Last time, we reached a milestone in the project—in theory. However, instead of light falling off nicely from a red light, we’re getting… bright red.

- Fixing the red

- A mysterious resolution difference

- DPI diagnostics

- Intersect some rays

- Using our new collision code

- What next for this humble raytracer?

Fixing the red

So clearly we need to slap a bunch of debugging statements all over the place in order to track down where the problem lies. I currently have two theories…

- the frame buffer contains a list of references to the same pixel object, because the

from_pixelfunction doesn’t do what I thought. That seems unlikely because that would be kind of a ridiculous thing for that function to do. - I’m making a miscalculation in the shading and everything is getting clamped to maximum before sRGB conversion. This is probably it.

So, let’s put some debug statements. First of all, the raw fragments. We’ve derived the ‘Debug’ trait on Vec2 and Vec3, so let’s see if they’re all coming out the same after the shading calculation by printing them to the console.

That would spam our console with \(1280\times720=921600\) debug messages, so let’s… do it every thousandth fragment? Which is to say, every time

(x * 1280 + y) % 1000 == 0

we want to print a debug message giving the value of the fragment.

if (x * 1280 + y) % 1000 == 0 {

println!("Fragment: {:?}", fragment);

}

Here I’m using the println! macro, and string formatting with {:?} which prints the debug message, as described here.

So, after running this, the second hypothesis was right: they’re all much bigger than the clamp maximum. The highest I saw was about 17. So why’s this?

It turns out… I did something stupid lol. I think I edited my shading function in the blog post but neglected to do it in the actual program! So instead of calculating \(\frac{1}{r^2+1}\) like I’d intended, I’m calculating \(\frac{1}{r^2}\) still. Haha…

So I fixed that and… it’s still red. That’s odd… ah, but I think it is actually slightly darker at the edges. The problem is probably that, in ‘world space’, the region we’re covering is tiny. So most of the reds are very close to fully bright red. Let’s introduce a new constant, to determine the rate of falloff - essentially the scale of the world relative to the lights’ height above the ground.

const FALLOFF_RATE:f64 = 16.0;

That fixes it and we get some lovely falloff.

A mysterious resolution difference

What’s confusing me now is that the 720p resolution I set when creating the window does not seem to be applied: the window starts maximised on a 1080p monitor, with the light sitting ( onlyroughly, it turns out) in the middle of that nearly-1080p screen. The image I’m rendering should be 720p in size…

When I resize the window, it crops that nearly-1080p window. The image inside, however, is still blown up larger than necessary.

It’s possible that there is some interpolation going on behind the scenes - some kind of texture filtering on the image. This results in the image being stretched out, and since the image is never redrawn(?)…

Let’s turn off lazy updating? …no, that doesn’t help, nothing changes when I resize the window.

We’re using Glutin as a backend, and that does have a function to make the window maximised or not. The question is, how can I get access to the Glutin window through my Piston window?

A Glutin window, per the documentation, has both a ‘logical’ size and a ‘physical’ size. What seems to be happening is that the ‘physical’ size is much bigger than my ‘logical’ size. nevermind, that’s for dealing with high-DPI displays such as on phones, which mine isn’t. (Actually, past me… you were on to something! —future Bryn)

Looking at the fields of the PistonWindow struct, we see it takes a generic type parameter W is by default a GlutinWindow. Which I assume is a window, since it’s not documented at the top level. Therefore, I’m going to try getting that window field and calling the set_maximized (note to self: the spelling is American) method from glutin to try and make it not be maximised.

window.window.set_maximized(false);

This doesn’t work, but it does tell me what I’m looking at: the type is glutin_window::GlutinWindow. It turns out there’s a layer of indirection: before directly getting into Glutin, we’re first hitting glutin_window, which implements the various traits that PistonWindow needs. This crate’s GlutinWindow struct has a GlWindow field, also called window; now we’re in Glutin proper, and the GlWindow represents a window and an OpenGL context bound together. We can get a reference to its Window object with its window() function.

So in theory, what we want is in fact

window.window.window.window().set_maximized();

This is kind of hilarious. But does it work?

