originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/616464...

This is largely a synthesis of thoughts I’ve expressed previously. The first part is a summary of how action games model the world, the second part some speculation as to how they could be extended into new kinds of game…

If you punch someone, the momentum and energy of your fist is absorbed by their body’s tissues. Depending on where and how you hit them, they might get a bruise or cut, or break bones, or suffer a lasting head injury. Whatever happens depends on physics and the material properties of the human body.

This is not, by and large, how videogames work. For one, soft body damage is way too computationally expensive to simulate in real time, and for another, it’s extremely difficult to offer a control scheme that gives you a reasonable handle on a fighting character in a full physical simulation (the few games that try are mostly comedy games, with the only exception of Exanima, which remains basically a tech demo). To the extent that physics sims are used, it’s to show characters losing control of their body and collapsing, and this is animated based on a rigid skeleton (ragdoll physics).

So how do action games, which aim to portray a bunch of people running around and hitting each other, and give the player a feeling of control and power, model this?

With very few exceptions, everyone in an action game (or indeed most kinds of game) is a state machine. A character may be in dozens or hundreds of states, depending on how they are moving and acting.

To communicate this information to the player, developers produce a variety of short snippets of animation corresponding to different states a character may be in: running in different directions, different stages of a jump, many different attacks, taking a minor injury… Usually in modern games there is a degree of procedural animation blending: a ‘running’ animation that affects the legs and a ‘swinging your sword’ animation that affects the arms.

State transitions and cancelling

Depending on the overall game state, characters might then end up transitioning from one state to another: a character stops running and goes from their run to their idle animation; a player presses the second button in a string at the right moment and the animation of that string continues, or misses the input and the character returns to their idle animation; a character is hit by an attack and goes into their ‘being injured’ state.

Each state transition also needs an animation (because anticipation and follow-through are vital for ‘selling’ an animation). A character who stops running will slow to a halt over a few steps instead of abruptly snapping to the ‘idle’ position. Since the number of possible state transitions is enormous, usually a lot of them will be handled procedurally; over a short period the character’s skeleton will ‘blend’ (e.g. through linear interpolation or lerp) from one animation to another. (Alternatively, the animation system can let go of the character and hand them over to a ragdoll solver to have the character fall from whatever position they’re in.)

This video has some pretty good examples of animation transitions for the sake of anticipation:

Each transition is effectively another state for the state machine. You might have something like

(running forwards state) → [player releases ‘run’ button] → (slowing down state) → (standing state)

with further fine-tuning depending on how complex the animation system is.

Some transitions may be permitted at a particular time, and others might not. Deliberately transitioning from one state to another, interrupting the animation, is referred to as ‘cancelling’ an animation by fighting game players. For example, you might say a particular attack animation can be ‘cancelled into’ a block or a dodge or a different attack after a certain point, if the button is pressed at exactly the right time.

If an animation is not cancelled or otherwise interrupted, after it completes it will probably have a default state transition (e.g. restart a run cycle after each step, or go to the idle state after finishing an attack).

For animations that are important game mechanically, there will usually be a period during which it can’t be cancelled by the controlling player: the player is locked into committing to a particular attack or using an item animation once they hit the button. This creates a risk/reward mechanic: a more powerful attack might take longer before it can be cancelled. The Dark Souls and Monster Hunter series for example are known for having long attack animations which can’t be cancelled by the player for a longer time than in many games, so the player must take care to position themselves safely before taking the risk of attacking.

Anatomy of an attack

In action games, the main means of interaction is attacking enemies and avoiding their attacks.

If an attack hits, it typically does a few things. Most of the time, injuries are tracked with a hit point system where each character has an associated number, which is depleted a certain amount when they’re successfully hit by an attack. In addition, getting hit usually triggers a state transition on the character. This is partly to ‘sell’ the hit (a term from professional wrestling, which faces a very similar set of concerns): an attack should leave enemies staggering in order to feel powerful.

It’s also a game mechanic: many action games have ‘hitstun’ where a character who is hit may have their attack animation interrupted (perhaps depending on some combination of factors).

Animation generally requires a few frames of anticipation (again part of selling the hit); after this, there will be a segment of animation in which one character can register a hit against the other. Whether they do is determined by collision detection.

