A friend was asking about this so I thought I’d write a quick post to explain the basics of privacy type stuff…

First of all, don’t take it from me. The EFF is much more involved in like, keeping people safe and private online, and they’ve made a detailed guide; one girl is not going to tell you everything you need to know! But bearing that in mind…

- How the internet works

- Hiding what you’re sending

- Hiding where your messages are going, and come from

- Browser tracking

- Keeping your accounts secure

- Talking to people safely

- Securing a device

- Summary

How the internet works

Whenever you do something online you send one or more packets across the internet. These packets are labelled with the destination IP address (so they can get there) and your own IP (so they can get back).

Every computer that’s connected to the internet has an IP address, and what happens is that your packet is passed from router to router, and at each router it attempts to work out the best way to the destination IP and sends the package on to the next router.

The package contains certain information: “I want to see this page” or “my password is…”, and when the server gets it, it will usually send a response: “this page contains this information…”

Of course, you need to know the IP address of the server you’re trying to talk to. Your computer does this using the Domain Name Service, which are a few servers around the world that will tell you that, for example, ‘github.io’ has the IP address 185.199.109.153 (and a couple of others - you can test this using the nslookup program if you’re on Linux).

So in the most basic model, you can be spied on when you send a packet to the DNS to find out the IP address to connect to, and again when you send a packet to the server…

- when the packet leaves your computer (your internet service provider - it can see what you’re sending, and where it’s going)

- any of the routers your message passes through along the way (same as your ISP - can see where the packet came from, where it’s going, and what you’re sending)

- when the packet arrives at the server (the server itself can see where the packet came from, and of course what you’re sending, but that’s the whole point!)

- any of the routers the server’s reply passes through along the way (an attacker can read where the reply is coming from, where it’s going back to, what the server is sending back)

- when the reply from the server comes back to you (your ISP can read where the reply is coming from, what the server is sending back)

So suppose you want to make it harder for someone to track you. Perfect security is impossible, but let’s see what the options are…

Hiding what you’re sending

If you want to hide what you’re sending from your ISP and anyone along the way, you and the server you’re talking to need to encrypt the message. In general this is done using Transport Layer Security (TLS). For websites, you know you’ve got TLS turned on if you’re using HTTPS instead of HTTP.

If you have a modern browser like Firefox or Chrome, and the server you’re talking to supports HTTPS, it should automatically use HTTPS. Generally, you can trust that HTTPS is turned on and set up correctly if there’s a small padlock icon next to the URL in your browser. And you can also look at the beginning of the URL: if it says https:// you’re using HTTPS, if you’re using plain HTTP it wil say http://.

HTTPS doesn’t stop the server you’re talking to from tracking you - because you have to tell them this information to do anything at all. In this case, Tumblr’s server knows what post I’m typing, what blogs I visit, etc. But nobody in between me and Tumblr should be able to find that out - they only know that I’m talking to Tumblr, not what I’m saying.

Some older servers still use HTTP instead of HTTPS. This is not too much of a problem if you’re not sending sensitive information such as passwords. A static website with just HTML is already putting its contents on the internet for anyone to read, so you’re not gaining much by encrypting that information when it sends it to you!

However, if you’re sending sensitive information like a password, a modern browser should warn you if you’re using HTTP, and it’s worth checking the URL in the top of your browser to make sure it says ‘https’ and not ‘http’. Sometimes a server isn’t designed to automatically switch to HTTPS if you try to connect with HTTP, but you can do it manually - though if it’s a badly designed website, it will put you back on HTTP.

You may sometimes see a warning that a page is supposedly using HTTPS, but there are items in the page such as images which would be loadd using additional requests with HTTP instead of HTTPS, which means someone spying on your connection could see these items. I believe modern versions of Firefox block these items unless you tell it otherwise.

Sometimes sites will not have HTTPS set up correctly, or at all. Getting HTTPS set up requires that you sign your messages, and without going into too much detail, you need to register some information with a trusted authority for that to work. This generally speaking costs money. If a site has an improperly configured HTTPS certificate - perhaps it has expired, because certificates only last for a limited period - you have the option of adding an exception, but you should be very careful doing this, because it could be a sign that someone is trying to impersonate the site and intercept your connection.

