originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/639005...

Today is New Year’s Eve! We’re going to say goodbye to 2020, at last, and I can’t imagine too many people will be sorry to see it go.

Well, it so happens that today is also a Thursday, which means our last Animation Night of the year! And to end this year with a bang, it’s time to do the classic anime film. You know the one - Akira.

There’s simultaneously a great deal to be said about Akira, and not much that hasn’t already been said. But hey, I like writing these things. Let’s add another little bit of Akira adoration to the world.

If you’ve been here from the beginning, you know how much I adore Katsuhiro Otomo’s work in short films in Robot Carnival, Memories, Neo-Tokyo etc., but Akira is his most famous work for good reason. From the absolutely iconic bike chase to the genre-defining cyberpunk megacity of gigantic buildings and sprawling sewers, the fantastic body horror and endless animation flexes of crowds and cloth and water and of course machines… look. look. THEY DID ALL THIS ON CELS, ON CELS, NO CGI, LITERALLY HOW DO YOU DRAW THAT WELL SO CONSISTENTLY… right, breathe!

(How many places have you seen this shot homaged?)

Akira is of course a properly 80s anime - the one that the other 80s anime films like Venus Wars want to be so very badly. It’s got its classic square-headed boy protagonist, its new-agey psychics and evil military men and decaying society. And I mean, you know I love that stuff! But going back to the source like this, there’s a lot of really nice specific touches. It has a unique soundtrack based on a combination of Indonesian gamelan music with noh, which gives it a vibe rarely seen in later cyberpunk. And like much of the original ‘cyberpunk’ canon, there’s a certain sincerity: it doesn’t yet feel like it’s trying to emulate an established genre, but express a view of the world as it seemed to be developing.

So. Let’s situate it! What world did Akira see?

Back in the 80s, Japan was approaching the end of a period of extremely rapid capitalist expansion known back then as the ‘economic miracle’. After the US’s victory in WWII, where they’d infamously used Japan as a test-ground for really terrifying new weapons, the US occupation established various policies and defence treaties in which the Americans would develop the archipelago as a foothold against the Soviet Union, cancelling early moves towards land reform and breaking up the various components of the old imperial system like the the zaibatsu (massive industrial comglomerates), suppressing the yakuza, etc.

So despite massive protests in Japan in the early 60s against treaties ensuring Japan’s close alliance with the US… this kind of policy pretty much set the tone for the rest of the cold war, starting with Japanese businessmen benefiting a lot from providing logistical support to US troops in the Korean war. Throughout this period, the government was seemingly permanently under the control of the same centre-right party for decades on end. The keiretsu, successors to the zaibatsu, grew much bigger, providing promises like lifetime employment: you could spend your entire career working for the same people, and even be buried in a company graveyard. Which meant the people at the top could wield a startling amount of social power.

(If you’ve been here a really long time, you might remember Umineko’s Ushiromiya family built up their fortune through participating in the Korean war logistics effort…)

The rapid expansion of capitalism did not go without further resistance. Most famous is the Sanrizuka struggle, in which large, well-organised groups of helmeted students fought the police using long poles and molotovs in an attempt to prevent the building of a new airport. Memories of these struggles form part of the background to Akira - yet such resistance was unsuccessful, and Japanese capitalism exploded, with all the sorts of social effects you might expect: population getting urbanised (to the point that now only about 10% of the population lives outside of cities??), wealth getting stratified, power blocs like the keiretsu growing…

Presumably, to live in that time, there would have been little confidence that very soon, the economic ‘miracle’ would end resulting in a ‘lost decade’: this rocket was going up, the machines were getting fancier, the money was getting more… but that didn’t mean life was getting better. (c.f. Koyaanisqatsi for another, non-Japanese film of that era with a similar ethos…)

Narrowing in a bit - in the late 80s, when Akira was being made, the economic growth was turning into a land bubble, with Tokyo in particular seeing sharp spikes in land prices which led to, well, lots of land being redeveloped into skyscrapers and gigantic malls, giving a very immediate architectural representation of capital terraforming the landscape. This was also the time when neon signs were really taking off, providing a very striking image full of hyper-saturated colours filling the night with bright semiotic overload.

So the city of Neo-Tokyo in Akira is a kind of extreme, hyperreal version of this skyscraper landscape: the skyline unfolding into layers of larger and larger looming buildings; never mind whether it makes physical sense, the affective experience is suitably overwhelming! Akira goes to enormous effort to sell this city’s sense of place, putting endless effort into detailed, carefully colour-controlled backgrounds, layered compositions and high camera angles to sell the density of this city.

