests.)

The plan was relatively simple: they’d make a new company, the South Sea Company, which like John Law’s system would sell shares in the company in return for getting control of government debt at face value. Government debt was not particularly valuable at the time because people didn’t expect it to be repaid. To entice people, there had to be some belief that the company shares would be worth having; this was secured with the redistribution of debt payments from the government, and later the promise of exclusive right to trade slaves to South America, then still under control of Spain. The conspirators had little expectation there would actually be any profitable trade, but they needed investment for their scheme to work.

The initial buying of government debts at face value offered a lot of potential for profit for our main conspirators. Those in the know about the new Company could buy up debts on the cheap before the big announcement, and then shortly sell them to the Company for their nominal value in Company shares.

One thing I was surprised to find out was that Isaac Newton owned £22,000 of shares in the company. It’s not known if he got rid of them before the bubble burst. But man, as much as I knew about his brutal treatment of counterfeiters and fellow scientists, ‘investor in the slave trade’ is kind of widely elided from history! What the fuck…

After the end of the war with Spain, England got its hands on the right to trade slaves to Spanish colonies, previously only available to France, and set up a number of slave-taking ‘factories’ in West Africa. Although this was not the real intention of the company, it went ahead and bought 34,000 people over the 25 years of operation, mostly in the first few years. Of these people, about 30,000 survived the trip (so 4,000 died of disease, punishment, drowning, etc. en route).

This literal decimation was considered a good survival rate by the standards of the ‘middle passage’.

The company’s trading activites ended in 1718 following the start of another war with Spain. That was not the end of the company, but rather the beginning of the bubble. Hearing about John Law’s activities in France, they attempted to consolidate more and more debt into shares in the company. For the holders of debt, the advantage was that company bonds could be readily traded, meaning they were far more ‘liquid’ than other ways of owning wealth; the bonds were in effect a kind of paper money.

Here’s how it worked: the company would first create a certain amount of stock whose value would equal the debt at the time, in advance of the day they were supposed to swap it for government debt. On the day of the sale, their rising stock price would mean that the stock they’d created would now be worth more than the value of the debt. So they’d have some stock left over, which they’d sell, and make a profit.

After all was said and done, they managed to turn most of the existing government debt into stock in the company.

Their next act, in the early 1720s, was to try to inflate the value of their shares as much as possible by talking up the great (false) potential for profit at slave-trading, and dicking around in Parliament to make sure various politicians saw the success of the company as in their interest. This included getting a bunch of friendly ministers to defend the conspirators’ bank, the weirdly named Hollow Sword Blade Company, from investigation. In the end, this meant that the version of the ‘Bubble Act’ that was passed mostly served to suppress competition, boosting their shares even further.

Naturally, the bubble collapsed, causing a wave of bankruptcies, including small banks and goldsmiths who couldn’t honour loans anymore. Once it did, the conspirators got pulled up by parliament for fraud and variously stripped of their positions and most of their wealth (meaning they went from stupendously rich aristocrats to moderately rich aristocrats). Robert Walpole, the First Lord of the Treasury later known as our de facto first Prime Minister, was put in charge of unfucking the whole thing and bailing out the investors.

Naturally, the collapse of the speculative bubble, while it certainly did for various politicians, certainly did not put an end to British colonialism or slave trading. I don’t know if any particular country managed to escape the various speculative bubbles of this period. And on that note, it would be resistance of the enslaved people, such as the Haitian revolution, not some sudden British benevolence, which finally put an end to the slave trade in the much later, in the 1830s.

What to conclude?

John Law got France to go bananas over a colonial expedition that found no resources to exploit; the South Sea bubble got England to go bananas over trafficking slaves to their ostensible enemies. They bankrupted many of the rich of their nations, perhaps even set the stage for the later fall of the French monarchy (though there were many other factors!), but neither episode stopped the empires from functioning as empires. At best, they just slowed them down.

Of course, the nakedly obvious conclusion is that colonialism is utterly, unimaginably evil. But that probably goes without saying.

As far as our world of fiction is concerned, Barhu’s plan is to create a similar speculative bubble to capture most of the wealth of Falcrest in her own colonial monopoly venture. By getting Falcrest to move their wealth offshore, she can create conditions for the Oriati to seize it.

But in practice, what would that mean? We know Falcrest has a fiat currency; what would actually be seized? Military control, perhaps, over the trade in actual, physical goods—and thanks to Barhu, Falcrest would not be able to finance a war to take back. I think that’s the idea, anyway. I guess we’ll find out in the fourth book.

The question that seems all the more pertinent after reading those histories is, would that be enough?