For older, no-longer-actively-maintained websites, nobody is going to update them to use HTTPS. For this reason, there is a danger in being too overzealous in promoting HTTPS (as Google are being), because it is a technology that favours people with the capital to get their certificates set up properly, and we could lose a lot of online history if we block access to HTTP-only websites. If an old website is using HTTP instead of HTTPS, that’s fine - just be careful what information you send them.

Hiding where your messages are going, and come from

The other thing you may want to hide is where your messages are going, where they come from, and what protocol they use. To solve this problem, you’ll generally use a VPN (Virtual Private Network).

I’ve previously written a long post about VPNs, so I won’t try to recap that in too much detail. But to summarise…

When you use a VPN, your computer encrypts the packet it would normally send straight onto the internet, and sends that encrypted packet to the VPN’s server first. The VPN decrypts the packet, and sends it on to wherever it was going before.

As far as anyone after that point knows, the package comes from the VPN, and when the final destination server replies, it will reply to the VPN. The VPN will then encrypt the reply and send it back to you.

So the VPN hides what you’re sending and who you’re sending it to from your ISP and anyone who intercepts the packet before the VPN server, and hides where your messages come from the destination and from anyone who intercepts your messages after the VPN server.

If you’re up against someone with loads of resources, such as a government, they could attack the VPN by doing traffic analysis, looking at when encrypted packets arrive at the VPN server and when decrypted packets leave, and using that to attempt to match the two. That’s the problem that TOR is designed to help solve - it’s basically three layers of VPNs that are constantly changing the particular route. But bear in mind that if you’re up against something like that, you shouldn’t be getting your security advice from some girl on tumblr.

There are hundreds of VPNs to choose from; you can see some comparisons at this website.

Browser tracking

You can use a VPN and HTTPS to help protect against people intercepting your packets, but neither of them prevent the servers you’re talking to from tracking you. In the past that would just be the server logging ‘I got a request for xyz file from this IP address’, but nowadays there’s a whole lot more going on.

Modern browsers run a programming language called JavaScript which allows web pages to send you programs which your browser will run. While old websites were just static pages (pages without JavaScript) and links which tell the browser to request another page, a lot of modern websites run on JavaScript for some or all of their functionality. Social media sites and web applications like Tumblr, Facebook, Twitter and Discord completely break without JavaScript.

That’s fine as it goes - but you’re basically giving any website you connect to a carte blanche to run whatever program they want, limited only by the restrictions on the browser! JavaScript is designed with some limitations - a JavaScript program is not supposed to be able to affect files on your computer, or other webpages you have loaded in your browser. But even without breaking those limitations, you can still do a lot with it.

In addition to JavaScript, sites can store a small piece of information called a ‘cookie’ in your browser. This can be used for good purposes - most of the time, when you log in to a website with a password, it sets a cookie in your browser that means you don’t have to put in your password every time you visit a page on that site again. But…

For most social media websites, their business model is to gather as much information about you as possible and sell that information to advertisers to target advertising more effectively. One of the most telling pieces of information they want is to know what websites you’ve visited.

Most websites get their tracking scripts from a third party provider, such as Google Analytics. In the simplest case, a tracking script sets a cookie in your browser the first time you visit a new website, and then every time you visit a website that’s running the script, it will ask the browser for that cookie and use that to record that you were on that website.

Tracking scripts don’t necessarily just record what websites you visit - they can also record where you move your mouse, what you click on, things you type; anything really.

Since people have gotten wise to this and started blocking cookies, modern tracking scripts use much more sophisticated methods to ‘fingerprint’ your browser and identify you when you load a new website. They also have tricks such as invisible ‘pixels’ that can detect what sites you’ve been on even if those sites don’t run the tracking script!

Also, seemingly innocuous bits of website functionality, like a ‘like’ button that you can use to quickly put a Facebook or Twitter ‘like’ on a site… also track you! And they associate that tracking with your Facebook or Twitter account.

It’s fucked up.

So what do you do about it?