Amazingly, yes… kind of. Our window appears maximised for a fraction of a second and immediately unmaximises. As before, the light is off-centre.

Maybe I need to call set_maximised() before I call build…

let mut window: PistonWindow =

WindowSettings::new("Raytracer", [WIDTH, HEIGHT])

.exit_on_esc(true);

window.window.window.window().set_maximized(false);

window.build()

.unwrap_or_else(|_e| { panic!("Could not create window!")});

That doesn’t work: the build() method is what turns a WindowSettings into a PistonWindow, and it’s the PistonWindow that has the massive nest of windows that I needed to use there.

So I guess the next step is to try and better diagnose the problem. What happens if I put the size of the window to \(1\times1\)? If it’s rendering at 720p and then blowing it up and interpolating, that should lead to an entirely red screen…

…ok, that’s curious. Piston produces a 1x1 window, that’s not maximised. So maybe it is to do with the whole ‘logical’ vs. ‘physical’ pixels thing - and the window I’m drawing is too large for the screen? Maybe it’s trying to draw, say, a \(2560\times1440\) image and maximising the image because it’s too big for my actual screen?

Come to think of it, what if I try drawing the window on my other screen, which is also 1080p but might have a different ‘DPI factor’?

…and on this screen, the window behaves as expected: it appears non-maximised at 720p with the light centred. But if I drag that window from one screen to the other, the image suddenly zooms in by a factor of 2. It really is the DPI factor thing???

DPI diagnostics

I would like my window to render at the same size, regardless of which screen it’s on. So I need to figure out how to shut down Glutin’s ‘clever’ DPI dependent behaviour. When the DPI changes, it triggers an event on the Glutin window.

To make absolutely sure that’s what’s happening, I will add a debug statement to report the size of the window every time it draws…

while let Some(e) = window.next() {

window.draw_2d(&e, |c, g, _| {

println!("{:?}",window.window.window.window().get_inner_size().unwrap().to_physical(

window.window.window.window().get_hidpi_factor()));

piston_window::image(&tex, c.transform, g)

});

}

Unfortunately, this leads to a borrowing clash: apparently we’re borrowing the Window as mutable when we call draw_2d, and trying to borrow it as immutable inside the closure, which conflicts! Damn, this one’s a headache. Maybe we can write the window size on all events instead? For good measure I’ll report all the relevant numbers:

while let Some(e) = window.next() {

let logical_size = window.window.window.window().get_inner_size().unwrap();

let dpi_factor = window.window.window.window().get_hidpi_factor();

println!("Logical size: {:?}", logical_size);

println!("Scale factor: {:?}", dpi_factor);

println!("Physical size: {:?}", logical_size.to_physical(dpi_factor));

window.draw_2d(&e, |c, g, _| {

piston_window::image(&tex, c.transform, g)

});

}

Sure enough, we find out what’s up: the scale factor is 1.0 on my external monitor, and 1.5 on my laptop screen.

There’s no internal way to disable this scaling. I could write a function to handle the scale factor changing and shrink the logical pixels by the inverse proportion, but it’s easier to just set the environment variable WINIT_HIDPI_FACTOR=1.0 on the command line, and lock physical and logical pixels together regardless of whcih screen I’m on. I did that, and everything behaves how I expect at last!

Intersect some rays

Now we have the ability to draw rays, the next question is how to make them intersect with something.

The simplest object we can represent is a circle. A circle is encoded with only two pieces of information: its centre and its radius.

I’ll make a new module occluders to contain representations of various geometric primitives.

use crate::vector::{Vec2};

pub struct Circle {

centre: Vec2<f64>,

radius: f64,

}

The next question is whether I define the collision detection as a method on rays, or on the primitives themselves. I think I’ll just define some generally useful functions on rays, such as the distance from a point, and put the specific collision logic as a trait implemented by things that can occlude a ray, which requires a function that takes a ray and returns whether it collides or not.

pub trait Occludes {

fn hit_by(&self, ray: Ray) -> bool;

}

Then I need to write an implementation of that trait for a circle. That requires us to do some geometry!