Well, economic data and broad-strokes history is easy to look up; harder to reach from the present is the culture of the time. We can get some idea from the Japanese New Wave film movement, which dealt with much more serious and edgy subject matter, of which someone at the Wiki writes:

Coming to the fore in a time of national social change and unrest, the films made in this wave dealt with taboo subject matter, including sexual violence, radicalism, youth culture and deliquency, Korean discrimination, and the aftermath of World War II. They also adopted more unorthodox and experimental approaches to composition, editing and narrative.

Notable perhaps for us right now is the film God Speed You! Black Emperor (not to be confused with the excellent Canadian band who borrowed its title), which documents bike gangs called Bōsōzuku, the inspiration for Akira’s bike gangs. From the present, I’m not sure how much anxiety over bike gangs like this would have been present in the news…

…but resorting to the text of the film, Akira paints its protagonist gang as good-hearted but helpless, failed by a useless, abusive school system which has little relevant future to offer them, and as the film develops, split by contest over wealth and status. These kids run into a protest and resistance movement trying, no more effectually, to do anything that might interrupt the forces shaping the city.

And into this mess enters the military, which is, naturally, thoroughly untrustworthy and sinister. They’re involved in experiments to develop psychic powers (c.f. cold-war fears inspired by real history of intelligence agencies dabbling in occult bullshit and psychedelics like the CIA’s MKULTRA program, which were far more effective for the looming reputation they created than any actual viable technique for mind control). While much of the city is run-down, the JSDF, signified by blinding spotlights, seems never short on hardware from gigantic helicopters and tanks to, of course, the giant laser satellite.

So, as Tetsuo - the least respected member of the bike gang, ashamed of his inability to live up to the masculine ideal embodied by Kaneda - awakens to psychic powers, the bike gang are swept up into something much much larger, which reflects both the unprecedented kind of destruction wielded by states which now owned nuclear bombs, and the evident ruthlessness of the imperial powers carving up the world. The military want to use the psychic kids to extend their power; Tetsuo, meanwhile, lashes out at their attempts to control him and goes on a rampage/tantrum that’s just a less sophisticated version of the same project of masculine domination.

The other psychic kids, portrayed as frail and wrinkled but with the proportions of children, deliver the most direct, explicit expressions of the film’s themes, albeit framed in rather dubious terms around evolution. But they can’t contain Tetsuo, nor can all the military might of the much expanded JSDF. So it falls to Kaneda, with whom Tetsuo had his only meaningful relationship, to pursue Tetsuo, whose powers are rapidly leaving even his control.

Which means there’s lots of shouting each others’ names lovingly while body horror happens. I actually kind of can’t remember the exact play by play of the ending so it’s gonna be fun for me to rewatch lmao

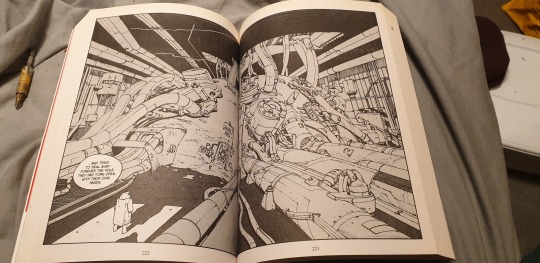

And what of Katsuhiro Otomo, the auteur behind all this? Akira began life as a sprawling manga of thousands of pages, and honestly if the film feels a little like spectacle without substance, it’s worth picking up the manga for a weightier version with a diverging story. Not to mention, Otomo’s drawings are incredibly stylish, every panel loaded with lavish detail.

Otomo got his start in the manga/anime business in the 70s, doing various work illustrating adverts and writing short stories. He started moving seriously into manga and anime in the 70s, starting with shorts like Short Peace; he began the Akira manga in 1982. In some of this work, he was notably assisted by another big name, Satoshi Kon - I talked a little about this on our Kon night.

Otomo was kind of absurdly prolific through this period: at the same time as continuing to publish the Akira manga, he started working in anime in 1987 with Construction Cancellation Order in the Memories anthology, and the titles for Robot Carnival, establishing both his fascination with out-of-control machinery and his dark sense of humour. At the same time, he was busy in production for Akira - though he was not originally planning to adapt it to animation, he was tempted by an offer on the condition of both a bigger budget than any prior anime film and directorial control. Apparently they really trusted him to make a hit, because he got both!

(Incidentally, Akira seems to be an early example of the ‘production committee’ system that would come to dominate anime production, in which many different companies - animators, distributors, etc. - pool funds for a production and share the profits, mitigating risks at the drawback of profiting less if there’s a big hit.)