Browser extensions to restrict tracking

If you live in the European Union, the new GDPR regulations theoretically mean that sites have to tell you when they’re using tracking scripts, and give you an option to refuse them. I say theoretically because many sites aren’t necessarily in proper compliance with GDPR, and it’s going to take a while for various court cases to shake out. And in any case, they’ve been tracking you right up until the GDPR regulations came in.

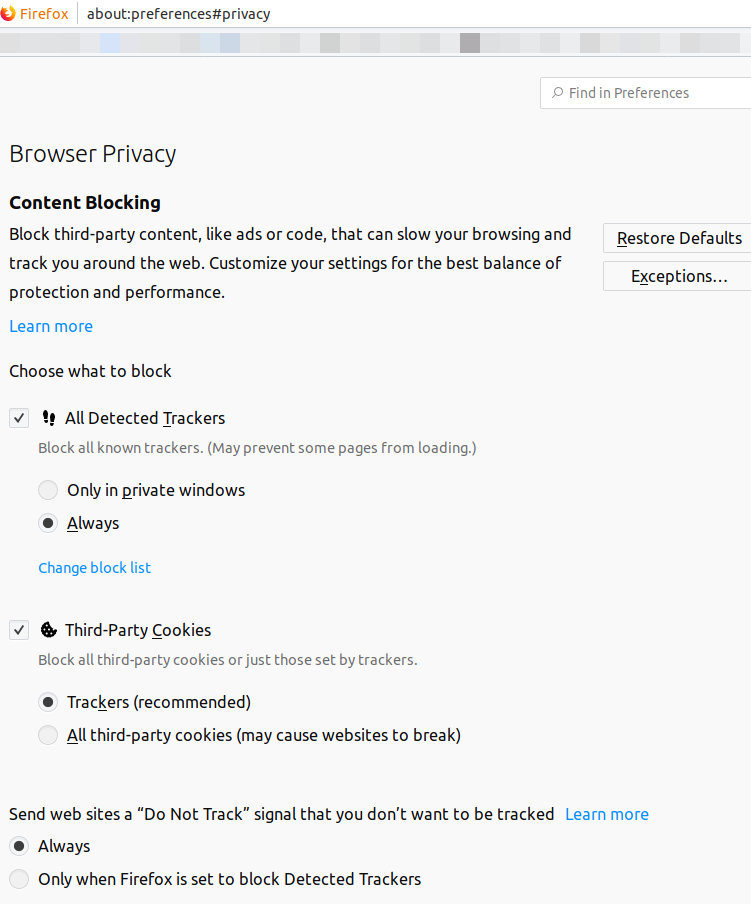

The first step is to, as much as possible, kill the tracking scripts. Firefox recently added an option to the browser to do this: go to about:preferences#privacy. I imagine there are similar options in Chrome. You’ll get something like this:

This depends on Firefox having an up-to-date list of trackers, of course. In addition ‘Do Not Track’ signal sends a message with the requests you send to say ‘pls don’t track me’, but like… it’s entirely up to the trackers whether they want to respect that.

On top of this, you may want to run uBlock Origin, available for most browsers. In its default settings, this will block all ads, which very often contain tracking and analytics scripts, and also various tracking domains. Of course, by refusing to load ads, you are potentially depriving sites of ad income. If there are specific sites you would like to be able to show you ads, there’s a convenient button so you can disable uBlock on those site, or you can make it only block a list of known trackers and still load ads if you really want to lick capitalists’ boots.

These systems tend to work on either a ‘blacklist’ of known trackers. We’ll get to more severe blockers in a moment which block everything until you manually whitelist sites, but somewhere in between these two extremes is Privacy Badger by the Electronic Frontier Foundation. This extension attempts to automatically detect trackers, by watching their behaviour, and blocking them if they do tracker-like things.

Now, what if that’s not enough? If you want to take a ‘whitelist’ rather than ‘blacklist’ approach - block all JavaScript until you specifically say ‘this one can run’, this can be done with an extension called NoScript.

