originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/698652...

Hi friends, it’s Animation Night.

Tonight we have the exciting occasion of: finally hitting another power of 2! A phenomenon not seen since Animation Night 64, when we watched Macross. Who knows if we’ll ever see another! I’m going to have to fill another 128 nights, and while we’re still not out of material, that’s a lot of nights…

Since powers of 2 are especially computer-y, it only seems fitting that we focus on the subject of computers. So let’s roll back the clock and have a look at some representations of ~the digital world~ in animation!

So, computers. I’ve already done the early history of 3D CGI animation back on Animation Night 75, which means we’re gonna take a slightly different tack on this one.

In less than a century, computers have been introduced to the world and integrated themselves so universally it’s hard to imagine life without them. Even as recently as the 80s, when they got small enough to have one in your house, these computers were still pretty novel.

And how do humans deal with a strange new technology that defies comprehension in terms of the familiar? Well, we anthropomorphise it! So that has led to the curious little genre of stories set ‘inside’ a computer system, imagining as comprising a little world where programs are little people…

TRON (1982)

Let’s start with the film Tron (1982). No, just one ‘o’, not the weird pejorative for a trans somethingawful user.

Tron is… well, really the main reason it’s remembered is the technical side so let’s dive right in. Primarily a composite of live action and extremely complex rotoscoped backlight animation, this film also features some of the earliest CGI sequences in film. But it’s also a narrative about computers, imagining a computer program hero fighting in the world implied by the vector-display games of the era. But I’m mostly going to talk about how it’s made because it’s one of those ‘once in film history’ type of productions, similar to A Scanner Darkly (Animation Night 120), which proved so ludicrously labour-intensive that nobody felt like doing it again. Let’s dig in…

The impetus came when a guy called Steven Lisberger saw video of Pong (the game) in 1976, which led him down a path to take an interest in this new-fangled computer animation being toyed with at MIT. Lisberger was a big tech enthusiast, and hoped to bring the idea of computers to a wider audience beyond its ‘clique-like’ users at the time. The concept of a hero throwing discs was one of the earliest elements, used by Lisberger to promote his studio; the rest of the script built around it.

The film was originally planned to just use traditional animation. News of the project caught the attention of computer scientist Alan Kay, who became technical advisor for a set of CG sequences - not to mention the inspiration for the film’s scientist character. Gradually, the concept evolved from animation, to animation bracketed by live action, to finally live action composited into animated scenes.

Lisberger’s growing gang shopped around for a studio willing to take on such a complex project; eventually they found Disney, who funded a test reel to try out the new techniques - mixing live action, backlight and CG. Despite funding the film, Disney’s insular animation department were unwilling to get involved in animation on behalf of an outsider, so the 2D animation went to Taiwanese studio Wang Film Productions, an outsourcing oriented studio that took on vast amounts of work from Western companies like Disney and Hanna-Barbera. The CG, meanwhile, went to the tiny CG graphics industry; Wikipedia writes:

Disney turned to the four leading computer graphics firms of the day: Information International, Inc. of Culver City, California, who owned the Super Foonly F-1 (the fastest PDP-10 ever made and the only one of its kind); MAGI of Elmsford, New York; Robert Abel and Associates of California; and Digital Effects of New York City.[7]Bill Kovacs worked on the film while working for Robert Abel before going on to found Wavefront Technologies. The work was not a collaboration, resulting in very different styles used by the firms.

This was a time when a production computer in the film industry might have as little as 2MB RAM. To handle this, they’d use some of the same techniques as PS2 era games, such as aggressive fog effects. And there was no digital compositing or even just printing onto film: to get CG onto film, they would render a frame, point a camera at it, and take a photo as in stop motion animation. Crazy shit.