Money is, after all, a fiction. Certainly a powerful fiction, much like the Cancrioth’s magic—a system for getting people to behave in a certain way, a complex of beliefs and behaviours that reproduces itself.

But it is people who sail a warship, not money. Money makes sure that someone prepares them food to eat at the end, money gets those people to sail the boat, but the money is subject to change. When John Law wrecked the French financial system, the French government didn’t disappear: they set to work redoing the money to keep everything ticking over.

In this book, financial shenanigans are enough to force Falcrest’s navy to return to dock (a power play by Falcrest’s Parliament we haven’t yet discussed). But if Falcrest’s control over the world was truly at stake, would the economic snafu be enough to prevent them mobilising all force necessary to take it back? I guess Barhu, no stranger to war economics, thinks so: if Falcrest cannot pay their sailors’ wages, can’t move the chemical ingredients to the Burn workshops, outfit their ships, and do all the things that drive a war economy, they won’t be able to take back any control.

But the social relationships of domination won’t disappear as quickly. As Barhu herself notes, the animating principle of Falcrest is not its money, but something else…

The reason for empire

I said earlier that the series was framed by Baru’s early question of why them, and not us? Why did Falcrest arrive at Taranoke, and not the opposite?

I will quote her full answer now, since it’s one of my fave passages of the book:

Why Falcrest, and not Taranoke?

There was so much she could say. The matter of money, Falcrest’s wholesale adoption of paper fiat notes and liquidity banking, which allowed them to move value more efficiently: you could not raise money from your people to fund an expedition if all their value was locked up in farmland and lumber and milk. But when it was stored in paper notes in banks then you could borrow from the people without actually taking their property.

There were the ships, the superb rigging and coppered hulls and the chemistry of citrus and salt that kept the crews alive to sail, and the fearsome laboratories that produced the Burn. There was the culture of desperate and syncretic inadequacy, fear of the world outracing Falcrest, which had stolen the best of Stakhieczi astronomy and Oriati scientific philosophy. And the culture of revolutionary bloodshed, willing to use living bodies to discover the causes and cures of disease, to test which substances would do harm if used in piping, food, cloth.

And Lapetiare and his coffeehouses, where the art of debate grew from spectator sport to revolutionary spark, where the stockbrokers did their trading now. There were the pigs that gave Falcrest the annual flu, which made the Masquerade’s collective immunity so vigilant, which laid flat the populations of every new province Falcrest seized. There were the canals and the waterways, the ancient expertise at managing tsunami and flood that became the modern engineering that turned the mills that made the flour and the soybean meal that put the calories into the workers. And the sewers. And the aqueducts. And the republican government, which shifted the flow of a Parliamin’s corruption and favoritism from fellow elites to a Parliamin’s constituents, so that corruption at least helped the common people sometimes.

But all of those things were just limbs and muscles on the beast. They explained how Falcrest was conquering the world but not why. A strong man might have the ability to strangle or force a weak man. But nowhere was it written that the strong man was fated to kill or enslave that weak man.

Would Taranoke, given all these advantages, have gone to Falcrest, subverted and enslaved it, made it part of a Taranoki empire?

No. And the Oriati were the proof. The Oriati had their own heinous history, their own spasms of conquest: but for much of their millennium of unsurpassed worldly power, they had kept to their own borders and their own internal struggles. Their voyages had been for exploration and trade. They had been good neighbors.

Aurdwynn had of course washed itself in blood. The Maia had come to conquer, the Stakhieczi had counterinvaded to preserve the great green breadbasket that fed them. So you might be tempted to say that wherever cultures meet conflict was inevitable. But they had been two rival homelands at war over the middle ground; neither had ever made a possession of the other.

Yes, people had always been evil nearly as much as they had been good. Yes, happiness was rarer than suffering—that was simply a fact of mathematics; happiness required a narrow range of conditions, and suffering flourished in all the rest.

But Falcrest was not an innocent victim of a historical inevitability. Empire required a will, a brain to move the beast, to reach out with appetite, to see other people as the answer to that appetite, to justify the devouring of other peoples as right and necessary and good, to frame slavery and conquest as acts of grace and charity.

Incrasticism had provided that last and most fateful technology. The capability to justify any violence in the name of an ultimate destiny, an engine to inflict misery and to claim that misery as necessary in the quest for utopia. A false science by which the races and sexes could be separated and specialized like workers in a mill. And the endless self-deceptive blind guilty quest to justify that false science, so that the suffering and the misery remained necessary.

Falcrest had chosen empire.