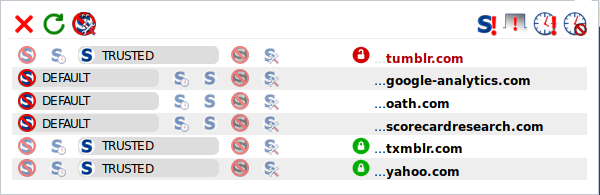

NoScript blocks all scripts until you specifically allow them. By default, when you go to a site with NoScript turned on, if it depends on JavaScript, web fonts etc., it will likely not work. You choose which domains get to run scripts - which is useful because most sites get their tracking from a third-party website. For example, on Tumblr, I’ve allowed some domains that are required for the site to work, and disabled ones that are purely tracking:

You have more fine-grained control - you could say for example that a site can load web fonts, but not run scripts.

If NoScript breaks a site - which it occasionally does, often (annoyingly) with banking sites or payment systems - you can disable all blocking in a particular tab, and that’s usually enough.

NoScript will make the web much more fiddly to use. It will break most sites until you work out which script domains it’s depending on to run - and some sites, particularly newspapers, will have a list of dozens of domains, most of which are trackers, but a few of which might be essential, so getting them working without also allowing the trackers in will be a pain. This illustrates a general principle: more secure is usually less convenient. It’s up to you where you want to put that tradeoff.

And it won’t kill all tracking; if yahoo.com is running a tracking script (which it probably is) in addition to whatever it does that the rest of Tumblr depends on, I can’t block one and not the other.

If you want even more control than NoScript, you can use uMatrix. Where NoScript lets you blanket block or allow a particular domain, uMatrix allows you to let one site run scripts from a particular domain without necessarily allowing other sites to run scripts from that domain. That’s more control than I tend to really need, and a bit too fiddly for me, so personally go with the combination of NoScript and uBlock Origin.

That’s going to catch a lot of trackers, and punch a bunch of holes in the information that companies can gather on you, but it won’t stop the scripts which you can’t kill without breaking websites. So what else can you do?

If you want to be extra paranoid, you can start a new ‘private’ browser window every so often. In theory, this means that your history, tracking cookies etc. only last as long as that particular session, and get deleted afterwards. So the tracking won’t be very useful in that case - they’ll not be able to see your entire history, just that session. However, tracking scripts try to work around this with ‘fingerprinting’ methods which capture information about your browser settings to try and identify you.

Another option, if you want to simply keep activities separate from each other - e.g. if you’re a sex worker and you want to keep your work social media accounts separate from your everyday life ones - is to create one or more new browser profiles, and switch between them. In Firefox, this is described here.

Of course, as soon as you log in with an account on a social media site on a particular profile, whatever you do with that account will be connected to any other actions you take using that account.

Handling social media

Unfortunately it’s very difficult to avoid being on social media. Especially since most of us, when we were younger and social media was new, overshared a bunch. So Facebook remembers an awful lot of information about you. Even if you’ve unliked pages, locked down your privacy settings etc. … that information is out there.

There’s no really strong way to force a social media company to forget about you - you’re pretty much just limited to asking nicely, in the ways they allow, and hope they’ll delete the stuff you tell them to delete. In some countries you may be able to take them to court, but that’s something I wouldn’t know much about, and might expose you to more harm.

In theory (as often required by law), most social media websites have a deletion policy - you can say ‘please delete my account’ and they will wipe the data they have on you, after a certain amount of time. Of course, this kind of ‘scorched Earth’ approach is costly - you’d have to rebuild your connections on a new account.

As a less extreme measure, you will generally want to go into the privacy settings of every social media account you own, and lock them down as much as possible. The specific method will depend on what sites you’re on, but have a poke around in their settings page to see what you can turn off. This won’t stop Facebook knowing about you, but you can get them to promise not to share your info with advertisers, and prevent random people from seeing sensitive information.

One option to try and introduce some separation in the information is to do the step mentioned above of running different browser profiles. You can log into different accounts, and while Facebook (say) will know about each account, it won’t necessarily know they belong to the same person.

Limiting the info you upload to the internet

When you take a photo with a digital camera, it often stores extra information in the file, describing what kind of camera took the picture and sometimes, location data - this is called Exif data. If you then upload this image to a public website, someone can check the Exif data and find out where it was taken, or similar information.