Of Otomo’s own comments on the manga/film, I’ve been able to track down one particularly interesting translated interview. Some notable answers:

Q. How was Akira born?

Kastuhiro Otomo (KO): I wanted to draw this story set in a Japan similar to how it was after the end of World War II—rebelling governmental factions; a rebuilding world; foreign political influence, an uncertain future; a bored and reckless younger generation racing each other on bikes. Akira is the story of my own teenage years, rewritten to take place in the future. I never thought too deeply about the two main characters as I made them; I just projected how I was like when I was younger. The ideas naturally flowed out from my own memories.

Q. It’s said in France—and in the West in general—that Akira depicts your concerns about political issues, especially nuclear power. Do you think that’s an erroneous interpretation, brought about by cultural differences between Japan and the West?

KO: I’m aware of this line of thinking, but it’s because France takes a philosophical view to everything, distorting it. It’s not how it’s seen in Japan, and it’s not what’s depicted in the comic. I have no intention of expressing my political views or philosophical opinions. I’ve said this often before, but one of my influences as I made Akira was Tetsujin 28-go. This was a manga series meant for kids, with numbers applied to the cast of characters, and I wanted to make an homage to this series. I also wanted to depict the later Showa period (postwar Japan), including preparations for the Olympics, rapid economic growth, and the student unrest of the 1960s. I wanted to recreate the assorted elements that built this era and craft an exciting story that would seem believable enough in reality.

Looking at the world now, I wonder how it wound up like this. Looking at issues like wars/conflicts and organized crime, I can feel the world slowly fall out of balance, and I hope we can improve on that. Basically, though, Akira was heavily influenced by the manga I read as a child, and it portrays this kind of brilliant force that you see in people around the world in their younger, purer years. That’s the simple theme preached by Akira; it’s a tragedy depicting people destroying the world’s balance amid this era that I wanted to recreate.

(it’s funny to me that he dismisses the French, overly ‘philosophical’ attitude and then immediately situates the story a bunch of political and philosophical contexts…)

On matters of craft we also get some great anecdotes:

Q. Japanese critics have praised you for being the first manga artist to draw realistic Japanese faces, as well as for bringing such variety to them and never drawing the same one twice.

KO: I’ve always taken heed of the two key points of fantasy and realism. If one is left too much in the shadow of the other, that weakens the story. Depicting things too realistically actually damages the social realism of the piece, and if you go too far into the realm of fantasy, that hurts its imaginative ability. I’m always thinking about how to balance the two. I think the realism from my early works stems from how I used close friends of mine as character models. My style is naturally built from observation.

Q. In one interview, one of your editors said “In the scene in Akira with the Neo Tokyo explosion, he used a massive amount of crosshatching to depict the volume of the sphere and the way the light hit it. I suggested that painting it straight black, then drawing in white lines would be quicker and easier, but he got angry at me and said he couldn’t do that; not with the millions of people dying inside the sphere.” I think that really shows the relationship you have with your art.

KO: I spent an entire evening gradually blackening that sphere with really thin lines. The editor was pretty alarmed when he saw it, what with all the time it took. But—while you can’t see it since it’s a full-view depiction of the blast—there are millions of lives being lost in this panel. If I wanted readers to sense realism in the scene and feel just how significant this event was, that work spent covering it up in detailed black lines was indispensable.

Making art requires a huge amount of energy and concentration. Drawing accurately, faithfully reproducing characters’ looks, and not relying too much on allure (drawing people too cutesy, etc.) takes tons of energy, to the point where my body can’t take it sometimes. Creativity is all about projecting everything about yourself into your work. You need to have the honesty to fully expose yourself, the ability to recognize your limits, and the power to express how you’re perceiving the world.

I’m always casting these spells to help me find the best form possible for the lines I draw, adding wrinkles to elderly characters’ faces and drawing detail into buildings to help readers dive into the story. When I’m drawing clouds or buildings, I’m chanting at the lines, telling them to “become a cloud” or “become a building.” A lot of other artists have said this, so it may be trite by now, but drawing something is really about projecting yourself into the object you’re drawing. To achieve that, you have to work those incantations into your art—to the point where you might gross out your readers! This is also why I don’t use computers. I don’t need them, and compared to hand-drawn art, that powerful “magic” isn’t as effective. I’ve drawn with computers before, but I don’t like it very much. Doing that means there’s no original in existence, and I like it more when I have an original.