Or, to cut it a little shorter…

But all of those things were just limbs and muscles on the beast. They explained how Falcrest was conquering the world but not why. A strong man might have the ability to strangle or force a weak man. But nowhere was it written that the strong man was fated to kill or enslave that weak man.

…

But Falcrest was not an innocent victim of a historical inevitability. Empire required a will, a brain to move the beast, to reach out with appetite, to see other people as the answer to that appetite, to justify the devouring of other peoples as right and necessary and good, to frame slavery and conquest as acts of grace and charity.

Incrasticism had provided that last and most fateful technology. The capability to justify any violence in the name of an ultimate destiny, an engine to inflict misery and to claim that misery as necessary in the quest for utopia. A false science by which the races and sexes could be separated and specialized like workers in a mill. And the endless self-deceptive blind guilty quest to justify that false science, so that the suffering and the misery remained necessary.

This passage reminds me very strongly of the theories on states written by Peter Gelderloos in his book Worshipping Power, which I discussed a little in the previous post. For Gelderloos, empires are just one realisation of the general horror of states; his preferred distinction is between states and stateless people, not organised hierarchically and centrally. Gelderloos is highly dismissive of deterministic, materialist explanations for state development, whether the dubious geographical determinism of people like Jared Diamond, or the Marxist belief in class struggle as the determining factor of history. He writes:

Hundreds or even thousands of years of social evolution, along authoritarian or “homoarchic” lines, were required for the emergence of haves and have-nots, individual property, quantification of value, toilers and parasites. And parallel to these proto-state societies, we have examples of alternative forms of social evolution with an equal technological complexity and similar productive techniques, that chose decentralized forms of organization, and non- or even anti-authoritarian cultural values. As regards societies with little or no economic stratification, there are hundreds of examples of human societies practicing a variety of modes of production and different forms of political organization, from hunter-gatherers in California to agriculturalists in southwest Asia, with no clear pattern, no deterministic link between one and the other. Even among primates of the same species, practicing the exact same “mode of production,” one can find significant differences in the level of hierarchy between different groups.

Having argued aginst determinacy, and that the formation of state structures tends to precede rather than follow the stratification that Marxists placed as ontologically prior, Gelderloos offers his own interpretation. Over the course of the book, he describes a bewildering variety of paths to state-formation, usually generated ‘secondarily’ from the interaction of a state with a stateless people. How, then, to predict what course a society will follow? Gelderloo’s answer is to refer to a notion of ‘will’—individual intent and a collective ethos:

Turning material and other forms of determinism on their heads, Christopher Boehm, in an extensive survey of stateless societies, demonstrated that the key factor allowing a society to be stateless was not its mode of production or geographic conditions, but an ethical and political determination to prevent the emergence of hierarchy: what he referred to as “reverse dominance hierarchy,” in which special functions were compartmentalized rather than centralized and potential leaders were closely watched, and were abandoned, exiled, or assassinated if they exceeded their powers or acted in a greedy or authoritarian manner. In contrast to a mechanistic trend in academia that would dismiss freedom as a subjective illusion or meaningless concept, we anarchists assert that will, both individual and collective (at which level it is often read as culture), is an indispensable force for shaping our society, our mode of production, and our relationship to the earth.

The motor driving ‘will’

We should definitely accept these cautions—indeed, if one is a communist, one must accept the possibility of a dramatic transformation of the world we live in, and see it as fundamentally contingent, not inevitable. And I don’t particularly need to have faith in the supposed historical inevitability of the great revolution, especially given the track record of such predictions.

At the same time, to draw a line around ‘will’ and leave it unexplained feels like it is a bit of a cop-out. The things we want, that motivate us to act, cannot really be justified (beyond appealing to other, more ‘basic’ wants), but we can observe that they are not fully arbitrary either. After all, much of capitalism’s functioning, is conditioning us to buy what is being sold, go to work even when the boss isn’t there to force us… to play the game and express our desires in its terms.

Stereotypically dogmatic Marxists, of course, may reduce intention entirely to the supposed material ‘interests’ of a person’s class. To be sure, many allow a more subtle account, especially those who throw around words like ‘libinal economy’. Barhu, at least, is (naturally, given her experiences) able to see ‘will’ as something arising from ideology and history; she has seen first hand how Incrasticism is inculcated, and she sees her own desires (as we discussed last time!) as arising from the ‘engine’ of the world.

What of ‘collective will’? Something beyond individual people, evolving in many minds through constant conflict between all those who desire to shape it. We’ve seen that the Masquerade is held together by the spit and glue of blackmail, and that most of its powerful people would not even blink before sending their rivals to a miserable death. Yet “the Masquerade” functions, it can be seen as an actor; it is depressing to think that even those who oppose its project play a part in propagating it, wittingly or not.