Since people have started being aware of the problem, social media sites have started removing Exif data from images, but you can’t be totally sure unless you do it yourself. While I haven’t tried it, a look around seems to suggest Exiftool is the most effective tool to strip Exif data from images. You can also use an image editor like GIMP or Photoshop to remove the Exif data and re-save the image.

Keeping your accounts secure

Maybe - because we have no choice - we accept the devil’s bargain of letting a social media company profile us in return for the connections it makes possible. But just because you’re prepared to let Facebook profile you, doesn’t mean you want any old random person getting that information. So you need to keep your accounts secure.

In general a lot of that is on the company’s side of the fence. They shouldn’t ever store passwords directly, but hashes - essentially a ‘one way’ function that you can apply to a password that produces some random-looking gibberish that’s specific to that password. When you log in with your password, they’ll take what you send them, hash it, and compare that with the hash they’ve saved - if the two hashes match, then they can assume the passwords were the same and let you log in.

The idea of the hash function is that calculating a hash fast enough to not cause an annoying delay when you log into a site, but slow enough that someone who’s taken the hash and is trying to crack passwords has to spend an impractically long time to hash every single possible password until they find the one that produces the right hash.

Sometimes, companies get hacked, and often when that happens the hacker will get a bunch of account details, including hashed passwords, and put them on the internet somewhere. You can check if you are in such a breach on haveibeenpwned, and as of recently, you can even get Firefox to alert you if you’ve been in a fresh breach.

After these breaches, people will try to crack those hashed passwords, by running the hash function thousands of times per second on various ‘trial’ passwords. These password-cracking systems often start with lists of common passwords and mutate them in various ways, and can exploit graphics cards to run loads of trials in parallel. Nowadays they’re terrifyingly fast.

There’s various standard hashing techniques, and people have already spent a long time hashing possible passwords and making lists of passwords which correspond to particular hashes. As an additional safety measure, before they hash your password, the company should first combine it with a ‘salt’ - a bunch of random data that’s stored alongside the hash. So someone trying to crack your password can’t just look up the known hashes, but has to start from scratch with each salt.

That’s the theory. What you want then is a password that is going to be hard to crack even if someone gets their hands on the salt and the hash. That means you want to maximise the entropy of your password - a measure of the amount of possible passwords that you’d have to test before you hash the right password. That means a longer password, and a password that uses a wider set of characters.

Creating a strong password

So for example, if you used an eight letter password made of random lowercase letters (each letter could be one of 26), the number of possible passwords is \(26^8 = 208,827,064,576\). That’s about how many the attacker would have to try to get a good shot at finding your password. That sounds like a lot, but it’s actually not that many for a modern GPU-based password cracker. We say the entropy of the password, measured in bits, is \(\log_2\) of the number of possible passwords - so the entropy of this password is \(\log_2 208,827,064,576=37.6\) bits. Every random letter you add to the password from an alphabet of \(L\) letters increases the entropy by \(\log_2 A\).

Note that this applies if the attacker is expecting you to use a completely random password. Most people, however, use a dictionary word, or worse, a bunch of common passwords such as ‘password’ and ‘1234’. Generally password crackers will start with testing these kinds of password, and variants such as ‘passw0rd’, which will catch a lot of passwords dumped in a breach. Don’t be one of those people!

There’s two common approaches to strong passwords. The safest place to store a password is in your head, so one way is to just create a strong password and memorise it. Unfortunately, an approach that makes a strong password - a series of completely random letters, numbers and symbols - is also something that makes it really hard to remember a password. So there’s two answers to this problem.

One answer - famously popularised by xkcd - decides it’s easier to remember a sequence of random words. If a the person trying to guess your password doesn’t know that you generated a string of random words, they’ll have fuck all chance of guessing it, because your password will be dozens of letters long, and the entropy will be enormous. If they have worked out that you’re using a string of random words, it’s like a sequence of letters, but the ‘alphabet’ for each letter is the number of words in the dictionary.

One way to generate this kind of word password is diceware. This gets you to roll dice to pick words off a list. The list has 7776 words on it, so for example if you use an eight-word diceware password the number of possible words is \(\log_2 7776^8=103.4\) bits of entropy. Bearing in mind that the difficult of guessing a password goes up exponentially with the entropy, you can trust that someone won’t crack this hashed password.