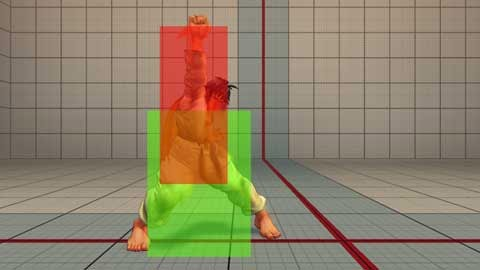

For efficiency, collision detection in this case is usually handled by testing for intersection between squares and cuboids. The attacking character has one or more ‘hit boxes’ around the parts of their model which are considered potentially damaging (a fist or the blade of a sword); the receiving character has ‘hurt boxes’ around the parts of their model which can receive an injury. If the hit box overlaps a hurt box at any point during this part of the animation, the attack hits and triggers its various effects.

For this reason, the time between a player pressing a button indicating their intent to attack, and the hit box first appearing, is very important in fighting games and action games. A fast attack is one which ‘comes out’ (manifests a hit box) sooner. Such an attack has ‘frame advantage’ over an attack which comes out slower. If two attacks are input at exactly the same time, the attack with frame advantage will hit first, and may interrupt the slower attack. This is a simple but powerful risk/reward mechanic.

Following the frames with a hit box, there are a certain number of frames of follow-through during which there is no hitbox, but the animation can’t yet be cancelled. These are typically called the attack’s ‘recovery’.

For certain games, finding unusual (and perhaps unintended) ways to cancel animations early allows the player to do creative things. For example, in NieR Automata, it’s possible for the player to self destruct, which requires holding an input for a few seconds. This can be begun from almost any animation, interrupting that animation. So ‘self-destruct cancelling’ by very briefly tapping the self-destruct input, but not completing it, allows certain combos to be achieved which couldn’t otherwise.

Strings and combo systems

A totally basic action game could have one attack animation, which can be cancelled into the same animation. Or perhaps they might have a variety of attacks, which can be cancelled into each other.

Often, however, games change the available attacks based on the character’s current state. For a simple example, starting from standing, a character might swing their sword from left to right; if the attack is input again, they will swing their sword from right to left. Should the player keep pressing the button, there might be a programmed sequence of swings with unique animations, which will feel a lot better and more varied.

Such a specific preprogrammed string (if properly executed) may lead to attacks with special effects (a wide area of effect attack, an attack that inflicts a certain status effect, or an attack that knocks enemies into the air). For some games, like Bayonetta, just about any combinatorial string of attacks has its own sequence of animations and effects.

In fighting game terminology, a string is a particular series of attacks (often, attacks that happen faster when done in that sequence); a combo is a sequence of attacks which keep the enemy stunlocked, not allowing them to act or retaliate. Fighting game designers may give certain characters the ability to inflict a deliberate finite combo; if the opponent fails to block or dodge the first attack in the combo, then the attacking player can inflict a lot more damage by correctly executing the rest of it.

In other action games, the terminology is looser, and a combo can sometimes refer to a string which doesn’t necessarily keep an enemy stunned; in these contexts people might refer to a true combo which does keep the enemy stunned. Certain games, usually called character action games, have a particularly rich system of attack strings (combos in the loose sense) which lead to people making combo videos where they create particularly stylish sequences of moves which keep an enemy stunned or ‘juggled’ (floating in the air). Here’s a modern example by donguri990 for Devil May Cry 3 to 5:

In each segment, donguri uses attacks which sustain the enemy in a stunned or ‘juggled’ state. It is difficult to perform a perpetual juggle because by default an attack string will include a long enough pause for the enemy to get back up and attack again; a long combo thus requires knowledge of ‘tech’ for cancelling animations early and creating unusual state transitions; on top of that there’s all the elements of style (using varied attacks, timing it to music etc.)

Designing games with all this in mind (in existing genres)

Some games are derided for shallow combat; others are praised for particularly ‘deep’ combat systems. What’s the difference?

This is necessarily subjective, and different games pursue ‘depth’ in different ways. In a game like Dark Souls, the emphasis is on avoiding enemy attacks, and you usually only have a couple of attack strings; in a game like Bayonetta the emphasis is on styling on the enemies and so the game needs a lot more complexity.

A complaint with some games is that you can get through the entire game just by using one simple strategy, rather than having to adapt to enemies, or that you can ‘button mash’ without any actual understanding even if the potential for depth exists. (This accusation has been levelled at NieR Automata for example, which only really requires you to understand the combat system in depth in the siloed off dlc arena). This is a tricky bind: make the game too hard and demand too much precise understanding and execution, and you exclude a lot of players.