To maintain a collective will, we circle back to the theme of control that runs throughout this series: all the schools for abducted, clinical courts and hygienic torture chambers; the ‘corrective’ rapes, operant conditioning, and delusions of eugenics. All of this is intended, in part, to maintain that ‘collective will’ of the empire, and make sure its subjects continue to act as if ‘the Masquerade’ exists. Whether because they believe in it, or because—like the prisoner who seems to escape, only for it to be a cruel illusion—they see no possibility of successful resistance.

This suggests, to me, that disrupting one part of Falcrest’s system—its economy—is not enough to kill the ‘will’ animating Falcrest, and transform whatever’s left of its people into ‘good neighbours’. But given that all these parts are not separate but interdependent, connected to each other through all these feedbacks… it’s not a separate goal either.

What would it take to force Falcrest to give up its imperial aspirations, short of a bigger fish showing up to colonise it in turn?

An aside on denazification

I realise that this is a problem that history has faced before. After the various capitalist powers (a term which I consider to include the USSR, with qualifiers) defeated Nazi Germany in the second world war, they faced the problem that much of the population of Germany had been thoroughly indoctrinated into the Nazis’ ideology, from childhood on up. The government was heavily bound up in the Nazi party and its apparatus. Somehow, they had to disillusion everyone of Nazism—and, not wanting a repeat of the end of the First World War, they did not seek to humiliate Germany with ‘reparations’, but rebuild it.

This is not a subject I’m all that intimately familiar with—my friend E_____, if she ends up reading this, may point to severe errors or oversights in the history.

Nevertheless, here is my understanding. Part of the project was to attempt to deny anyone ignorance of what the Nazis had done, by spreading images and video of the liberated death camps and concentration camps used in the Holocaust, and even forcing nearby civilians to help bury rotting corpses or exhume mass graves. Another part of the project was artistic: films in the decades after the war, such as Die Brücke (1959), attempted to deflate Hitler’s war mythology by portraying how it was used to send people to miserable, pathetic, meaningless deaths.

And of course, part of the goal was to get rid of all the Nazis in positions of power, and apply carceral punishment to those who had done the most horrific things. But it didn’t go as planned. Trying to assess an entire country’s population to determine who ought to be punished for supporting the Nazis proved bureaucratically impossible. The West German government ended up keeping many Nazi officials on in various capacities—sure, the ones running death camps went to Nuremberg, but many of the others got to continue much as they were. With the Cold War brewing, both the Americans and the Soviets needed their side of Germany to become economically functional, and keep general ‘good will’ to make sure the other did not seem more appealing. Bans on Nazi literature and art faced accusations that they were just doing the same as the Nazis. Even the Nuremberg trials were controversial.

The Americans were also, of course, extremely hypocritical in their treatment of Nazis. Figures such as Wernher von Braun, who had unambiguously used Jewish slave labour to build his rocket bombs, were extracted to America because their expertise was just too useful. The Soviets did much the same, both powers racing to collect German rocket scientists before the other guy.

Increasingly, and especially once the West German government took over from the American and British occupations, official denazification stopped, although Nazi symbolism remains banned to this day. In East Germany, meanwhile, the Soviet-backed government portrayed themselves as being much more sincerely anti-fascist, but then this was used to rhetorically justify the East German government’s own repressive measures like the Berlin Wall which had little to do with stopping any Nazis. And they weren’t above keeping useful Nazis around.

Of course, in the long run, Germany eventually became a capitalist state like so many others—quite an economically powerful one within the European Union. Like most countries in Europe, it has its problems with the current forms of fascism, and is invested in maintaining the brutal border regime that daily lets migrants drown. I can’t tell you that much about modern German politics.

My main point with this is—even in a situation where bigger fish absolutely did come in and win by military strength, transforming the ideology and social systems proved far easier said than done, and ultimately the victorious powers decided they had other plans.

Where’s all this going?

On this specific angle, I’m left with three questions:

- what’s Seth going to have happen in the next book?

- what do we think should happen in the next book? artistically, and by our understanding of this little world in a bottle

- what does Baru’s fictional struggle tell us about our own?

Of course, we’re not going to find the recipe for overthrowing capitalism for genuine communism in a fantasy novel. Still, novels help us frame questions—though as this book repeatedly points out, the person who frames the question has a great deal of power to shape its answer.

