originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/754857...

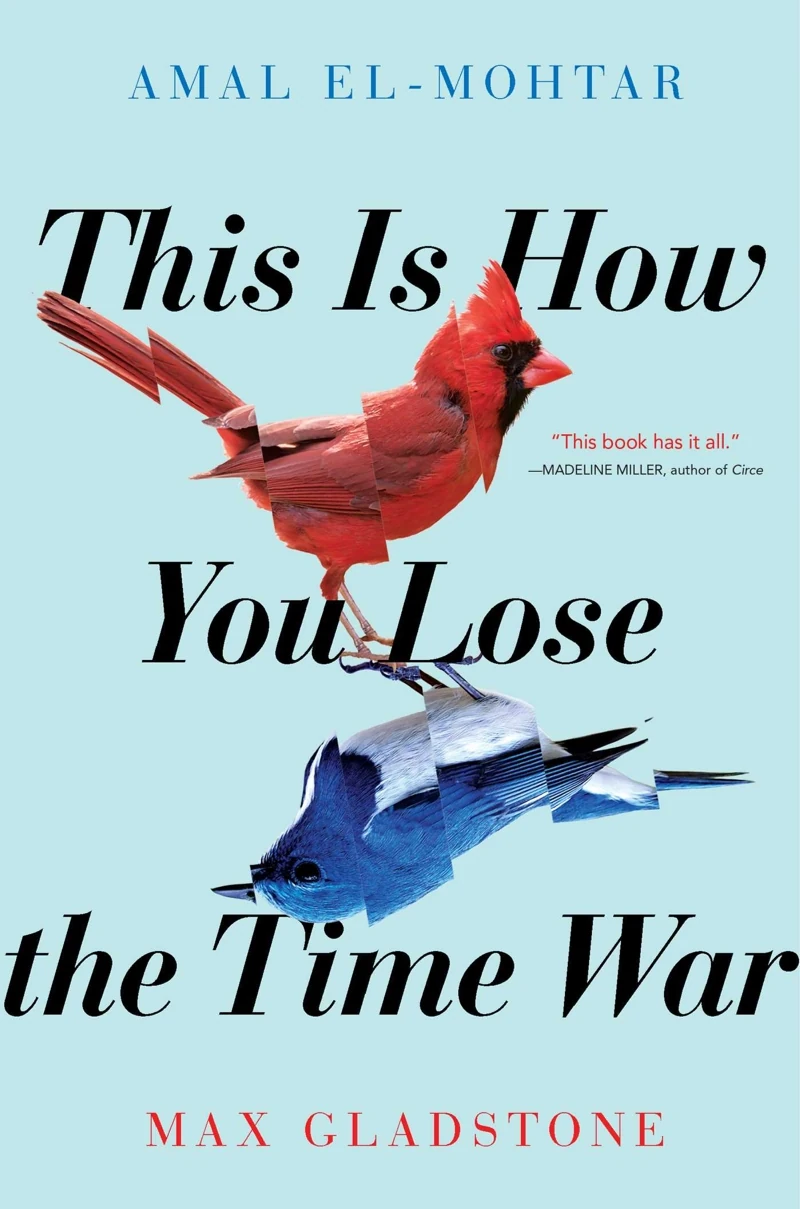

as mentioned a little earlier, today I read This Is How You Lose The Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone…!

Before we dive into the spoilers, a brief word about what this book is…

TIHYLTW is a semi-epistolary novel about time travellers Red and Blue and, essentially, their enemies-to-lovers romance as they play spy games across the broad, branching timeline, acting respectively on behalf of the ultra-high-tech ‘Agency’ and the biopunk ‘Garden’. Each chapter consists of a brief vignette depicting one or the other at their work, ending with the discovery of a letter (in some abstract, poetic form like a dead fish) from their counterpart, followed by the contents of that letter.

A lot of the structure of this book is explained by the knowledge that this was written as a kind of chain-writing project: El-Mohtar and Gladstone hashed out the broad premise but then alternated writing the chapters, with Gladstone taking on the role of Red and El-Mohtar as Blue. Each would respond to the other’s letter and advance the story a little bit. In essence, then, this is also something like a play-by-post roleplaying game. I have played both chain-writing games and play-by-post roleplaying so this all ends up feeling quite familiar.