Some of this can be solved by having difficulty controls, but you have to get around the general cultural feeling that playing on ‘easy’ makes you lesser somehow. (One thing you don’t want to do is automatically adjust the difficulty or badger the player to do so, since that tends to feel insulting, and for many players - like me - pushing through the difficulty is one of the reasons to play the game.)

Score systems as seen in many character action games seem like a fairly good way around this: you can mash through for a low score, but you get a special pat on the back for a high score (playing for which is, if you’ve designed your game well, intrinsically rewarding.)

Anyway, that concern aside, what makes for a deep combat system? It’s not simply having a lot of animations, if they’re all functionally the same. I guess it’s something that 1. requires you to pay attention and 2. has a lot of variety. Games are almost always designed to have a careful difficulty curve which gradually teaches the player more complexity.

You can put that complexity in different places. One part of the game can be repetitive (a weapon’s attack string for example) but the varying context puts pressure on you that makes it harder (e.g. while learning the attacks of a series of different bosses in a Souls game). This is taken to extremes by WoW-style MMOs, which typically have each player executing a fixed ‘rotation’ of abilities (or applying a priority system), and the challenge comes from maintaining that rotation while simultaneously processing a boss’s mechanics (requiring tight choreography in a group).

(MMOs tend to make the state transitions much more explicit in terms of labelled ‘buffs’ and ‘debuffs’ on a character; their animation systems are often less complex and enemies rarely sell hits, since they are being simultaneously hit by a large group of players. Instead the weight of a hit is conveyed by particle effects and sound design.)

On the other hand, in Bayonetta, outside of bosses the enemies generally aren’t very memorable; the fun comes from exploring the space of the combat system and playing for score. (Though later in the game, once you’ve had time to practice, enemies start hitting harder and it becomes more important to avoid their attacks.) Bayonetta gives you most of its combo system right at the start (though you unlock more with new weapons), but you can pick it up at your own pace (or stick to a single combo).

In Sekiro, almost all the emphasis is on very precisely timed responses to parry enemy attacks, with the result that the game has often been called a rhythm game. The variety comes from the variety of enemies and attack types.

If you have a complex combat system, one thing you don’t want is to force the player into one specific technique, because it’s much more effective than all the others. NieR Gestalt has an incredible story, but the combat falls down: though there are a variety of weapons and attacks, it’s easy to get interrupted and knocked down. In the end I came to rely on a ‘stinger’ attack (a term from DMC referring to a short dash to hit a nearby enemy) which came out very quickly and stunned enemies around you. This got quite noticeable in my stream of the game because there was one specific grunt sound attack associated with this attack, so it was a lot of ‘hyurgh! hyurgh! hyurgh!’.

Part of the problem in a combo system is helping the player remember all their options in a given state fast enough to make a meaningful decision as to what to do next. Monster Hunter World helpfully shows the available buttons in a state on the top right of the screen, which helps a lot in picking up the combos for a weapon. By contrast, I found it almost impossible to get the hang of combos in Warframe’s previous combo system, since there was very little feedback to tell if I was doing the pauses right. (The recent update has made it a lot easier!)

I’m sure my friends who play more action games could furnish other examples to fill out the space. There does seem to be a ceiling on complexity: there are few games with the enemy complexity of a Monster Hunter or Dark Souls and the combo depth of DMC or Bayonetta. It’s just too much to keep track of; Monster Hunter fights already feel extremely chaotic!

Do we have to fight?

Action games have built up a really interesting set of mechanics in my opinion around the abstractions and animation systems that the computer affords. So far, these have almost exclusively been used to represent fighting.

What about dancing? I have previously called MMO raids a kind of dance, and the same might go for a combo video. But narratively, they’re still fights. Is there a way we can draw on this library of concepts - state transitions, animation cancels, combos - and put it into another fictional domain?

There are dancing games, but they tend to be more ‘simon says’ type rhythm games: you are instructed to perform a series of moves at the right timing, often using peripherals like the Kinect. An amusing example is Kinect Star Wars: Galactic Dance-Off:

Another more recent example in is the incredible cabaret dance sequence in Final Fantasy 7 Remake:

There are also a variety of VR rhythm games such as Beat Saber.