I genuinely don’t feel like I know if these books will end up in a victory, or a final tragedy—or whether I’ll agree with the presentation of whatever future Seth chooses! Though, more than any other fiction I’ve read in a long time, I feel like they grasp what’s at stake in this world.

Perhaps Baru’s trade venture will succeed beyond her dreams, and as such we will see her world end up on the same course as our own, with the national empires eventually giving way to an internationalised capitalism as the true power (the ‘divided god’ in the words of the Chǔang collective). Perhaps, with Oriati trim rather than Falcresti self-interest shaping the motives of this economy, trade will not come to rule over people; the Falcresti economic instruments will die off (‘wither away’ we might even say) with the state that spawned them, and the products of work will move according to need, coordinated by some other principle than profit. Though it’s hardly clear how this will happen.

And perhaps Baru and co. will find themselves needing to be overthrown as the power goes to her head. Perhaps Tain Shir will finally get to exact her revenge. (Actually that seems pretty plausible! That gun has spent a long time waiting to be fired.)

Of course, perhaps the possibilities raised by the lightning-soaked continent in the East of Baru’s world will throw a wrench in all of her plans, and something totally unpredictable will happen. I trust Seth enough to believe it will be well-founded in what has come so far.

But for all this to mean something beyond ‘that was a good fucking book’? Like Baru, all of us who read this are in positions where we’re deeply involved in a truly despicable system—and like Baru, we must play along for now, awaiting our opportunity to cause damage that matters and prove that their control over us wasn’t real. Like Baru, we must look to our own power—though collective power, rather than individual, holds more promise for most of us I suspect!

Much of Baru’s framing, of butchering an empire, is still relevant: we face the problem of ‘reconfiguring’ what can be salvaged of capitalism, and destroying what cannot. Whatever happens ‘next’, we must still eat.

When writing a pseudo-historical novel like this, there are some very difficult lines to walk. The miserableness of real history means it’s hard to reach for too happy an ending—nobody wants to be like “oh, oppressed people of the world, if you’d only done this, you could have killed the European empires and been free back in the 1700s”. I don’t think Baru is likely to do that, at all. But that leaves a different space: bittersweet endings, recognition of limits.

Of course, conversely, we also don’t want to shackle ourselves to history: by imagining what might have gone differently, in other circumstances, we keep open the imagined possibility that things will go differently the next time around. A ‘horizon of communism’.

I wish I could say, having considered all these angles, taught myself this history, I now have a clear insight into our real world, a tool to focus me. I do not have anything so definite… but I still appreciate the chance to consider.

Speculative speculation

Let’s imagine some ways Baru’s plan could go down, in a spectrum of outcomes…

She fucking dies

It could easily simply be that Baru tries to cheat death one too many times, somewhere along the way. She’s already risked sepsis and survived meningitis and has lobotomy picks inside her brain, not to mention all the people who are very keen to kill her. An unlikely outcome, since this is a novel, but within the fiction Baru has no guarantee that, say, Farrier’s secret contingency won’t blow her up, or she won’t catch a tropical disease on her voyages, or suffer whatever other nasty little fate. Or perhaps her bluff about the Brain’s rutterbook, which threatens the whole venture, could fail to be solved in time, so her first expedition runs out of supplies somewhere and everyone dies of thirst and scurvy. Or they piss off someone in Segu Mbo, or whoever’s on the far side. There’s a lot of ways she can die!

Assume, therefore, that Baru simply disappears; nobody knows what happened to her voyage. Her surviving friends, or perhaps one of the other Cryptarchs may take over her venture—if only to exploit it for some other scheme, since Baru is probably the only cryptarch who really believes in her trade venture right now. If Falcrest does manage to pull it off, they get stinking rich, and maybe Vultjag gets integrated into a new capitalist economy. ‘Total causal closure’ doesn’t happen because that’s just their ruling-class delusion, but they get plenty of chances to make peoples’ lives miserable… until eventually the long arc of everyday resistance manages to turn into a successful anticolonial rebellion.

In terms of making their rule permanent, it is unclear how effective Falcrest’s indoctrination apparatus has been in making their rule seem legitimate; the use of direct force is probably too fresh. But as we’ve seen, they’ve been doing a very effective job of wiping out prior modes of existence and integrating people into their economic system, so even if the centralised power bloc breaks, the ghost of Falcrest may take a long, long time to exorcise.

