originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/750511...

This is a part of a series about TTRPGs! I’m looking at the relationship between the book and the thing you do, the play.

That forum, the ‘Forge’, was founded on the premise that, in Edwards’s pithy slogan, ‘System Does Matter’ - which is to say Edwards believed that the formal and, perhaps especially, informal procedures you follow when you play a roleplaying game have a large effect on what kind of experiences you can have there. Kind of tautological, but I’ll let him have that. It is true that there are many different activities that fall under the heading of ‘tabletop roleplaying’.

Edwards and his pals wanted to have a more explicit and intentional ‘creative agenda’ when playing a game. In general this is something that the players were supposed to get on the same page about when they sit down to play a game. To the Forge mindset, the ideal is for everyone to be pushing harmoniously to the same thing; the root of ‘dysfunction’ in TTRPGs was seen as arising from an unacknowledged clash of these agendas.

The solution found by the Forge was to design new game systems which put their preferred agenda, ‘narrativism’, front and centre.

Many more words could be written about the Forge, a lot of them quite mean, but let’s bring this back to game design. What is it good for?

- why do we buy all these books anyway?

- let’s talk D&D - on the ‘proper’ way of playing the game

- It’s pretty, but is it D&D?

- the scope of the book

why do we buy all these books anyway?

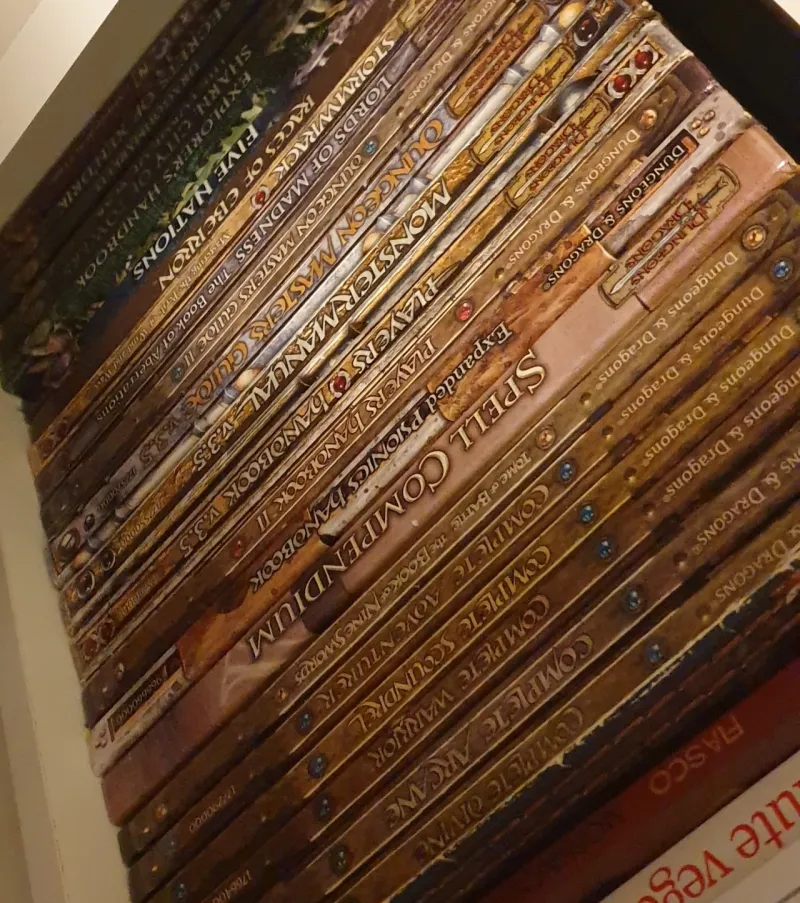

What is ‘an RPG’? On the shelf to my right are… hold on let me count… some 27 different D&D books, mostly from 3.5e. Also a couple other TTRPG books (including Apocalypse World). On my hard drive are… some 94+ other games accumulated from various Humble Bundles and similar. I have played only a small fraction, and honestly, read only a slightly larger fraction.

What is a ‘game’ in this context? Generally speaking there’s a book, and maybe some other tools like character sheets, which theoretically provide what you need to get together with some friends and do an activity that it defines. Sort of like a recipe. But the book itself is not the game; the book anchors the game, which is something rather nebulous, into a thing that can be bought and sold. The game is an activity, which ‘exists’ when it gets played. However, consulting the book is (usually) part of the game!

I rather vaguely say ‘what you need’, because it’s more than just ‘rules’. Lancer, for example, is full of colourful, vivid pictures of giant robots; these pictures do a lot to get players’ imaginations thinking about what sort of giant robot they might pilot - how cool it would look and what sort of sicknasty shit it would do. I doubt Lancer would be even a fraction as popular if it didn’t have these artworks to get you on board with its fantasy. The pictures are a very load-bearing part of creating the ‘game’ here.