What’s remarkable, given that approach, is that this book manages to maintain a generally consistent voice and clear narrative progression. But knowing how it’s written still gives you some insight, because you can read it in the light of improv comedy. For example, when Red describes Blue’s world, so far undefined, as ‘viney-hivey elfworlds’, this is what in improv terms we call an offer: you define something and hand it off to the other person to iterate or play on it somehow. In this case, El-Mohtar has Blue gently rebuff this as ‘full of silly stereotypes’ and ask for a more genuine reply about her own life (this is early in the romance, where they are expressing mutual curiosity which also serves as exposition); Gladstone can oblige and give us Red’s backstory.

In some cases, the fingerprint of chainwriting is very obvious. One chapter has Blue sign off ‘see you in London next’ - Gladstone responds to this by setting the next chapter in an alternate-world city called ‘London Next’, ‘the kind of London other Londons dream’. This wordplay, reinterpreting the last entry in an unexpected light, is such a blatant chainwriting move.

Two writers who vibe, with a back-and-forth, is probably about the ideal scale for this kind of game. At university I played chain-writing games in a large group, where each player got to contribute only one section to the story; this too often became a ‘too many cooks’ situation, whose pacing would suffer from the lack of larger structure. As a player in that kind of game, you’d have to balance leaving your own fingerprint by adding elements to the story, and advancing what had already been written (I very much tended to the former). Too often it would fall to the last person in the chain to try and hastily tie the story up in some sort of resolution.

Play-by-post roleplaying games don’t have that ‘one entry per player’ limit, but the problems of time zones/availability and the general principle to not ‘godmod’ meant that often the game would either die pretty quickly or turn into a situation where each person was essentially writing their own story in isolation, with minimal interaction with others. Which can be fun: a collection of web serials on a theme is a perfectly valid writing project. But it’s not really a collab in this way.

A project limited to just two writers, on the other hand, can build up a rhythm, and this is what happens here. A lot of the charm of this novel is the playfulness of the back and forth, not just in the letters themselves, but also in the settings introduced and gradual expansion and iteration of the concepts. This feels like it would be a tremendously fun game to play (ehem).

Now, let’s apply the Spoiler Zip, and talk about some details.

So this is essentially a spy story; it is a story of the two characters, both prodigy agents, mutually defecting from the Time War to elope together. Though there’s plenty of drama when they get found out, death fakeouts, a kind of classic gay personality synthesis…

Most of the chapters end with a ‘Seeker’ appearing to swallow up the remnants of the letter that has been read. With ‘hunger’ becoming a symbol of the relationship in the letters, and the time travel theme, I guessed that this character would somehow represent a synthesis of the two characters retracing their relationship. Well, almost!

Broadly, the dénouement is: Blue strikes a (rather vaguely defined) decisive move in the Time War, but Red’s superiors figure out some of the situation and set her up to entrap Blue; Red appears to have killed her (with a letter naturally), but she goes rogue and attempts to assimilate enough of Blue’s being (through the letters) to enter the Garden and innoculate her against the poison at birth, thus allowing Blue to turn out to be alive and save Red from space prison. So it’s not quite another 2010s SFF story in which a lesbian carries the ghost of her dead girlfriend in her head but… it sorta is, innit.

As might be evident from that paragraph, the time travel model in this story is definitely of the ‘timey-wimey’ variety. It’s not really about that; the logic is much more poetic than it is, well, logical. Characters move very freely ‘upthread’ (towards the distant past) and ‘downthread’ (towards the scifi future). Their adventures tend to take them to fairly recognisable bits of history, with a reasonable sprinkling of mythology.

What they’re actually doing in these places is broadly speaking similar to the card game Chrononauts if you’ve ever played that, attempting to shape the futures by changing the past, but generally speaking in subtle ways - we’re given various examples of saving crucial people from disasters, inspiring inventions, and so on. Of course, they must have a reason for this subtle approach: in this case, ‘chaos’ is anathema to both sides.

Our characters, as superspies constantly assuming different identities and assassinating people and all sorts of other things, are pretty disconnected from the people whose lives they mess with - something that becomes more explicit later, with the remark that the work involves, often, killing and saving the same people in different timelines. As such, there are few particularly well-defined characters in the story besides Red and Blue - the only real exception being Red’s scary, nameless Commandant. Now and then we’ll get the allusion to a historical figure, such as Genghis Khan, but only rarely. These bitches have eyes only for each other. Their interactions are frequently compared to a game (mostly go, sometimes a little chess), and the places they pass through are relevant largely insofar as they constitute moves in the game.