What else could check Falcrest’s growth? Baru’s trade circle is a lot smaller than our world; unlike the nations of Europe, Falcrest has no comparable colonialist powers to rival it. However, the Mbo could very easily go through a process of ‘late development’ in order to match Falcrest’s economic power, even without the Falcresti precipitating it, following the lines of the enclosures in our world; with vastly more natural resources, a ‘modernised’ Mbo which swallows some of Falcrest’s mythology could be a terrible thing (c.f. Imperial Germany or Japan for what happens when latecomers try to get into the colonialism game). Or even in advance of that, the Brain’s cult movement could precipitate the apocalyptic war she hopes for.

This is the default scenario; the question then is what difference Baru could potentially make?

It goes like real history

Baru kicks off her speculation bubble, and starts colonisation/trade efforts, but it doesn’t prove nearly as lucrative as she imagines, or at least the profits are slow to come through and people start to get doubts. The bubble collapses, and she is left bailing out a sinking ship as everyone wants out. An economic catastrophe, and maybe a speedbump in Falcrest’s self-reproduction, but if we know anything about capitalism is that it is surprisingly adept at moving its problems around to avoid breaking altogether.

Exactly how this plays out depends somewhat on the nitty gritty financial details. Unlike France and Britain, we haven’t heard tell of Falcrest being insolvent, and they already have fiat currency so unlike the bubbles we read about, there’s no question of uncertain transition from a gold standard. Like earlier speculative bubbles such as the tulip bubble, the frenzy for getting hold of Baru’s shares could go down as an embarassing episode of history, but not one that would destroy the host nation. In the Dutch case, the Dutch courts essentially voided many of the tulip-related futures contracts as being based on ‘gambling’, leaving people with their tulips.

Alternatively, it could go like more recent housing bubbles, and kick off an economic depression that requires significant action by the state to save the capitalist system. One thing I’m not sure about, and no doubt has many different people making all sorts of claims, is how far the collapse of the American housing bubble interfered with its ability to carry out its various foreign wars. The impression I have is that, even in a time of mass unemployment, America still pretty much issued a blank cheque to its military, then primarily occupying Iraq and Afghanistan. But I don’t know how to verify that.

There have been cases where economic failure has preceded total collapse of a state, but we’ll consider them shortly.

She gets caught

Let’s suppose, instead, that the first stage of Baru’s plan goes without major hitch: she sets up a vastly profitable trade route between Aurdwynn and the Black Tea Ocean, managed by Falcrest, and gets everyone to convert their money into shares in her enterprise. She embezzles money into the hands of her Oriati, Taranoki and Vultjag allies, letting them arm up and prepare, all the while publicly playing the part of the loyal Falcresti capitalist. Falcrest attempts to initiate its usual eugenic programs wherever it sets up its factors, but Baru is able to run enough interference to scupper these efforts.

But she’s hardly the only accountant/savant in Falcrest, so maybe someone will get wise to what she’s doing, and dob her in. It could end up being a much larger-scale version of her whole betrayal in Aurdwynn: the people moving to seize control of trade find lots of marines waiting. I don’t think the story is going to go there—it would be thematically inappropriate and deeply unsatisfying—but that’s another risk she’s playing.

In this case, Falcrest would be able to reap the benefits of Baru’s trade route, and spread incrasticism universally. Lots of colonialism, a heavy serving of genocide, we’ve seen what Falcrest do and they’d have no more reason to change. The only alternative would be the Brain’s apocalyptic war movement. There’s not much more to say about this.

But what if Baru ‘wins’?

Economic failure absolutely can lead to collapse of a political bloc, in the right context. The obvious modern example to me is the end of the Cold War.

The fall of the Soviet Union

In the latter half of the 20th century there were essentially two parallel economic systems, by which I mean like: networks of trade and resource distribution, moving around raw materials and manufactured goods, and methods for organising these things. These were centred on two blocs of political and military power in the US and USSR.

Well, you know the story probably. The Soviet one failed first, famously resulting in images of breadlines and empty shelves. It would be beyond the scope of this already-very-long post to go into different theories of the reasons for the USSR’s economic failure, and how much (if anything) it had to do with the work of their enemy superpower (e.g. through their losses in the proxy war in Afghanistan), but the USSR was in a period of ‘stagnation’, i.e. (recalling the previous article) the exponential growth of ‘the economy’ was slowing down. The leaders of the USSR attepted various measures to fix this economy, particularly through ‘liberalising’ measures, but perhaps because of relaxing suppressive apparatus, there were quickly widespread protest movements which, unlike the capitalist countries, the USSR was apparently not able to funnel away until it peters out in irrelevant demonstrations.