Alongside this was an equally elaborate effort to produce all the backlight effects for all the glowing lines. This involved an absolute ton of manually-painted traveling mattes, with a dozen or more passes to expose each coloured glowing element photographed in sequence onto the film. There’s very little traditional animation so much as very elaborate rotoscoping, but it was an astonishing work of compositing. Here, I’ll let Wikipedia explain what they did…

In this process, live-action scenes inside the computer world were filmed in black-and-white on an entirely black set, placed in an enlarger for blow-ups and transferred to large format Kodalith high-contrast film. These negatives were then used to make Kodalith sheets with a reverse (positive) image. Clear cels were laid over each sheet and all portions of the figure except the areas that were exposed for the later camera passes were manually blacked out. Next the Kodalith sheets and cel overlays were placed over a light box while a VistaVision camera mounted above it made separate passes and different color filters. A typical shot normally required 12 passes, but some sequences, like the interior of the electronic tank, could need as many as 50 passes. About 300 matte paintings were made for the film, each photographed onto a large piece of Ektachrome film before colors were added by gelatin filters in a similar procedure as in the Kodaliths. The mattes, rotoscopic and CGI were then combined and composed together to give them a “technological” appearance.[16][24]

The result is honestly… kind of weird looking; the actors are all very monochrome, and the CG shots lack the grain and atmospheric glows of the intercut live action shots. As animation, it’s kind of stop-start and since every shot was so expensive, they tend to go by very fast. But that only makes it more interesting, to see a time before we had invented all the techniques we take for granted in modern animation tools and compositing….

Then of course there’s a soundtrack by none other than legendary trans synth composer Wendy Carlos. Because computers, you see. It’s interesting to think actually - just like the elaborate backlight animation, this is portraying a ‘digital world’ via analogue electronic means.

OK, so that’s how it’s made, what’s Tron actually about? It all revolves around a computer company called ENCOM, basically IBM I guess? It follows the Manichaeist struggle between two programmers: the good hacker Kevin Flynn, and the evil Ed Dillinger who plagiarised his arcade games and booted him from the company. Flynn gets uploaded into the computer world, where he meets his security program Tron, who’s battling Dillinger’s evil AI, the ‘Master Control Program’.

As little as this has to do with how computers work, there are some fun little touches; e.g. the reason the programs take on the likenesses of real humans is justified by the amounts of information already being stored by computer companies. But yeah, mostly it’s a pretty generic good guy vs bad guy sort of script. This was very much a tech demo sort of film, although its imagery has been subsequently enshrined as part of the ~80s~ canon; in fact, it was one of the first films to have a modern nostalgiacore sequel with Tron Legacy in 2010. The lightcycle game devised for the film is quite fun actually - there’s an open source version called Armagetron Advanced which was still in development as recently as Dec 2020. But mostly it’s historically important. And I haven’t seen it, so I’d like to remedy that.

ReBoot (1994)

The next major entry in the ‘what if the programs were like, little people’ genre was ReBoot, the first full CG tv series evar, created by the Canadian Mainframe Entertainment. The idea dates back to 1984 - not long after Tron - originating with a group of British guys called John Grace, Ian Pearson, Gavin Blair and Phil Mitchell. They started experimenting with CG characters pretty soon, in this music video whose animation was done by Pearson and Blair…

…which was one of the first music videos to be ever shown on MTV in 1987, consisting of footage of the band texture mapped into a big rectangle in a CG scene, plus a bunch of digitally matted colour effects. (big shoutouts to @shimakaze-revivalism who was first to show me this!)

For a TV series, though, they needed mooorrrreee poooowweeerrr…… more complex rigs with more polygons and better shading models, which came in the form of Softimage|3D, and work began in 1990, with episodes in 1991. In this world, the computer world is entirely sealed off from any humans outside - in fact, they live in fear of the user, who will slaughter the denizens of the computer any time they play a game. The story mainly follows an action hero called Bob who fights to preserve the city of Mainframe against various villains, all named random computer words like Hexadecimal and Megabyte.

From the outset it faced a censorious Board of Standards & Practices for the US’s ABC network, which seems to have caused a great deal of resentment for the creators; nevertheless the show was a success and gradually started to introduce longer-form stories as the target age group shifted up. The later seasons sound like they went the sort of wild places a long-running cartoon does, with characters aged up by video game time acceleration and an ever-growing cast; as such it earned a pretty devoted fandom who eagerly await the day the creator might decide to resolve the final cliffhanger.

There’s so much of it I could never possibly show more than a sampling, but I would at least like to take a look in to see what the deal is.