We could say the aim of the TTRPG book is to convince you that the game “exists” in a concrete enough way that you can actually play it. Much like the Golden Witch, BEATRICE. Then you can gather your friends and say, ‘hey, do you want to play Sagas of the Icelanders’, and they will say ‘yeah, what’s that?’, and you’ll show them the book and sit down and attempt to follow whatever idea the book has imparted of ‘how to play Sagas of the Icelanders’.

So, the relationship between TTRPG book and play is rather nebulous. This is something of a problem if you are an aspiring auteur designer who would like to impart something specific to players. Who knows what they’re going to do with that book?

let’s talk D&D - on the ‘proper’ way of playing the game

D&D is the oldest roleplaying game, and still by far the biggest. Many TTRPG players will only ever play D&D. Many others will play games derived from some version of D&D, like all the different games belonging to the ‘OSR’. It’s a point of endless frustration for indie game players, who have to deal with being a satellite to this juggernaut, which they see as poorly designed. If only these players would recognise how could they could have it!

But the interesting thing about D&D - and TTRPGs in general, really - to me is that it’s folklore. It’s not a product you buy.

How do you learn to play D&D? You could go and buy the ‘core set’: the famous Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual and Dungeon Master’s Guide, a tripartite division that has existed since the days of AD&D. However, for all their glossy art and flavour text, these books still do a pretty dire job of actually getting you up to speed on how the game is played, especially for the Dungeon Master.

No, what you actually do is: you join an existing D&D group. Or, in the modern day, maybe you listen to an ‘actual play’ podcast such as Critical Role. This furnishes you with a direct example of what D&D players say and how that results in a story, far more vividly and concretely than you’d ever get from looking at a book.

Once you’re convinced that you wanna join this weird little subculture, then perhaps you go and grab some books, run a published module, create a character, whatever. Maybe you go on D&D forums and read endless arguments about the best way to play the game, which all the while serve to define what that game actually is in your head.

A lot of critics of D&D complain that the rules of D&D as written do a pretty terrible job of facilitating many of the purposes that D&D is put towards. They tend to argue that there are games better suited to it, often from the story-games milieu. If people say ‘sure, but we change the games in x, y and z way’, this is seen as a bit of a joke - “well you’re not really playing D&D at that point, are you?”

If you view ’D&D’ as defined by what’s printed in the books printed by Hasbro, sure. However, D&D is not really that. D&D is the label we apply to a huge nebulous body of lore, from the Dread Gazebo and Tucker’s Kobolds to weirdly endearing monsters derived from knockoff tokusatsu figurines. It is all the ideas you’ve received about what it looks like to play D&D from listening to a podcast. It’s arguing about what Chaotic Neutral means. It is 50 years of material - of frequently dubious quality, mind you! - that exploded out from that time some nerds in the States decided to explore a dungeon in their wargame.

If whoever had the rights to use the Dungeons & Dragons trademark never printed another book, that would not kill D&D. In fact, there’s even a condescending nickname, courtesy of Edwards, for people who cook up their own slightly-different spin on D&D and try to sell it - the ‘fantasy heartbreaker’. The concept of D&D has considerable inertia.

It’s pretty, but is it D&D?

In this perspective, defining what D&D ‘is’ with a strict demarcation is kinda impossible. Gygax himself was very inconsistent on this front, favouring strict adherence to rules at times (declaring of houseruled games that ‘such games are not D&D or AD&D games - they are something else’), and encouraging changing them at others - rather depending on whether he had the rights at the time, and his conflict with Dave Arneson.

“Since the game is the sole property of TSR and its designer, what is official and what is not has meaning if one plays the game. Serious players will only accept official material, for they play the game rather than playing at it, as do those who enjoy “house rules” poker, or who push pawns around the chess board. No power on earth can dictate that gamers not add spurious rules and material to either the D&D or AD&D game systems, but likewise no claim to playing either game can then be made. Such games are not D&D or AD&D games- they are something else, classifiable only under the generic “FRPG” catch all”

In this he sounds rather a lot like Ron Edwards declaring that only his perfect design is the true and correct version of Sorcerer! And to both these fellows, we should say, who gives a shit.

So at this point, beyond the (so far) 11 ‘official’ versions of the books published by TSR and later Hasbro, there are hundreds of offshoots that bear a heavy amount of D&D in their lineage and function almost identically even if they don’t bear the trademark… and an uncountable number of small variants, whether explicitly houseruled or just different habits forming from ‘who speaks when’ or ‘what rules we ignore’ to the focus of the game.

