originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/661876...

So it’s Animation Night 70! Seven tens! We’ve had some good ones recently huh. Going to be hard to beat that.

Back at the start of Animation Night, I set myself a fairly simple rule: none of the really well known Miyazaki/Disney films; if I was going to show anything by them it would have to be at least a little old and obscure. In that spirit, while we did a night on Takahata in which we watched Horus: Prince of the Sun, and watched Miyazaki’s film The Castle of Cagliostro on Lupin III night.

Well, I have arbitrarily decided it’s finally time to give Hayao his due. He is, I can’t deny, something of a very formative influence…

Miyazaki’s career is one of the best documented of any Japanese filmmaker, so strap in, this one’s gonna get long.

If we’re gonna do this, let’s start in the old days! Long before Studio Ghibli became an international household name, Hayao Miyazaki was, as we discussed on Takahata’s night, working at Toei Animation (the first major anime studio) in the 60s on films like Takahata’s Horus. There, he was a close student of Yasuo Otsuka, one of the biggest names in 60s animation, working all sorts of jobs from key animator to character designer. He was also very active in labour organising at the studio from pretty much the moment he joined, a stark contrast to his and Takahata’s behaviour as bosses at Ghibli and A-Pro later in their lives.

I have been able to find out a little more about the labour struggles at Toei, and their significance for the rest of the industry; in this article, in Matteo Watzky writes on the reason they began in 1961, shortly after Osamu Tezuka - already a famous mangaka - joined the company:

Tezuka was very dissatisfied with the modifications to his original storyboard, which is why he only wrote the two other movies. But the production of Saiyûki was capital : Tezuka could see how an animated movie was produced and made a lot of contacts, but also discovered the already very difficult working conditions of animators. Indeed, the director of Saiyûki, Taiji Yabushita, was hospitalized at the end of production, and was probably the first victim of what Yasuji Mori called the “anime syndrom” [Quoted in Clements, 2013, p.103].

These difficult working conditions caused many tensions that exploded in September 1961, with the first strike at Toei. At the time, most staff received a monthly salary, but at the start of the 60’s, Toei’s management started to recruit part-timers that were paid hourly, and did not receive any bonuses. This inequality created tensions among the animators, but also in the rest of the staff, as all the more technical workers (shooting and editing staff, colorists, etc.) were paid significantly less than animators. The studio’s union started pushing for a raise in salaries and bonuses, but the studio’s management refused to give as high a raise as expected. In early December, animators held three two hours strikes, which led to a lockdown of the studio from the 5th to the 9th of December [Clements, 2013, p.104 ; Pruvost-Delaspre, 2014, p.466]. Negotiations ensued and some demands were met, but the ringleaders of the strike were asked to leave. The most prominent among them were two young animators, Gisaburô Sugii and Shigeyuki Hayashi, who would later go by the name Rintarô.

Paradoxically, this strike accelerated the deterioration of working conditions at Toei : the studio started relying more and more on cheaper (and less revendicative) independent part-time staff. In 1965, they stopped paying those hourly, but by the number of cuts, which is now the industry standard practice [Pruvost-Delaspre, 2014, p.460]. In 1970, the studio went even further and fired 43 animators, which provoked another massive strike and another series of voluntary departures.

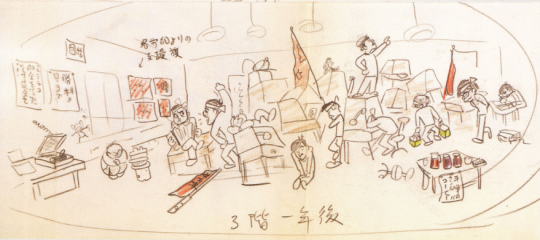

This image from the same article illustrates a strike at Toei in 1963. Yasuo Otsuka is the one standing on the tables; Hayao Miyazaki may be the one with glasses on the far right of the picture.