Serial Experiments Lain (1998)

There is no possible way I could cover a theme like this without a mention of Lain. The main character of this iconic experimental anime, designed by Yoshitoshi ABe (known as well for Haibane Renmei [Animation Night 106]) has become something of the mascot of a certain species of alienated internet dork. We all love lain.

Lain is… a little complicated to explain, though. The plot summary on Wikipedia throws out a lot of names and concepts which make it hard to get the gist, and the show itself is slow, oblique and requires you to pay attention. But basically it is about an autistic plural girl who becomes God via the internet.

So we have Lain Iwakura. She’s a student at junior high, with little interest in technology, despite her high tech dad. This is the 90s: personal computers are increasingly widespread, but Usenet has only just begun to give way to the Web, and it’s still very novel. Nobody could really imagine what this sort of complex connection would do to the world; it is this context that forms the basis for the original cyberpunk, such as Ghost in the Shell a few years earlier.

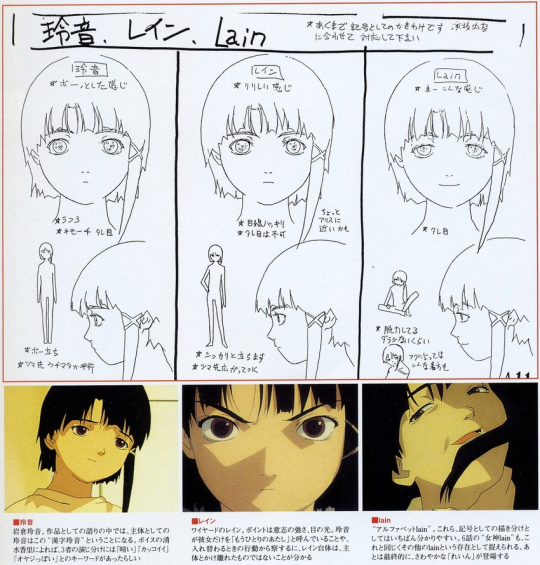

Lain herself comprises three different alters, something never spelled out fully explicitly: the shy ‘real world’ Lain “玲音” (reiin), the ambitious and determined internet delver Lain “レイン” (rein), and the aggressively ‘evil’ Lain (Lain) who harms herself those around her.

Not that what’s around her is necessarily ‘real’ in any truly objective sense; the world of the digitally connected Wired starts to bleed into the real world through some psychic somethingorother involving the Earth’s magnetic field, and the show is always very partial in its viewpoint, preferring to hint rather than really explain anything outright. Lain gradually comes to realise she is not just some random schoolgirl but a kind of omnipotent being that dwells within the Wired all according the complicated plan of an engineer Masami Eiri who uploaded himself into the wired; she finds she can rewrite memories and shape the world as she pleases but this power just isolates her even more.

Along the way we take all sorts of turns, throwing out a plethora of allusions to scientific, occult and UFO conspiracy ideas. Hell, rather than the web, which was in its infancy, the writers looked to a now-obscure hypertext experiment called Project Xanadu. But they’re as likely to throw out a reference to an injoke among LISP programmers. You just have to kind of let it wash over you.

This experimental attitude infects the whole style of the series, making it unique even within anime of the time: its visuals rely on stark compositions of blown-out white highlights and muted greys; its animation is generally very reserved, which does not lessen the impact of striking images like Lain’s room becoming an increasingly alien nest of computers, or the strange partial manifestations of users in the Wired, or indeed the impressive body horror animated by Takahiro Kishida at the finale. Lain’s round face, accentuated by a tiny hairclip, lidded eyes and muted affect captured a certain something that makes her instantly recognisable.

And for that matter the music and sound design is iconic, whether the voice reciting “PRESENT DAY/PRESENT TIME hahahahaha”, the distorted synthesised voice giving the name of the episode, or the fascinating and inspired choice of a song by obscure British Band Bôa for the intro…

Its creators were certainly full of some fascinating ambitions. Notably producer Yasuyuki Ueda declared it a ‘cultural war against American culture and the American sense of values Japan adopted after WWII’ and later said he found himself disappointed that the Americans didn’t come to a different interpretation of the story.

