originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/137674...

“there is more tea in that sphere than the entire rest of the galaxy” - @rememberwhenyoutried

A Dyson sphere is a thought experiment about an engineering project: by encompassing a star in a sphere of solar collectors, all the energy it emits could be gathered. Dyson (who got the concept from earlier science fiction books, and wrote a paper about the possibility of detecting them) envisioned this as an inevitable creation of an ‘advanced’ civilisation with correspondingly enormous energy needs. For a star like our sun, that means trillions of times more than the current energy use of the Earth.

Dyson spheres show up in science fiction occasionally, usually as a solid shell of matter. (The post that inspired this one was a gifset of a solid Dyson sphere from Star Trek.)

That Wikipedia article is pretty substantial, and covers most of the things I might want to say about Dyson spheres. So all I want to do here is fill in some of the calculations the wiki article leaves out.

Statites (non-orbital satellites)

One of the proposed forms of a Dyson sphere is a swarm of ‘statites’ - enormous solar sail collectors held in place against gravity by radiation pressure. Wikipedia offers a value of the area density that would be necessary for a stable statite.

I have two questions about this: how was this value calculated, and is a statite stable against small peturbations to its orbit?

Calculating the value is pretty straightforward actually - I did it in physics in like second year?

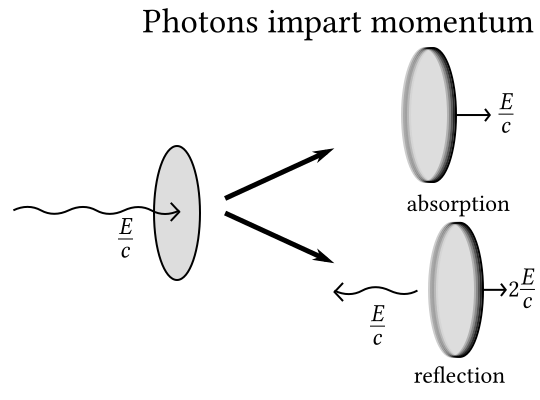

So: solar radiation pressure. Photons carry momentum, depending on their frequency. To be precise, a photon carries momentum $$p=\hbar k=\frac{2\pi \hbar f}{c} =\frac{E}{c}$$ (where \(f\) is the frequency, \(k\) is the wavenumber, \(E\) is the energy of the photon).

Note that the momentum of the photon depends only on its energy. So we can just take the total energy flux on a surface, divide it by the speed of light, and get the force (rate of momentum change over time) per unit area. Sweet!

If a photon hits an object and is absorbed, to balance momentum, the object must gain an equivalent amount of momentum. If it’s reflected back in the opposite direction, the object has to gain twice the momentum of the photon. Which means the optimal situation for a solar sail is a perfect reflector that sends the incident photons exactly where they came from.

OK, so, now, how much force would the solar sail on our statite receive? Suppose the sun radiates a total power \(L\). At a distance \(r\) from the centre of the sun, this is spread over a sphere of area \(4\pi r^2\). So the power per unit area received at this distance from the sun is just $$P=\frac{L}{4\pi r^2}$$ and the force per unit area imparted on the surface, assuming perfect reflection, is $$F_\text{light}=\frac{2P}{c}=\frac{L}{2\pi c r^2}$$

Now, the solar sail is also attracted by gravity, which also follows an inverse square law! The force per unit area from gravity is merely $$F_\text{grav}=\frac{GM\sigma}{r^2}$$where \(\sigma\) is the surface mass density (i.e. mass per unit area).

If our statite is indeed static, the mass per unit area must equal the force of light per unit area, or else it would accelerate. So we can set \(F_\text{light}=F_\text{grav}\) which means $$\frac{L}{2\pi c r^2}=\frac{GM\sigma}{r^2}$$and after a little rearrangement we get that mass density we were looking for, $$\sigma = \frac{L}{2\pi c GM}$$

Plug in the solar luminosity and mass, and you get the mass per unit area of your statite as \(1.53\mathrm{gm^{-2}}\) which is really very extremely light!

A check: this is twice the Wikipedia quote, which cites this Dyson sphere FAQ which makes the same calculation we did, but reports the force of light as half what we had. Although they’re claiming this represents a perfectly reflecting sail, it looks more like they’re giving the result for a perfectly absorbing sail?

I checked my formulae against the numbers in the solar sail article and I believe the calculation above is correct, or at the very least, mistaken in the same way as whoever wrote the solar sail article.

Note also the solar sail would have to be lighter, per unit area, than that value, to account for rigging, electronics, etc. And this is already absurdly light: Wikipedia’s speculation is going as far as suggesting ‘single sheet of graphene’ as a solution.

Is it stable? Actually this is easily answered: the force balance above does not depend on the distance to the sun, so if it moved from its position slightly, it would not start drifting away. However, if the solar sail rippled or rotated slightly from directly facing the sun, it would fall towards the sun slowly; if the solar sail was slightly too big, it would start to blow away from the sun. The statite would have to monitor its position and adjust the sails constantly - but there’s no reason it couldn’t do that.

Solid dyson sphere

So the first thing to repeat is that as a result of the shell theorem, a solid spherical dyson sphere would not interact gravitationally with the sun, and could therefore drift until it hit the sun.

How strong would it have to be? This is discussed in the Dyson sphere FAQ above: they suggest considering the dyson sphere as two hemispheres joined at a seam. Each hemisphere, attracted by the sun, would press against the other: the dyson sphere must be strong enough to resist the pressure from both sides.