Another option, slightly riskier, is to use a pseudorandom number generator. This is a computer program that creates random-looking numbers. Because computers are deterministic at heart, this isn’t perfectly random, and it’s possible that there will turn out to be a way to predict the sequence of numbers and compromise a password generated this way. But if you’re prepared to take that risk, xkpasswd gives you various options to generate a passphrase this way, with options to increase entropy by capitalising some words, adding digits etc., and tells you the entropy of the password you generated.

However, most of us are registered for hundreds of different websites, and we don’t have space in our brains to memorise a long passphrase for each one. Reusing the same or a similar password on multiple websites is a bad idea. If the password is cracked in even one place - because one company was lax in using the strongest hashing algorithms, for example - then the attacker will be able to open up the rest of your sites. If you’re lucky, you’ll hear about it first and have a chance to change them all.

This is where password managers come into play. There’s a few out there - I personally use Password Safe on Windows and Android, and Password Gorilla on Linux, which can open the same files. These programs can generate very long pseudorandom passwords for each website and store them in an encrypted file, and you just copy and paste them in.

Then there’s a question of where to store this file. If it’s online (on a cloud storage site like Dropbox), it could be downloaded—you have to trust that the encryption, and the password you’ve chosen for it, are sufficient to stop an attacker opening it.

So as for where to use a passphrase, and where a random password in the database…

- I would say to use a passphrase for your email account, because if you can’t log in to other sites (you’ve forgotten your password, or it glitches out), they will probably give you the option of resetting your password through your email. If you lose access to your password database (say it’s on Dropbox or a similar service), getting in to your email can get you back into Dropbox. But that means that if someone else gets access to your email, they can use that feature to bypass all your passwords. So make it a strong one.

- Your password database itself can’t usefully store its own password, so give it a passphrase. Again, make it strong. If someone gets in there, they have everything.

Everywhere else, I generate 32+ character passwords (unless, as is frustratingly often the case, their policy puts a maximum length on passwords - which is just unnecessarily making passwords easier to crack. Password Safe and Password Gorilla both have random generation options that can be made to fit various schemes though.) Sometimes you might run into weird bugs - a site lets you register with a 15-character password, and then won’t let you enter a password of more than 14 characters for example. But most of these are easy enough to work around.

Two-factor authentication

If you want more security than just a password, a lot of sites now offer two-factor authentication (2FA). This means you set up an app on your phone, and give it a key from the website (usually by scanning a QR code), and your phone can then use the current time to generate a special code that you give the website in addition to your password. This code changes every minute or so. In theory, this method means that nobody can log into the website if they don’t have your phone.

The drawback of this method is that if your phone ever gets broken or lost, you can’t log in either! If you’re lucky, you’ll still be logged in on some other computer, and you can use this computer to turn off the 2FA. You will also be given a bunch of backup codes when you set up 2FA - these codes can be used in place of the 2FA codes generated by your phone, but each one only once. You should encrypt these (e.g. in your password database) and use them to turn off 2FA if your phone breaks.

Another trick is to get a physical USB key which contains encryption information. Some sites can be set up so that you need this key to be able to log in. The same risk applies - lose the key, you can’t log in.

Talking to people safely

Until recently, having secure conversations with people online was very difficult. Although you usually use TLS to send messages to a service like Discord or Facebook Messenger without them being intercepted, the messages are accessible to the company running the server (and can therefore be used for advertising etc.), and can be ordered to be shared with governments.

But the rise of Signal means it’s actually pretty easy to set up secure chat now.

Signal provides end-to-end encryption (meaning someone intercepting messages can see that you sent a Signal message, but not what you said), and you can set messages to disappear after a certain period of time. The main limitation is that it requires all messages to go through the Signal servers, which see which phone numbers are communicating - although Signal promises they don’t store this information, if they were compromised, it could allow a map to be made of who is talking to who. Without using services like a VPN or TOR, it will also be apparent that user is using Signal, even if it can’t be seen who they’re talking to with it.

Another, very young alternative is to use Briar, which relies on a decentralised system and TOR routing to create anonymous forums that are copied onto every device, and can work locally over Bluetooth and Wifi even if the internet is unavailable.