If a ray is infinitely long, it hits a circle if the distance of closest approach between the ray and the circle is less than the circle’s radius. The parametric equation of point a distance \(t\) along a ray starting at a point \(\mathbf{o}\) and pointing in the direction \(\hat{\mathbf{d}}\) is…

\[\mathbf{r}(t)=\mathbf{o}+\hat{\mathbf{d}} t\]Suppose the circle has centre \(\mathbf{c}\). Then the vector \(\mathbf{v}\) from an arbitrary point on this line to the centre of the circle is…

\[\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{c}-\mathbf{r}(t)=\mathbf{c}-\mathbf{o}-\hat{\mathbf{d}} t\]The square of the magnitude of this vector is…

\[\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{v}=c^2+o^2 + t^2 - 2\mathbf{c}\cdot\mathbf{o} - 2 \mathbf{c} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{d}} t + 2 \mathbf{o} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{d}} t\]Differentiate this with respect to \(t\) to find the point of closest approach:

\[\begin{gather*}\df{}{t} v^2 = 2t - 2\mathbf{c} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{d}} + 2 \mathbf{o} \cdot \hat{\mathbf{d}}=0\\ t=(\mathbf{c}-\mathbf{o})\cdot\hat{\mathbf{d}}\end{gather*}\]If we substitute this back in to the equation for \(v^2\), find

\[\begin{align*}v^2 &= c^2 + o^2 - 2\mathbf{c}\cdot\mathbf{o} - \big((\mathbf{c}-\mathbf{o})\cdot\hat{\mathbf{d}})\big)^2\\ &=(\mathbf{c}-\mathbf{o})^2 - \big((\mathbf{c}-\mathbf{o})\cdot\hat{\mathbf{d}})\big)^2\end{align*}\]Seeing the result and thinking for a second, we could have found this much quicker with Pythagoras’ theorem, but nevermind, haha.

Assuming both the ray origin and the light are outside any circles, our collision test is

- find the distance from the origin to the centre, which is

origin_to_centre = circle.centre - ray.origin - find the distance along the ray of the point of closest approach, which is

distance_along_ray = dot(origin_to_centre, ray.direction) - if this is negative, return

false- we don’t want to catch objects on the wrong side! - check if this exceeds the distance to the light, i.e. if

distance_along_ray > ray.distance. if true, return false - otherwise, return

origin_to_centre * origin_to_centre - distance_along_ray * distance_along_ray < circle.radius

With a bit of modification, we can account for the ray or light sitting inside circles as well:

- find the distance from the origin to the centre, which is

origin_to_centre = circle.centre - ray.origin - if

|origin_to_centre| < radiusthen return|circle.centre - ray.target.loc| > circle.radius(test if the light is outside the circle) - find the distance along the ray of the point of closest approach, which is

distance_along_ray = dot(origin_to_centre, ray.direction) - if this is negative, return

false- we don’t want to catch objects on the wrong side! - check if this exceeds the distance to the light, i.e. if

distance_along_ray > ray.length. if true, return|circle.centre - ray.target.loc| < circle.radius(test if the light is inside the circle) - otherwise, return

dot(origin_to_centre, origin_to_centre) - distance_along_ray.powi(2) < circle.radius.powi(2)

Let’s translate this to Rust! First, I think I’m going to implement a convenience function to get the squared length of a vector, and avoid taking square roots.

pub trait Squared {

type Output;

fn squared(self) -> Self::Output;

}

impl<T: Dot + Copy> Squared for T {

type Output = <T as Dot>::Output;

fn squared(self) -> Self::Output {

self.dot(self)

}

}

Looking back at all these traits, I am wondering if I would have been better to use references a lot more… but that’s for a future refactor, if it happens. Regardless, now anything that had Dot also has Squared, and I can save myself some clutter.

impl Occludes for Circle {

fn hit_by(&self, ray: Ray) -> bool {

//vector from ray origin to centre of circle

let origin_to_centre = self.centre - ray.origin;

//if the ray starts inside the circle...

if origin_to_centre.squared() < self.radius.powi(2) {

//test if the light is outside the circle

(self.centre - ray.target.loc).squared() > self.radius.powi(2)

} else {

//measure how far along the ray is the point of closest approach

let distance_along_ray = dot(origin_to_centre, ray.dir);

//if the ray is going away from the point of closest approach

if distance_along_ray < 0.0 {

false

//if we'd hit the light before the distance of closest approach

} else if distance_along_ray > ray.length {

//test if the light is outside the circle

(self.centre - ray.target.loc).squared() < self.radius.powi(2)

} else {

//test if the distance of closest approach is less than the circle radius

origin_to_centre.squared() - distance_along_ray.powi(2) < self.radius.powi(2)

}

}

}

}

To make this work, I needed to make all the fields on ray public. I think I’m ok with that, I don’t think there’s any point abstracting this through functions.