So the governments of the Soviet Union and its surrounding countries were taken out by a wave of revolutionary movements in which most of them fell. These are often painted as unusually ‘peaceful’, by the standards of revolutions; unlike the uprisings in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, the USSR did not (perhaps could not?) respond by suppressing the uprising with military force. Their state-centralised economic systems were replaced with more standard forms of private capitalism (where the state still guarantees property and contracts through its monopoly on violence, but only indirectly manipulates ‘the economy’ as a separate sphere, with minimal borrowing or welfare provision).

The shock of this change, and the disappearance of many of the state-run systems to provide housing etc. in favour of neoliberal reforms, led to a widespread collapse in living standards well beyond what was seen in the period of stagnation. The economies of many of the former Eastern Bloc companies collapsed, leading to millions of premature deaths and huge spikes in poverty and inequality; only a few ‘successfully’ managed to join the train of capitalist ‘development’, but most remain massively ‘set back’.

Moreover, the years after the collapse had to reckon with a lot of border-redrawing with attendant ethnonationalism. Sometimes this was beneficial: Germany, partitioned by a hard border, once again became unified, with the fall of the Berlin wall famously broadcast internationally. But as so many Soviet Republics became autonomous nation-states and softish internal borders became hard national borders, a whole fucking lot of ethnonationalist movements kicked off, leading in many cases to outright genocides such as in the Yugoslav wars.

Perhaps most relevant to Baru, the ruling ideology of Marxism-Leninism, which the Soviet state used to justify its existence, saw its power completely evaporate. It would generally be replaced with many of the usual machineries of liberal capitalism, with a mix of ‘centrist’ capitalist parties and ethnonationalists winning power in the aftermath. The new states would continue to operate prisons, police and armies, and run schools, but not pursue the exact same kinds of ideological indoctrination once attempted in the distant Stalin years. Of course, the new states would tell their own stories to legitimise themselves; I recall visiting the Estonian Museum of Occupations in Tallinn, which told a narrative of brutal occupation by first Nazis then even worse Soviets, ending in an exhibit celebrating its overthrow by the peaceful Singing Revolution. [Estonia is one of the post-Eastern Bloc countries that’s managed to recover better than most, though the ghost of that bloody past and strangely empty present still hangs over it—c.f. the mood of Disco Elysium…]

So how would this go in Falcrest, if Incrasticism fell from grace? Perhaps the true believers in eugenics would splinter into tiny sects and cults, while irridentist figureheads would try to gain power with promises to restore Falcrest to glory. Perhaps the former colonies of Falcrest would see bloody purges and contests for control, like the Kyprist-Canaat conflict in Tyrant. Meanwhile, as the upstart empire falls, the Mbo would become ascendant again—especially since Baru’s plan involves them gaining a lot of Falcresti wealth.

And what’s the long-term consequence? If we’re going by Soviet analogy, it may be a little early to tell, given it’s only thirty years ago that the USSR fell. Baru’s world is in a very different historical situation, with feudalism still ruling in most parts.

Let’s consider some practicalities instead. To guarantee profitable trade, she needs people to uphold property relations, which means ultimately, that her allies (those who hope to continue to profit off the trade route after Falcrest is cut out of the equation) must maintain the same monopoly on ‘legitimate’ violence that Falcrest once operated. After all, if one group can attack the trade posts and seize the wealth, who’s to stop another?

And that, of course, means that she needs to guarantee to the sailors plying her trade route that they won’t have their goods suddenly seized by rebel movements or pirates or such. Somehow, Baru needs to keep the ships sailing back and forth and profiting at her ports, even as the currency (Falcresti fiat notes) ceases to have backing (the ability to buy from the powerful Falcresti economy). The Brain was right to say she would, in effect, become a tyrant; instead of the favour of Falcrest, authority would now flow from proximity to Baru. Which is a rather alarming thought: Baru has resolutely opposed Incrasticism, but (despite Farrier’s best efforts), she’s a firm believer in Baru-knows-best-ism, and we’ve already seen what extreme lengths she’s prepared to go to in pursuit of her projects.

So effecting this transition would be the real kicker. Note from the historical anecdote we explored back in the second article that, when Vasco da Gama was bombarding Kozhikode to try and take over the Indian-Ocean spice trade, it completely froze trade on the Indian ocean for several months. Those months could spell famine in the places which have come to depend on Baru’s trade, such as the Llosydanes; perhaps Baru could secure some legitimacy by organising relief efforts.

Even with Falcrest’s economy gutted, it would hardly give up without a fight. Every rich bastard in the city would be clamouring to get their investment back in existential terror. The government’s big problem would be successfully mobilising a military force, when all its wealth is in the form of investment into Baru’s system. To take back its factories and trade posts, it would need to plausibly promise recompense to everyone involved in supplying their army.