The more old-school method is to use GNU Privacy Guard (an open-source implementation of Pretty Good Privacy, sometimes referred to as PGP) to encrypt your emails. This requires that you obtain and verify the recipient’s public key, and they need to have the software on their end. You can get GPG plugins for certain email clients, such as Thunderbird. This hides what you’re saying, but it will be possible for someone intercepting the email to see what email address you’re sending it to. Because GPG is a bit of a faff to set up, it’s never really caught on among anyone but security nerds, but it’s strong if you can get people to use it.

Securing a device

Of course, securing your messages in transit is useless if someone gets their hands on your phone (say an abuser, a cop/state security agent, or someone who wants to steal your credit card details). What do you do to stop that?

First of all, if someone gets their hands on your device, you don’t want them to be able to get in and use it. This is another tradeoff between security and convenience. Biometric systems like the ones on some modern phones, which allow you to use your fingerprints, irises or face to quickly unlock your phone, are generally not very secure against a dedicated attacker - they can be fooled relatively easily. Swipe patterns are less secure than passwords, but faster to put in. A reasonably long password or code is the best option.

Even if they can’t get your phone to unlock itself, an attacker could take it apart and get the data off the disk itself, or replace the phone’s software with something that will let them read data off the disk. For maximum security, you would completely encrypt the data on your device - this is called whole disk encryption. This will mean that even if an attacker gets your computer or phone, if they don’t know your encryption passphrase, they can’t decrypt the data on it.

Recent versions of Android support this kind of encryption, as do a lot of modern Linux distros. There are some drawbacks; since the system has to encrypt and decrypt every time it reads and writes to disk, your computer will be slower to load and save files. If you don’t want to encrypt your entire disk, or you want to lock down only parts of a system, you can encrypt individual files. The password databases mentioned above are one example of an encrypted file.

Whatever software you run on your device, you are only as secure as the vulnerabilities of the software. Keeping your computer secure is such a sweeping problem that it’s way more than I can discuss here. Probably the most effective option is to get a computer with a lot of memory and run Qubes, which roughly speaking runs every application in a separate virtual machine, meaning that if an application has a vulnerability it can’t compromise other applications without escaping the virtual machine (generally something that’s extremely difficult to do).

In general, turn off ways to communicate with other devices such as Bluetooth and Wifi if you’re not actively using them, since they may have vulnerabilities that you don’t know about.

If you have network equipment like routers (or worse, ‘internet of things’ devices), make sure to change default passwords (how to do this will depend on your device). More recently, router companies have gotten a little bit wiser about not putting the same password on every device, but it’s best to check. This is unlikely to be a targeted attack, but you don’t want your router to be part of a botnet DDoSing random websites.

Of course, none of this will stop someone using the threat of violence to force you to open your devices for them.

Summary

The more of these you do, the harder it will be for someone to gain information on you:

- use a high-entropy, randomly generated, unique passphrase or password on every website and never store passwords in plaintext, only in an encrypted database

- keep an eye out on haveibeenpwned and change your password immediately if one of your accounts shows up

- use two-factor authentication wherever it’s available (drawback: requires a phone, must keep the backup codes safe)

- use HTTPS wherever it’s available to access websites (generally speaking, this is enforced by default in modern browsers)

- turn on your browser’s anti-tracking settings, and use uBlock Origin and either PrivacyBadger, NoScript or uMatrix (drawbacks: the last two will require you to do some fiddling when you visit a new website)

- use a VPN and/or TOR to access the internet (drawbacks: costs money to use a VPN, a VPN is slower than normal internet and TOR is slower still)

- delete old social media accounts, and lock down the privacy settings on the ones you still use

- scrub EXIF data when you upload files, and take care to only upload things you are comfortable being public knowledge

- where possible, only talk to people with Signal, Briar or GPG (drawback: requres that the other person is also using that software, can risk losing access to your messages if there’s a technical hiccup)

- encrypt your devices and use a strong password to secure them (drawback: can’t access that data if you lose the key)

- virtualise everything using Qubes (drawback: requires you to learn how to use Qubes, requires more memory than a normal operating system)

Comments