As for director Ryūtarō Nakamura, he worked his way up through the industry since the 70s, notably working under Osamu Dezaki on works like Ashita no Joe 2 and Space Adventure Cobra - perhaps it’s no wonder then that Lain features creative layouts and puts a lot of its narrative in the storyboard. He would go on to direct an episode of GitS:SAC, as well as a well-loved adaptation of the light novel Kino’s Journey, a gentle story which follows a girl on a talking motorbike passing through a series of societies - and working to adapt a Masamune Shirow work with another surreal supernatural story, Ghost Hound, in 2007-8.

And most of the main figures behind Lain - ABe, Ueda and writer Chiaki J. Konaka - would come together again in a cyberpunk dystopian work, Texhnolyze, in 2003, this time at Madhouse. I don’t know a great deal about it, but I’d like to look into it at some point (if not on Animation Night, since it’s a full two cours).

You could easily write dissertations on Lain (I’m sure people have!), but also the chance that anyone in my audience has not seen it is probably pretty much zero lol. But, you know, it’s Lain! I can’t not talk about Lain!

Moving on, here’s another curiosity from the same era which @mogsk sent my way - a 3D animation that attempts to explain how the internet protocol works with physical metaphors, casting various parts of the IP stack as little robot guys. This was animated by Ericsson Medialab, which seems to be… a Swedish telecoms company? It’s cute.

Now, let’s roll the clock forward a few decades. Nowadays, the internet is completely ubiquitous. If you’re anything like me you are almost never not using it for something in every waking moment. But that doesn’t mean technology isn’t making something new and scary; in fact it’s making a lot that’s new and scary, whether environmentally devastating ponzi scheme cancers like cryptocurrency, or the current push by big tech companies to reach the apotheosis of the logic of the social media feed by eliminating human artists from CONTENT CREATION.

So, I thought I’d throw in a look at a largely unacknowledged show that I’ve found kind of interesting from the current year.

Pantheon adapts a collection of Ken Liu stories about a near-future world where uploading has been achieved by a big tech company; it’s similar in some respects to Lain in that it sees students drawn into a world of computer conspiracy. What struck me when I started watching it is how surprisingly well observed the computer stuff is; whether it’s a recognisable 4chan /x/ or a discussion of parallel programming, it’s plugged into the tech world, including its current transhumanist imaginary, in a surprisingly solid way.

The story of the first episode follows a socially isolated and bullied girl at a swanky high tech college who discovers evidence that her deceased dad is actually somehow alive, but only able to communicate in emoji… and a depressed, highly mathematically adept boy whose parents are pushing him very hard to pursue tech who catches wind of the conspiracy. Clearly something big is afoot, and whatever it is, it involves human uploads. I’ve heard a lot of good things, and this seems like the night to introduce it to you guys before I watch more…

Visually, it’s a curiosity: heavily influenced by anime in both visual design and low framerate animation style, and with plenty of solid technical drawing from unusual perspectives, but somehow not quite hitting the notes of timing and motion that give that ‘anime character’. So another note in the general trend of studios around the world turning to anime for inspiration, following in the footsteps of shows like Castlevania.

The main studio credited is Titmouse, although looking at the credits of the first episode, it looks like a great deal of animation was carried out at the Korean studio DR Movie - the same studio that’s currently holding up half the anime industry judging by how often it’s credited. I’d really like to find out more about the exact production process, just for how it fits in to the general debate over how anime’s production process influences the resulting animation.

It clearly owes a lot to Lain, although its approach so far isn’t quite so wildly experimental. And it achieves a strong level of tension already, capturing that uniquely hostile and demanding vibe of the tech world very precisely.

I think that should be plenty. So to summarise, the plan is to watch Tron, and then excerpts from ReBoot, Lain and Pantheon, hopefully enough to get a sense of the vibe and whet your appetite for more. (It’s always tough to know how to handle long pieces of TV animation!)

Animation Night is back to its old timeslot of 7pm UK time, about 30 minutes from this post! I hope you’ll come join me for a dive into visions of the information superhighway, past and present~

Comments