The labour struggles at Toei were the cause for a lot of animators leaving the studio; Tezuka of course left to found MushiPro and created the TV anime in Astro Boy, creating the tradition of limited animation. Miyazaki and Takahata, however, belong to another lineage - that of realism. They remained at Toei up through 1969, along with Otsuka who stayed to mentor them. On Horus, assigned to the very young untested Takahata by Otsuka, Miyazaki built a number of connections that would stay for the rest of his life, many of them through the union:

The staff was incredibly young : in 1965, Otsuka himself was 34, Takahata 30, Reiko Okuyama and Yoichi Kotabe 29, Akemi Ota 27 (1) and Hayao Miyazaki only 24. The elder of the group was Yasuji Mori, who had been brought into the team after a first stop of the production by Toei’s management to bring some order into this staff of rebellious young people (2). After all, most of them had met in the studio’s union (under Miyazaki’s chairman term in 1964 [Miyazaki, 2009, p.323]) where they both discussed politics and watched animated films from around the world.

After Horus’s very limited release, Otsuka almost immediately defected to the young A-Pro (founded in 1965 by Daikichiro Kusube, in the second wave of departures from Toei). Miyazaki didn’t follow immediately; he spent a few years still at Toei publishing pseudonymous manga People of the Desert, which can be seen as a sort of prototype for Nausicaa, while working on various Toei productions like the tank scenes in Flying Phantom Ship.

During this time, he may well have animated a scene of planes and tanks in A-Pro’s Moomin (1969); a scene that so upset Tove Janson that she pulled the rights to the series and gave them to Mushi-Pro to make instead.

In 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata finally followed Otsuka out to A-Pro, in fraught circumstances: Toei was pivoting to TV animation and dimissing staff left and right, and the union was unable to stop it…

Back in Toei, post-Hols tensions only exploded in 1971, after the death of the creator and head of the studio, Hiroshi Okawa. Following this event, the management confirmed its new priorities : no more ambitions to become the “Disney of the East” that would produce mass-appeal, high-quality feature films, but focus on lower-quality but highly-competitive TV work. That meant leaving aside the remnants of the film-focused production process and relying on a cheaper, more efficient workforce. Concretely, the result was the dismissal of 43 animators. Those left, led by Takahata, organized a mass strike at the end of 1971 and the start of 1972. But the strikers just didn’t have enough leverage, and rather than attempting to change the studio, they left it.

At this time, the system seems to be that TMS Entertainment was the producer on all kinds of series, with the animation work subcontracted out to various Toei offshoots like A-Pro, along with Mushi-Pro offshoot Madhouse. Despite the Moomin catastrophe, A-Pro had big ambitions: an adaptation of Pippi Longstockings. But this didn’t quite happen…

In 1971, as the situation in Toei degraded, Otsuka took up the opportunity and called his comrades from Hols to A Pro where he and Kusube had projected to try another adaptation of a Scandinavian children’s classic, Pippi Longstockings by Astrid Lindgren. Otsuka apparently had little creative importance in the project, led instead by the Takahata-Miyazaki-Kotabe trio : Takahata would adapt the books into a scenario that Miyazaki would illustrate with his recognizable and always rich image boards, while Kotabe designed the characters.

However, that ambitious project would also end up being a disappointment. Tokyo Movie’s director, Yutaka Fujioka, left for Sweden to acquire the rights of the original work, and was accompanied by the trio whose insistence on realism made scouting essential. But the team couldn’t meet Lindgren, who in the end refused to give the rights to Tokyo Movie ; the trio apparently believed that it was because of the Moomin case, which Lindgren had heard about. This is a believable explanation, and the only one I could find, but without any tangible proof…

Although this project was never finished, the work they did became foundational on one of their most influential early projects: Heidi: Girl of the Alps. For this to happen, Miyazaki and Takahata departed to Zuiyō Eizō in 1973, after directing two slice-of-life Panda! Go, Panda! shorts which adopted the slice-of-life sensibility they’d intended for Pippi.

In the next couple years at A-Pro, Otsuka, Miyazaki and Takahata would find themselves working on the very first adaptation of Lupin III, one of the most influential franchises in anime history, during one of the highest points in TMS’s creative output. There’s lots of interesting details in that article which are tangential to telling the story of Miyazaki, so go read it if you wanna learn about the ‘TMS golden age’.