How complicated is this? Assuming the compiler is smart about caching stuff it does multiple times, for the case where the ray and light are both outside the circle and the circle is closer than the light…

- two subtractions

- three multiplications, an addition, a comparison

- two multiplications, an addition

- a comparison

- a comparison

- (use cached result?), two multiplications a subtraction and a comparison

So in total that’s seven multiplications, two additions, three subtractions, and four comparisons per ray… I have no idea if that’s efficient!

Using our new collision code

Now we need to make a list of circles to go with our list of lights, and then for each ray test for intersection with every circle before shading. (The next step will be to load these lists from a file instead of hardcoding them into the program!) Firs,t the list of occluders:

let occluders = vec![

Circle {

centre: Vec2 {

x: 0.8,

y: 0.3

},

radius: 0.1,

}

];

The next question is how to iterate over the list of occluders, calling the same function on each one. This seems like a good situation for a map-reduce approach? I will use the iterator function any, and write a closure that calls hit_by on the item it receives.

for light in &lights {

let ray_to = Ray::new(world_space_position, light);

if !occluders.iter().any(|occluder| {

occluder.hit_by(ray_to)

}) {

fragment += ray_to.shade();

}

}

That looks pretty elegant. Hopefully that ‘zero-cost abstraction’ magic will make it fast as well.

Inevitably, we get some kind of complaint about borrowing references in the wrong way. I feel like it would make more sense to borrow a reference to the ray anyway. The question is, how upset is it going to get if I just drop in an &?

…after a minute figuring out where, exactly, the & should be, I landed on this:

pub trait Occludes {

fn hit_by(&self, ray: &Ray) -> bool;

}

fn hit_by(&self, ray: &Ray) -> bool {

//(elided...)

}

I didn’t have to make any modifications to my function. Over in main, I just needed to change ray_to to &ray_to. Now I’m no longer trying to hand over ownership of data where it’s not needed…

After that, it just worked perfectly. The shadow looked exactly right.