This is where I think the comparison to Italo Calvino that I made earlier breaks down. Here, the setting is in large part colour: material for the playful romantic interactions of our two spies. There are definitely some imaginative setpieces - I liked the computer cult of Hack, and the prehistoric valley of bones - but in contrast to Invisible Cities where the relationship between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan is a frame story and the vignettes about cities are the main focus, here the balance is opposite.

On that front of setting, I think I found the factions themselves a little insubstantial. Of course, the point of the novel is in large part that their differences are generally superficial and should be transcended - but beyond that their natures are fundamentally opposed, we never get a huge sense of why the Agency and Garden are battling over the timelines. One is plant themed, the other is robot themed. One plays the long game, the other likes finesse. But both Blue and Red are in some major way alienated from their society - indeed, Red even suggests this is the major qualification for becoming a time agent in her society. They fight the Time War because… they were constructed to do it, because it’s a relief from existential despair, and later, because it’s sexy to fight a Time War with someone?

If interpreted as an enemies to lovers arc, well, it’s not really that. More of a strangers to lovers arc; there is little to not antagonism outside of the occasional bravado about who will win the game. They’re really the ultimate u-haul lesbians. But perhaps that’s putting a foreign frame on it. ‘Courtship through scifi strategy duel leading to transformation through synthesis’ is literally a premise I wrote too, I can’t possibly complain about it!

I refuse to add another ‘lyrical’ to the pile, but I can’t deny the craft on display here. Still, sometimes the allusions feel a bit too ‘local’ to my time and place to belong to truly alien beings. Sometimes this is lampshaded - for example, in the first letter from Blue, Ozymandias is quoted, but immediately described as an ‘overanthologised work of the early Strand 6 nineteenth century’. That sets up a callback later in one of Red’s letter. Another time, Blue recommends Red a fantasy novel written in the 50s, remarking that it is (somehow) the same in every timeline it appears. It’s tricky to know how to call this - if the allusions were made up or too obscure, you’d lose the playful way in which they are invoked, yet having a strange transhuman future creature throw out references that feel like they belong to a 20th century university student feels like it familiarises a little too much.

Some of the wordplay also feels… how to put this. The example I’m thinking of is that the characters start riffing on a 19th century etiquette book to help Red get the hang of letter-writing, and this makes reference to a scented seal (wax thing that is used to close an envelope). So Red embeds her next letter inside a seal (marine mammal). My natural assumption is that the characters are speaking $mysterious_future_language, but this kind of pun makes it impossible to read them as speaking anything other than English, right?

But that’s the tone of this novel. It’s constantly teasing. The Utena influence (I’m told Gladstone is a fan) is certainly strong.

There is something, too, to the way that Red’s arc is to step away from the cyborg state where all her inconvenient organs and biological needs can be shut off, and expose herself to what we could call more human experiences - hunger, crying. This is clearly deliberate and rich in metaphorical valence (she is becoming more akin to Blue, and more distant from her utilitarian origin), but she’s also coming towards us. This isn’t a flaw in the novel, but more a limitation of the medium: we can only see through our own experiences, and thus to write a comprehensible emotional arc for an alien being, we must build our own ‘bridges’ (to use the novel’s metaphor, see what I did there you fuckers) to their experience, and make them more human…

Taken as a spy story, I think the issue is perhaps that the characters are too important. Far from cogs in a vast, grinding geopolitical machine, it feels like Red and Blue are the most important people in all the universes, the only players that matter on either side. Their courtship is inevitable - they just don’t need all these other chumps, who can’t see how sexy it is to write emotional letters to your rival spy. Everyone else is basically an NPC.

As much as I rib it though, this was basically the perfect train book, and made that five hour journey pass in a breeze. I don’t know that I’d really put it on Calvino tier, but I’d still definitely recommend giving it a read, it’s a good playful book about lesbians doing a hilariously overcomplicated courtship and what’s not to love about that.

As a final addendum - I’ve been gently reminded that El-Mohtar is ‘the prototypical bi woman married to a man who goes to great pains to constantly remind everyone she’s not straight’, which, you know, fair enough lmao. If my bi granny hadn’t married a guy (eight years her senior, no it did not go well), then I wouldn’t exist! I just think it’s kind of funny.

(and ftr? I don’t actually give a shit whether the people who write a book belong to the ‘right’ identity category. On the contrary, I think everyone should write a gay romance at least once, it’s good for the soul, maybe you’ll realise you like it more than you thought you would, eh~)

Comments