Lupin III: Part 1 (known as “green jacket” to fans of the franchise) has a bit of an odd story, and Watzky devotes a full article to it. A passion project of Otsuka and director Masaaki Osumi, and at first supervised by the mangaka Monkey Punch himself, it was taken in a gritty, seinen direction from its initial pilot - but this did not play well with the higherups:

The first 9 episodes, directed by Osumi, are still close to the atmosphere of the pilot, and of the manga. The animation, while good, feels very rough and the characters are dark, manipulative and violent. Star of the Giants and Ashita no Joe had shown the potential of more dramatic animation that could eventually appeal to older audiences, but this was too much for the time. The series had poor ratings and, as early as episode 2, producers asked Osumi to make changes – which he flat-out refused to do. Under pressure from the TV station, Osumi was progressively relieved of his duties as director while Otsuka introduced his two friends to the series to give them work after the failure of their Pippi Longstocking project.

With Osumi’s departure, Miyazaki and Takahata were brought on board, and their work at this point was a prototype for many of their later movies (including their eventual film adaptation of Lupin III), creating the sort of fun, comic style that became the default tone of the series.

While keeping the fundamental conceit of the series, they started changing the characters and atmosphere of the show. For example, Goemon stops being a dark and dangerous samurai but is used more often for comic relief : Miyazaki himself reminisces about the last episode, where the scenario is pushed to its limits when “we had Goemon tunnel below a huge, seemingly impregnable bank vault and then slice a hole in the floor with his sword, and we showed Inspector Zenigata reduced to tears” [Miyazaki, 2009, p.280]. The general impression given by Miyazaki is that of a chaotic production (he says the producers made apologies to the staff once the show was over), which didn’t stop the staff from having a lot of fun with the thing.

Their work wasn’t quite enough to save the show from poor ratings - it would only get attention in a rerun years later with the second Lupin adaptation.

This brings us to Heidi: Girl of the Alps, probably one of the most important shows for Miyazaki and Takahata and the anime industry as a whole. By this point, the duo were starting to develop strong opinions about what kind of anime they wanted to make, charmed by seeing how children reacted to Panda Go-Panda, and meanwhile they were very disdainful of the limited animation tradition that began at Mushi-Pro and continued at Madhouse. Recognising that they needed to move beyond A-Pro, Otsuka put some effort to negotiate a deal with Shigeto Takahashi where he’d persuade Takahata to go over to Zuiyō Eizō as long as Takahashi would give Takahata a good salary and treatment.

“I’m really grateful to him,” Takahata said in 2004 as he remembered Otsuka’s gentle encouragement to meet with Takahashi. “You can tell he’s looking out for your interests. I’m deeply indebted to him for his help.”

They hit it off really well: both shared a very similar vision for what Heidi should be. Pre-production set off to a good start. Miyazaki remained at A-Pro a little longer, directing one episode of Otsuka’s project Samurai Giants, perhaps as a last favour before he went to Zuiyō Eizō.

As a work of animation, Heidi is remembered perhaps for being uncompromising: TV animation that tried its level best to be film.

What set Heidi apart was its distinct philosophy: one that would be focused on “realism”, an ability to create a believable world, to reproduce the actions and motions of mundane life, and to challenge live-action cinema in terms of technique and staging.

To this end, Takahata brought on many of his colleagues from Horus. Watzky’s article goes into exhaustive detail about some of the major character animators who flourished on the production.

Heidi is often noted for innovations it made to the anime production process, notably the ‘layout system’. After the storyboards (絵コンテ e-konte) were finished, Hayao Miyazaki would draw layouts (aka 1st key animation) as a step prior to the actual key animation. Nowadays, layouts are normally handled by key animators themselves, but this first step has become universal. According to Watzky’s article, there were already a number of precursors to this, but Heidi certainly accelerated its adoption, and provided a particularly developed form, with the layouts often being extensively inbetweened; they were also much more integrated with the background art.