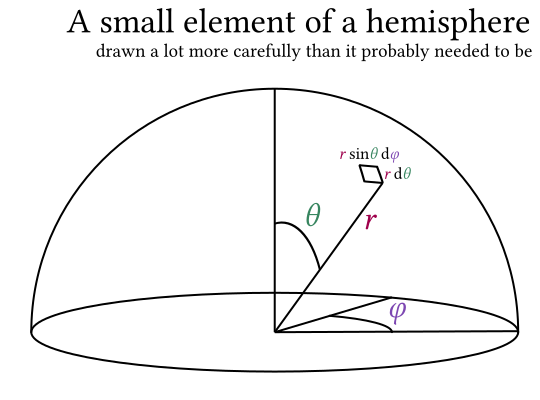

How strongly is a small piece of the sphere, of mass \(\rho t \dif A\), attracted towards the other hemisphere? Here I’m saying \(\rho\) is the density of the Dyson sphere material, \(t\) is the thickness of the sphere, \(\dif A=r^2 \sin \theta \dif \phi \dif \theta\) is an element of area with the spherical polar coordinates shown in this picture:

The force towards the sun is \begin{align}\dif g &= GM \rho t \dif A r^{-2} \\ &= GM \rho t \sin \theta \dif \phi \dif theta\end{align}which is, interestingly, independent of the size of the sphere! The net force in the direction of the other hemisphere is \begin{align}\dif F &= \cos \theta \dif g \\ &= GM \rho t \sin \theta \cos \theta \dif \phi \dif \theta \\ &= \frac{GM \rho t}{2} \sin 2\theta \dif \phi \dif \theta\end{align}

We now need to integrate this over the entire hemisphere to get the force at the join from one hemisphere: \begin{align}F&=\frac{GM \rho t}{2} \int\limits_{\theta=0}^{\pi/2} \int\limits_{\phi=0}^{2\pi} \sin 2\theta \dif \phi \dif \theta \\ &= GM \pi \rho t \left[-\frac{1}{2}\cos 2 \theta\right]_0^{\pi/2} \\ &= \frac{GM \pi \rho t}{2}\end{align}so in fact all we did was insert a factor of pi, huh. Since both hemispheres are pressing with this force, the total compressive force at the join is \(2F=GM \pi \rho t\).

The area of the ‘seam’ between the two hemispheres is, assuming the sphere is thin compared to its size, just \(2 \pi r t\). So the pressure on the seam is $$P=\frac{GM\rho}{2r}$$ regardless of the thickness of the sphere (as long as it’s not so thick that the thickness is comparable to its radius!) We can compare this with the compressive strength of the material.

If the sphere is made of steel, for example, and the sphere is \(1 \mathrm{AU}\) in size (which seems to be the standard example, though it sounds unnecessariy large to me - but also note that the larger the sphere, the less strong the material must be), we find the pressure is \(3.5\mathrm{TPa}\) which is helpfully declared to be nine times the pressure at the centre of the Earth, and seven times the highest pressure sustained in a laboratory. It is, therefore, quite a lot more than the compressive strength of steel, which varies depending on how the steel is made and what materials are used, but might be in the range of hundreds of megapascals and therefore tens of thousands of times smaller what would be needed to hold up a Dyson sphere.

There are two options for making the strength requirement of your solid Dyson sphere more reasonable: make the sphere bigger, and make it less dense.

If you used one of the lightest materials known to humanity, carbon nanofoam, the compressive strength requirement goes down to \(0.28 \mathrm{TPa}\) which is still absurdly outside the realm of possibility.

On the other hand, if you doubled the size of the sphere, you’d halve the strength requirement, but quadruple the amount of material you need.

Worse, if something causes your sphere to buckle towards the sun, gravity will tend to stretch out the distortion, potentially tearing a big hole. Big problem!

This is one of the major reasons a solid dyson sphere is considered one of the least possible kinds of dyson sphere, out of a range of things that are already pretty absurd.

How hot is a Dyson sphere?

Ultimately, whatever solar energy you gather from your Dyson sphere will eventually become unusable heat that you have to radiate away into space to avoid heating up. This is what Dyson was looking for in his paper: a Dyson sphere would radiate a different spectrum of radiation to a bare star, so you could potentially recognise one with a telescope. (People have tried, and not found any evidence of one.)

The radiative temperature of a Dyson sphere in equilibrium depends on its size. The usual rule for emission of something a bit like a black body is that the power emitted is $$L=4 \pi r^2\sigma \epsilon T^4$$where this time \(\sigma\) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, not the mass density, \(\epsilon\) is the emissivity, a number between \(0\) and \(1\) (with \(1\) being a black body) that tells you how well the material emits light, \(T\) is the temperature, and \(r\) is the radius of the spherical body.

The energy coming in to the Dyson sphere (from the star inside) is constant. So you have $$T\propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{r}}$$i.e. the temperature decreases as the inverse square root of the size of the sphere. If we put all the other constants in we get $$T=\sqrt[4]{\frac{L}{4\pi r^2 \sigma \epsilon}}$$and for a \(1 \mathrm{AU}\) Dyson sphere that is a perfect emitter, we find the temperature is about \(120^\circ \mathrm{C}\).

I want to make some metaphor about how like, if you poured water on the surface of the Dyson sphere, it would boil, but you’re in space so that would happen anyway. So instead um, if you had like, a cabin with 1 atmosphere pressure inside, and you had some water in there, it would boil.

If you want to reduce the temperature, make your Dyson sphere bigger, or make some holes in it to allow some of the heat of the sun to escape directly.

I think those are all the questions I had about Dyson spheres answered. For other questions, such as how much material it would take, have a look at the links above, they might cover you! (You are essentially talking about dismantling the entire solar system.) Or ask me. I like talking about stuff.

Comments

matt

There is an error in integrating: (-1/2cos2a) from 0 to pi/2 equals 1, not 1/2.

So the force from one hemisphere F = GMπρt. I guess it’s already the total force, and you shouldn’t double it up.