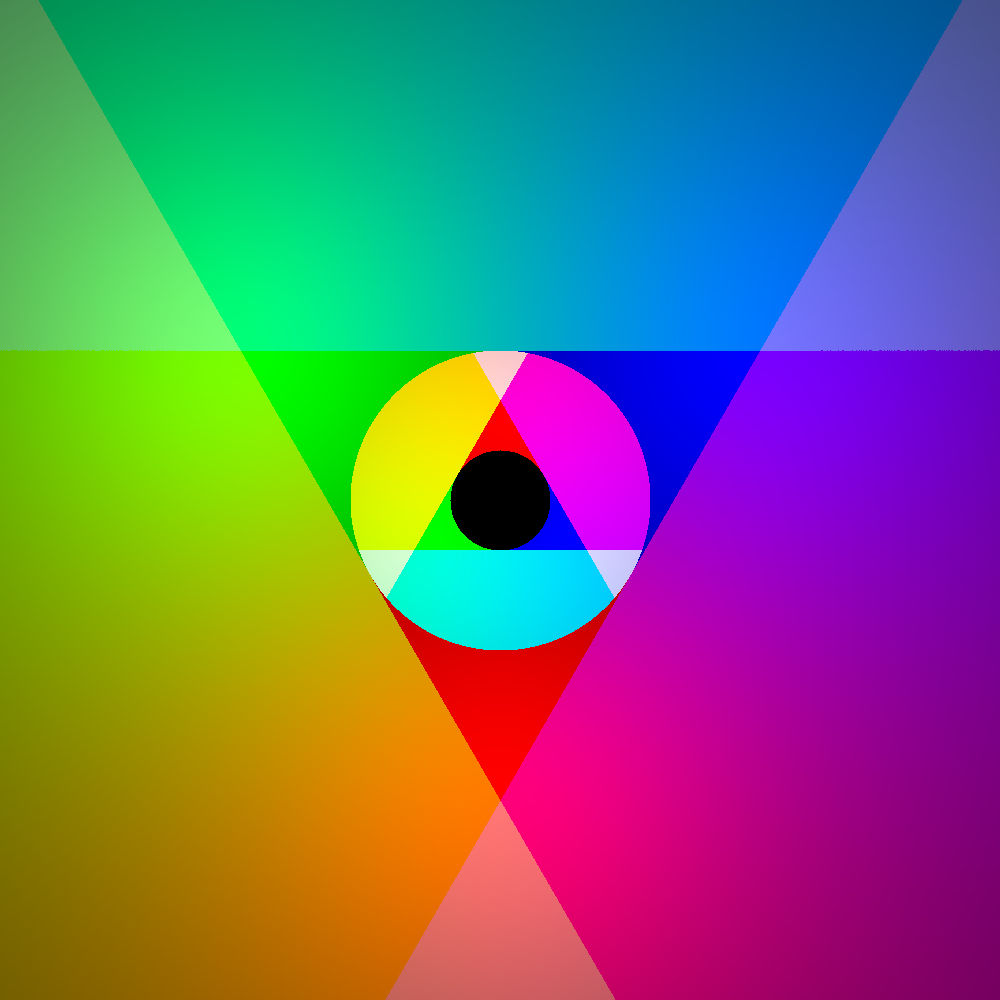

I immediately set about adding more lights to the scene. I’m still compiling in debug mode, so speed isn’t entirely to be expected, but it did take a few seconds to draw once I had six lights and two occluders. The results, though… so worth it!

Look at those subtle colour interactions! Those beautifully smooth gamma-correct gradients with no weird dark bit in the middle! This is wonderful!

What next for this humble raytracer?

We’ve got the basics: we’re tracing rays. If I was at Dawn’s university, this would meet the minimum for the assignment (plus a bit more, since I have coloured lights, gamma correction and son on). But there’s lots more cool stuff to do.

The immediate next step strikes me as handling file I/O. That is, loading lists of lights and objects from a config file, and outputting the image directly instead of making me screenshot it.

The simplest upgrades would be to add more primitives. For example, in increasing order of complexity: straight lines, triangles, rectangles, polygons from a list of points, arbitrary Bézier curves (that last one might be a stretch…)

Apart from, there’s two directions to look into. One is adding user interaction: letting the user drag the lights around (ideally animating in real time, though that might not be possible without invoking the GPU!). The other is something I’ve never tried before: multithreading. Right now our program just runs on a single thread: my CPU has 11 more logical cores (5 more physical cores) that it could be using!

I also want to add more to the rendering algorithm. A simple addition would be ambient light; a slightly more difficult addition would be ambient occlusion based on proximity to a primitive. We could also implement a very basic raytracing algorithm with purely specular reflection, bouncing each ray off primitives according to the standard rule that angle of incidence = angle of reflection for a set number of iterations and then going to the light.

Another cool trick would be to add a texture to the ‘floor’ of the scene - shading the pixels according to their own colour as well as the light colour. We could even give them a normal map (and add the Lambertian \(\cos \theta\) factor while we’re at it)…

But what I really want to try is to move from raytracing to path tracing. That means, we shoot out a ray, and when we hit a surface we find the location the ray hits the surface and cast a new ray in a random direction (but not uniform - we’d use importance sampling to bias the ray we cast according to a direction it’s likely to reflect). We weight each bounce by the Bidrectional Reflectance Distribution Function for that angle. After a set number of iterations, we head directly over to the light as before.

That means we’d need to cast a lot more rays; our collisions would also need to be more sophisticated, since it wouldn’t be enough to just ask ‘does it collide’, we’d need to know ‘where does it collide?’ and ‘what is the surface normal there?’ in order to calculate reflection. Path tracing in 3D produces some incredible images - it would be interesting to see how well it works in 2D…

Comments