Heidi’s production was characterised by a great deal of centralisation. It had a single animation director checking the key animation for the entire series; it also introduced the role of in-between checking, and further cemented the key animation (genga)/cleanup & inbetweening (douga) divide. It was also notable for making a location scouting trip to Switzerland, an expense almost never indulged by TV animation at the time.

Unfortunately, Heidi also marks a catastrophic reversal of Miyazaki and Takahata’s days as union men advocating for the workers. While early episodes were made with ample time, the production slid behind schedule and increasingly became a crunch time hell.

Things wouldn’t stay so comfortable for long, however; due to the demands put upon the staff by the main trio and especially by Takahata, Heidi’s production quickly spiraled into hell for its staff. According to Yōko Gomi, although Heidi broke many artistic barriers, it also “opened a new and frightening door to a way of working that is not normal for human beings.”

(…)

She mentions that, by the middle of the show (probably around episode 22), the staff started regularly pulling all-nighters – something apparently unusual in anime production until then, outside of exceptional cases like Mushi Pro’s A Thousand and One Nights. By the latter stages of the show, episodes had to be entirely completed in just less than 2 weeks each. At some points, all free or not-so-free hands were put to work: production assistants had to help with cel painting so that the episodes could be delivered on time.

This brutal pace of production led to many animators departing the production. It was also characterised by some really bizarre workplace abuse: badly drawn inbetweens would be displayed on the wall for everyone to see.

Watzky writes darkly, of Heidi’s enduring influence:

It was obvious that Shigeto Takahashi had kept his promise to give Takahata as much rope as possible: now Takahata’s iron-fisted directorial style, with the full support of producer Junzô Nakajima, was unleashed with a vengeance as the entire staff underwent enormous suffering to meet his demands while keeping deadlines. The most remarkable thing is that, under such conditions, Heidi didn’t collapse. It certainly went through drops in animation quality and consistency, as we will see, but it still stood head and shoulders above the standard of most of 1974’s animation. This was perhaps a natural result of the “no failure allowed” mentality: the tension and pressure on the staff were so high that they had no choice but to deliver, and ended up doing so superbly. The fact that they were able to do so would only encourage producers and directors to push them further and raise their standards even more. Such a vicious cycle would go on to become the core not only of Studio Ghibli’s organization, but also of the entire anime industry’s exploitative practices. Of course, Heidi should not be held solely responsible for anime’s problems; but it should never be forgotten that this pioneering and revolutionary show was made in extremely difficult conditions, by a staff which never had to face such things before, under producers who were all too willing (or contractually obligated) to give Takahata the near-complete freedom and authority he needed to pull it off.

Naturally Heidi was an enormous success, providing a powerful launch to Zuiyō Eizō (at some point renamed to Nippon Animation)’s World Masterpiece Theatre programming block.

Following Heidi, Miyazaki’s output seems to have gone quiet for a few years; his next big splash came with Future Boy Conan in 1978, on which he was finally the director rather than the ‘guy who can actually draw’ working under Takahata’s wing.

Conan shows a lot of Miyazaki’s interests as a director: a post-apocalyptic series after an environmental catastrophe, in a world full of boats and planes, with a techno-militaristic threat; all themes that he would develop much more complexly later, but already evident. It was based on a novel, The Incredible Tide by Alexander Key, but soon eclipsed that original. Miyazaki insisted on being able to change the tone of the story, expressing a curious attitude given his later works:

In a 1983 interview with Yōkō Tomizawa from Animage, Miyazaki stated that he only worked on the show under the condition that he was allowed to change the story. He disliked the pessimistic world view of the original story, feeling it was a reflection of Alexander Key’s own fears and insecurities. He wanted a story aimed at children to be more optimistic, stating “[e]ven if someone’s lost all hope for the future, I think it is incredibly stupid to go around stressing this to children. Emphasize it to adults if you have to, but there’s no need to do so to children. It would be better to simply not say anything at all.”[5]

He also attempted to change the story’s geopolitical themes; in Key’s novel, Industria was much more directly symbolic of the Soviet Union, and the protagonist’s home High Harbour representative of America, but Miyazaki (who I believe was still a Marxist at this time) seems to have tried to abstract it.