So. Imagine a person who was inspired by the D&D milieu, gradually figured out their own taste of what they like to see in a TTRPG over many games of ’D&D’, and is now having a good time playing a game of ’D&D’ about tense feudal politicking, even though they almost never look at a D&D sourcebook and frequently defy the rules printed in there. Is this person ‘playing D&D’?

How about someone playing an OSR game derived from early D&D, that can’t legally use the D&D trademark, but still uses THAC0 and maybe the occasional Mind Flayer®?

Now let’s try someone who read Apocalypse World sometime and got inspired to try DMing in its style - asking players leading questions, acting to separate them, applying a cost to a desired thing or rearranging things behind the scenes when a roll goes bad… but they still consider what they’re doing to be D&D, and they’re strictly speaking playing by the book? After all, D&D doesn’t say a thing about whether you should do that stuff or not.

Bit of a tough question imo! Maybe we should call Wittgenstein.

the scope of the book

There are so many different kinds of TTRPG book.

Some are very specific - a game like Lady Blackbird, The King is Dead or Hot Guys Making Out overlaps heavily with something like an adventure, giving you just one very tightly defined scenario and mechanics that only make sense in that context. This isn’t a new thing, either - a game like Paranoia (1984) is designed with a specific game structure in mind, where the characters each have a variety of explicit and secret objectives that are all at odds with each other.

D&D was originally a game like this, though it didn’t last long. The earliest editions of the rules instruct the referee to draw out ‘at least half a dozen maps of his “underworld”’ filled with monsters and treasure, representing a “huge ruined pile, a vast castle built by generations of mad wizards and insane geniuses”. As far as I understand the history of the hobby, though, people almost immediately started getting into character and using the game for other things than exploring a dungeon.

Other game-products leave larger gaps to be filled in by the player…

- a game like Shadowrun or Eclipse Phase, or D&D settings like Dark Sun or Eberron, will give you huge amounts of information about its setting, but leave ‘what you do it in’ to the GM’s discretion.

- a game like D&D gives you various setting elements, and there are many adventures and modules you can elect to ‘run’, but it is the GM’s task to pick and choose some subset of those pieces and build them into a custom setting for that game.

- a game like Apocalypse World gives you quite explicit instructions for how to set up a first session, and works very hard to set a vibe with the many examples and general style of its rules, but it tells you next to nothing about a predefined setting.

- a game like Fiasco or Microscope offers only a loose structure, that your job is to fill with content over the course of the game.

All of these games market themselves with the same type of promise: with our book, you will be able to have this kind of experience. Like all marketing, they will tend to overpromise! But the marketing is, vexingly, itself part of what makes ‘the game’ happen.

In the video, Vi Huntsman roughly argues that this marketing is the core of what Root: The RPG is actually doing, trying to sell you on Forge ideology rather than provide anything helpful for running a tabletop game; and that the way it attempts to provide this experience is through crude ‘buttons’ which are inherently limiting, belonging more to the mechanistic worlds of computer games or board games than TTRPGs.

I kind of agree, but the problem is that… to some extent every game does this exact kind of marketing. For example, here’s the Bubblegum Crisis RPG (yes, there was a Bubblegum Crisis RPG, published by Mike Pondsmith’s company R Talsorian Games in 1996) which announces:

Those words are lyrics from several songs from the Bubblegum Crisis soundtracks, and they encapsulate the kind of action and drama you’ll find in the Bubblegum Crisis Boleplaying Game. With this book, you’ll enter the world of MegaTokyo and the oppressive megacorporation Genom—a world where monstrous Boomers, desperate AD Police and the mysterious Knight Sabers battle for the future of civilization.

This copy serves as a promise of what the game will bring, but also a prompt that tells you what kind of game you should use its tools to make. It’s attached to exactly the sort of licensed game that Vi Huntsman criticises, applying an existing framework to a licensed RP as if to imply you need this book in order to tell a Bubblegum Crisis-inspired story.

Why? Huntsman called it ‘reproducibility’. If every game that ever runs is a uniquely circumstantial snowflake, there is nothing to sell. But if you can offer someone the tools that they surely need to do that thing they heard about…

The problem is that what makes an RPG memorable is something that arises when you get a group of friends (or strangers!) to sit down together and make up a story, and that kind of definitionally can’t be reduced to instructions in a book - it’s too personal, too specific to the people involved. But we live in the era of capitalism, so… RPG companies and independent designers alike need to have a product to sell to this ‘RPG player’ subculture-identity.

The drive to somehow make reproducible experiences dates back all the way to the very first time people heard about that crazy game that Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson were doing at their wargames club and Gygax and Arneson decided to print a book to help people do that at home.

And with many RPGs on the market, they need further to differentiate themselves: to tell you that they’re offering something you can’t get elsewhere.

So what is that something? In the next post I’ll get into that!

Comments