When you’re able to truly draw freely, taking the image in your mind and putting it down perfectly on paper—whether it’s a structure or a pose—you start seeing things you couldn’t see before. You become conscious of that.

And honestly, this meticulous, almost mystical attitude attitude really shows in the film as much as the manga. Find people talk about Akira and you will find someone going on about the enormous effort spent on details that are hidden in backgrounds, or for shots only a few seconds long. You could dismiss this instead a sign of an inefficient production process, but it’s one of those cases where the knowledge of all that work somehow gives the project a special allure even if you don’t consciously notice the bottom layer of background in a six second shot.

[For another interview with Otomo, this one’s pretty good too.]

One of Akira’s best known stylistic touches is the trails of light left in the opening chase scene. This emulates a visual artefact seen on VHS cameras of the time, but naturally stylising and exaggerating - and getting such bright light on cels is a really striking effect, augmented by tricks like underlighting to really push the bright glow. (I remember watching some video on the technique used in the light trails the first time I saw Akira, but I cannot find this information for the life of me…)

But this is just one compositing trick, and Akira has so much more to show when it comes to animating light. From spotlights meticulously wrapped onto a background painting to tiny pebbles casting shadows, just about every shot pays enormous attention to how light falls: loads of rim lighting, saturated colours in desaturated scenes, chiaroscuro compositions, removing backgrounds to emulate the look of the manga (sure it saves costs but like, given how lavish the backgrounds are in other shots…)

Though Otomo is the name most often associated with Akira, certain notable key animators also got their start on this film - for a few examples, Makiko Futaki, known for her later work at Studio Ghibli, did some of the animation of the pulsating, oozing mass that Tetsuo becomes; Takashi Nakamura, who directed the delightful chicken man and red neck sequence of Robot Carnival, created e.g. some of Tetsuo’s vivid dream sequence; Yoshiji Kigami, who later played a tremendous role developing KyoAni, worked on an early sequence with a boy attempting a suicide attack using a grenade.

But the film is carried as much by an enormous team of douga artists and background painters across dozens of studios (including Gainax); videos of the Akira production process usually focus on the background painters carefully drawing each lit-up window…

…but it’s also interesting to read e.g. this interview with a douga artist who moved to America, who discusses how drawing for Akira was, while prestigious, paid at the same piece rates as other anime… meaning it was actually quite poorly remunerated, since the drawings were way more technically demanding than most anime!

So, you know, it’s true what they say: they did everything the hard way, with a bare minimum of digital assistance for digital displays/some help with parallax and lens flares. For more of that kind of thing - while I don’t agree with all of his analysis (a lot of the time I think the lack of backgrounds in certain shots is a sensible choice to focus in), this long video by an American TV animator highlights many of the accomplished technical details of animation, difficult shots etc. in the bike chase.

As much as loving Akira is kind of a cliché for animation fans and scifi nerds - it really is that good! Abstract, mystical ending and all! If you haven’t seen it, I can’t wait to give you the chance.

What happened in the 30+ years after Akira? Sadly, Otomo never got another huge hit like that. He made another lavish feature film in Steamboy in 2004, and wrote the script for Metropolis in 2001, but it seemed anime had thematically moved on and they didn’t have the impact of Akira. (I can’t comment personally since I still haven’t seen them - they’re coming up in a future Animation Night!) His two forays into live action, World Apartment Horror (1991) and an adaptation of Mushishi, were… well the first one was a flop that’s only remembered because it was Otomo on it, the second one seems rather overshadowed by the anime and generally not too well-received. On the other hand, his animated short films have been very good - two brilliant, experimental contributions to Memories (the Cannon Fodder segment, one of my favourite of his works) and Short Peace (the woodblock-stylised segment Combustible).

He also has a son, who’s a talented illustrator in his own right! Shohei Otomo definitely shares some of the cyberpunk tastes of his dad, but takes the illustration style in a more realism-oriented, rendered greyscale direction. It’s pretty sweet stuff, give it a look.

There’s surely more to say about Akira and its relevance today, but we can save that to discuss tonight. I think it’s fitting to end the year coming back to Otomo, and well, a film about a collapsing society and civil unrest and humans losing control of destructive forces seems pretty relevant still! Even if we sadly don’t have cool bikes or psychic powers to lean on.

And, somewhat in advance - a happy new year to you. It’s been a fucked up year but I think we’ve created something pretty damn sweet in this little movie night, and I’m really grateful for everyone who’s dropped by and joined me in enjoying my fave medium. See you at 7pm UK time at twitch.tv/canmom - we should be wrapped up in plenty of time to go and watch the fireworks.

Comments