Animation wise, it took the comedic A-Pro style and turned it more towards the developing tradition of realism. For the sake of it, he pulled in a number of his old A-Pro colleagues, notably Otsuka. By this point, Miyazaki was starting to catch attention. Another catch was Yoshifumi Kondo, who would become one of Ghibli’s core staff, working as animation director on many of their films.

The production of Conan also ran behind schedule, but this time, Nippon Animation had the benefit of working for major TV broadcaster NHK, who had the freedom to change the schedule and insert something else to give them a bit of extra time.

Anyway, there is another note… if you love Eizouken, you may well recognise Conan as the series that inspires the young Asakusa to pursue animation. It remains a very imaginative and beautiful show: not quite as aesthetically distinctive as Miyazaki’s later works, but full of lush sunsets and beautiful environments. I had a still of it as my Tumblr banner for ages… maybe I still do?

A year after Conan, Miyazaki jumped studios again, heading to Telecom and bringing Otsuka with him (with the promise of working on his passion, Lupin III). The Castle of Cagliostro (1979) makes many departures from the usual characterisation of Lupin, painting him as more of a ‘heart of gold’ heroic character; it found success as an astonishing work of animation. We’ve already watched this film (even though I neglected to give it a proper writeup at the time), and I talked a bit about the more questionable side of its lasting influence last week, so I won’t spend too many words on it right now; but it did a lot to establish Miyazaki’s reputation as a film director, an environment he’d find much more comfortable than TV animation.

While at Telecom, Miyazaki started talking to Toshio Suzuki (future Ghibli president) and Osamu Kameyama at Animage magazine, showing them his sketchbooks and discussing his hopes to create two anime projects, an adaptation of Rowlf and a sengoku period story called Sengoku Demon Castle. These were rejected since Animage would not fund something based on manga, but they liked Miyazaki enough to serialise a manga from him, Nausicaa, on the condition that (ironically) it would never be made into a movie. Miyazaki would end up drawing Nausicaa for a good twelve years of his life, and it traces a lot of his slide into despair and evolution of thought towards Mononoke-Hime.

Within a year, Nausicaa had become a hit, and Animage (rather, their parent company Tokuma Shoten) changed their minds and offered to fund a 15-minute film adaptation. Miyazaki proposed a 60-minute OVA; they said hey ok why don’t you make an entire film?

Nausicaa brought Miyazaki together with some of the greatest animators of the era, like Yoshinori Kanada, and even a young Hideaki Anno who drew the distinctive sequences of the God Warrior blowing up the ohms before rotting away. It is a much simpler story than the manga, and yet an absolutely astonishing film on a production level: its animation is both expressive and gorgeously solid, its imagery is exquisite, and they brought on experimental composer Joe Hisaishi who, while he hasn’t quite reached the sound he’d achieve on later Ghibli films, delivers some really beautiful moments.

Since Tokuma Shoten did not have an anime studio, Miyazaki ended up scouting around for one which could handle the project. He landed on a tiny studio called Topcraft, who were at the time mostly known for working on Rankin/Bass productions; but even at this point Miyazaki’s name would draw a lot of talent. But many others were drawn by Kazuo Komatsubara:

The other specificity of the movie is that the animation director wasn’t Miyazaki himself, but someone he had never personally worked with previously: Kazuo Komatsubara. It is most probably Komatsubara who brought on board many “charisma animators” whose philosophy was very different from Miyazaki’s: the rising star of effects animation Takashi Nakamura, the ex-Oh Pro alumnus and studio Z3 member Osamu Nabeshima, and of course Kanada himself. Kanada and Miyazaki had already met a few times by then, and Kanada had even done some of his first in-betweening work on a Miyazaki episode back in the 70’s. But it’s on Nausicaä that began a relationship that would last for a decade.