Still, mechanically these are ‘just’ rhythm games, i.e. a series of QTEs; you pay attention to fixed prompts and hit a fixed series of buttons (or perform actual dance moves in front of a camera!) at the right time or you get a worse outcome. Could we make a truly expressive dance animation system where you get to choose what you do to create dances the developers never envisioned?

Some exploration in this area has already been done in the form of skateboarding games, which rely on a very similar animation system to action games. While a character in an action game might have states like ‘swinging a sword’ and ‘recovering from an attack’, a skateboarder might have states like ‘preparing to jump’ or ‘grinding on a rail’, which, just like in an action game, determine the available moves. Rather than taking a hit from an enemy, you can hit a wall at the wrong angle and fall off your skateboard. (Warframe managed to include both skateboarding and fighting in the same game, though the skateboarding minigame is pretty peripheral to the whole thing.)

I’m sadly much much less familiar with skateboarding games as a genre, which is a shame because they seem to be all about just playing for pure expression (loosely measured by a scoring system which encourages you to mix things up and try different moves).

You could imagine a dancing model where your character performs dance moves as you press buttons. But there’s not really a challenge to this yet. Challenge in skateboarding games comes in part from moving accurately through 3D space, landing where you intend to, and pulling off moves in the window between jumping and landing. So what sort of challenge do we have in hypothetical dancing game?

One natural answer might be to combine the rhythm game and action game elements: you still need to tap on the beat, but rather than having to tap specific inputs, you have a choice. You could also add a positioning element - indeed, make it multiplayer and allow players to set their own positioning prompts to create a group dance? (Or else, allow a player to record a performance for each dancer in multiple ‘passes’… at this point we’re just creating a film animation system!)

I keep thinking about this concept (I doubt this is the first time I’ve posted about it) but I still haven’t figured it out. Perhaps what I should do is start experimenting with creating such a game myself, and see what shows up…

Another route: movement games

Games where the challenge is movement are already well established in the form of platformers. A major challenge in such games is making the motion intelligible to the player at a fast enough speed that they can direct it. This leads to the result that typically motion in cutscenes is often much more quick and fluid than what the game affords.

(Some games, like the Assassin’s Creed series, abstract the details of motion away entirely and allow the player to climb walls simply by pushing the stick in the vague direction of a handhold. There’s a lot of clever animation work going on ‘under the hood’ in such games, but I have more fun with parkour games like Mirror’s Edge which invite you to press buttons to indicate the particular movements you want…)

One thing I’ve been thinking about is how you’d try to make my story VECTOR into an action game. In my imagination, you’d move like a dragoon in the last couple of minutes of the FFXIV Heavensward trailer, or Ahsoka’s jumping off spaceships in a recent The Clone Wars episode: dash in, attack, dash away. But having the camera keep up, and indicating where you want to go, sounds extremely challenging.

Drag-on Dragoon 3, though by no means a particularly deep character action game, did at least do something cool in its ‘intoner mode’, allowing you to rapidly close the gap with an enemy mid-combo. But though it’s very satisfying, it is pretty much button mashing…

There’s a promising direction in the 2D metroidvania-ish game Dandara, in which you indicate the direction you want to move and leap to the opposite wall ignoring gravity, but this would be a great deal harder to implement with more degrees of freedom. (Dandara is already far from an easy game…)

One of the closest games I can think of is the Tribes series; what was originally a bug which allowed players to slide over the ground at high speeds became the central feature of the series, in which players slide around making short jetpack hops while firing slow rockets at each other. It’s a game of leading targets and moving at speed and it’s immensely satisfying to come in like a bullet and grab a flag and leave before anyone can even react to your presence. (Sadly, the most recent game in the series, Tribes Ascend, died some years ago, and there do not seem to be any more coming.)

Anyway this is sort of off the main thread of action game mechanics, but part of what I have been wondering with this very rough concept is how you’d fit in these action game mechanics in something where you’re moving very fast. Possibly a kind of bullet time option so that when you get near an enemy you have time to execute a combo/dodge some attacks? And then maybe a way to play the whole scene back at full speed afterwards?

One of the key techniques in DMC combos is to jump off enemies in midair to reset your air attacks and sustain your juggle. Perhaps certain attacks could both damage enemies and redirect you; the game is one of moving rapidly from enemy to enemy for very quick engagements, bouncing off walls and maintaining a constant flow of motion like in a skateboarding game?

All this remains rather hypothetical for now since my game programming and animation skills, not to mention the amount of time I have, are not remotely up to the task of creating such a game.

Comments