Unfucking the financial system and getting the pieces moving again would take time; it might provoke infighting, given disagreement over how to take back their power. That time would give Baru’s allies a chance to create a defence, and unlike Falcrest, they would (if Baru plays her cards right) have plenty of wealth to feed and equip a fighting force. That’s the hope.

Supposing they succeed; what then? Baru would inherit a traumatised world, that’s just seen decades of hot and cold war, genocide, eugenics and other kinds of violence. Wherever Falcrest went, it’s been accompanied by plague and death. It’s disrupted the chain of reproduction of many social systems and traditions. That would continue to have consequences. People who had once lived people together as neighbours might form ethnonationalist movements and purge those they deem Other, like we’ve seen of the Canaat. Bloody revenge would be carried out on whoever had plausibly been associated with Falcrest.

Baru sees her trade route, and the foundation of a new economic system, as a way to thread the needle between Falcresti rule and total collapse. But given the way things have played out so far, it seems like it would be pretty miraculous for her to continue to hold things together, rather than to dissolve into what American counterinsurgency theorists term a situation of ‘competitive control’. Moreover, even if she was to succeed, she would face the usual problem of charismatic, unifying tyrants: creating a system of social reproduction which would outlive her, instead of seeing her empire dissolve in secession squabbles as quickly as it was built.

And what do we think, as anarchists? Is Baru’s failure what we want?

What’s scary in Baru’s plan to me is that there is little basis for an alternative way of life; Falcresti control would break down, but the structures which maintain it (or something like it) would have fertile ground to bounce back, because the people would see no alternative but rule-by-violence or death. But perhaps I have too little trust in people.

The Mbo, at least, remain robust and healthy despite the harms they took in the war; if Baru manages to avoid her trade system becoming a wedge of Incrastic values then it should survive the transition. Perhaps that, at least, gives room for some kind of non-Falcresti order to gradually form in the devastated places. Perhaps even in the years prior to her dramatic final coup, Baru’s interference as the person managing trade can help create room for pockets of an alternative world to survive and be born.

But that’s a lot to ask of one woman. It won’t all be down to Baru. After all, Baru’s eternal flaw is putting it all on herself. It seems unlikely that her current band of friends will let her forget to ask ‘what happens next?’, or that Baru’s conspiracy is the only real enemy Falcrest has. (This is always a limit of fiction; we can only consider what is portrayed on the pages.)

So Bryn, we’re up to the 10k word mark. Give us an answer—will it work?

Maybe. ;)

Ugh. Fine then. Should it work?

My hope is that whatever happens in Book 3, it will continue to surprise me. Cop-out answer, I know. But it’s the honest one: I think either a good or bad outcome could be made compelling.

Comments

Shard (3bafa8fb494ef34d5360e2ec1d38e2b4)

Isnt the point of Barhu’s plan precisely that Falcrest’s involvement in it is non-existent from the start? Its weird, because it suddenly seems to disappear when she finally explains it to the Brain, but isnt the entire point to use Falcrest’s wealth to create a trade route that would then facilitate commonly beneficial trade between the Mbo and the Stavky, bypassing Falcrest altogethet thanks to the never before possible route through the Imnarin and Voltjag?

In this setup, which is what she explains when figuring things out with her headmate, Baru seems to have a plan to trick Falcrest into thinking they’re doing their usual extractionist capitalist form of trade, when in reality she’d be setting up the rest of the Ashen Sea to cooperate to cut Falcrest out of world trade.

This is weird though, because that’s clearly her plan, and many other plots revolve around the northern side of that set up, but then when she talks to the Brain, and afterwards, its like they’ve forgotten that the trade is supposed to skip Falcrest altogether, almost like she’s hiding the full plan from The Brain and pretending to be reducing the whole thing to “Im taking over Falcresti trade” instead, when the real plan should be much easier to “sell” to the Brain.

The real plan of course seems to rely a lot on “hopefully people will do good if given the chance, and creating this trade route allows for material wealth to move between the Mbo and Stackiavhi Necessity, and once Falcrest has been removed, hopefully people will thrive because there aren’t other Empires around”. The vibe I got through the book at first was that Baru had understood that a good world is made by cooperation between people, by people being good to each other, and that a single person scheming couldnt create that world, so she needed to, instead, focus on creating the conditions that would make such a world possible, knowing that after that, it’s on the rest of the world to cooperate; so she comes up with the best conditions she can think of: a trade route that connects vastly different places and would allow everyone involved to thrive, because trade does not have to be a zero sum game.