At Ghibli, Miyazaki would become known as a famously strict director, correcting almost every cut animated for him to ensure consistency in style, such that only truly outstanding animators like Shinya Ohira will be noticeable. This was less true of Nausicaa, which demonstrates many animators’ distinctive approaches; instead Miyazaki exerted his control on the storyboard stage, specifying every moment of the film with unusual precision…

With Komatsubara as animation director, the movie’s animation is probably the most diverse among all of Miyazaki’s catalogue: it’s much easier than in his other movies to spot the different animators and their sensibilities. The level at which Miyazaki exerted his control was therefore not the animation itself, but the storyboards. Especially compared to Rintarô’s, they are very detailed and sequential: every movement and expression is recorded. To put it in raw numbers, Nausicaä’s storyboard is as long as Galaxy Express’ (around 550 pages for each) even though the first one is shorter by 30 minutes and Galaxy Express’s storyboard is already notably long.

Kanada, recently coming off his unsuccessful Birth OVA which we watched some weeks ago, animated the incredible air battle sequence; he would afterwards become a Studio Ghibli regular, but never a permanent employee of the studio, with a slightly odd relationship: Miyazaki’s increasingly strict style would give a famously individualistic animator like Kanada little room to breathe, but Kanada developed his style a lot at Ghibli. But that might be a story for another day.

Nausicaa is a beautiful movie, and on a personal note she’s the only character I’ve cosplayed since I was a kid; it is by far Miyazaki’s most distinctive setting, with the beautiful insectoid “sea of destruction” and the distinctive constructed cultures living around it. It does a decent job of taking key moments from the manga and fitting them into a simpler, closed plot, but it does lack that thematic ambiguity and bleakness which the manga develops in its later chapters.

(I’m well beyond ‘out of time’ here, so I will have to write a proper in depth review of the manga another time. It remains one of my favourite works of fiction ever.)

The success of Nausicaa paved the way for its team to found a new anime studio, Ghibli, named after an Italian aeroplane, which would primarily work on Miyazaki and Takahata’s films. I won’t cover that in detail tonight. But I will talk about Miyazaki’s first film at Studio Ghibli proper (even if Nausicaa was in effect a Ghibli film), Laputa: Castle in the Sky.

Even more so than Nausicaa, Laputa reprises the themes of Future Boy Conan: a boy who meets a mysterious girl in a pastoral post-apocalyptic world full of flying machines, threatened by techological militarism; a cheerful band of sky pirates who inhabit it; a forgotten superweapon. One of the delights of the film is Miyazaki’s interpretation of Welsh miners, who wear the same bushy moustaches as the villagers of Nausicaa and delight in punching the shit out of each other; yet the real star is the Castle itself, a beautiful sandstone creation walked by some delightful robots.

Kanada returned, displaying his famous dragons in the storm sequence; there is a remarkable sequence of a robot burning through a door which I can no longer find. Joe Hisaishi really comes into his own with the soundtrack, too. So let’s watch that tonight, as an illustration of what Miyazaki got up to when he had a studio of his own; perhaps at some point I will get a chance to research its production more.

Since these early days, Miyazaki went through a lot. The following period, with the increasingly bleak tone of the Nausicaa manga and its thematic culmination in Princess Mononoke is one of my favourite periods of his work. His films became much more subtle in tone in later years, with works like Porco Rosso and My Neighbour Totoro delivering a certain wistfulness that is missing from these more clear-cut bombastic earlier entries.

And then you might say Miyazaki became a victim of his own fame, retreating from the struggles that once animated him; sure Spirited Away and Kiki’s Delivery Service certainly still have the goods as very moving stories about growing up, but films like Howl’s Moving Castle turn their lavish animation towards increasingly thematically muddled projects, and eventually we land on unfortunate stories like the honestly painful approach to nationalism in The Wind Rises. (Ponyo’s cute at least… but that’s kind of all it is.) So I can’t help but miss the sheer inventiveness of early Miyazaki: the elaborate worlds, the earnest idealism.

So, the plan tonight is to watch a selection of Miyazaki’s early works: Nausicaa and Castle of the Sky as our main features, but also some episodes of Conan and Heidi! If that sounds fun, I’m going to be starting just about immediately, over at twitch.tv/canmom. hope you can join us!

Comments