We just introduced the most important tool of perspective drawing: the vanishing point. Let’s summarise what we’ve learned:

- Parallel, infinitely long lines in world space all connect to a specific point in canvas space, called the vanishing point.

- The ‘distance’ between vanishing points is the angle between the directions they represent. The closer you place vanishing points representing a particular angle, the wider the field of view of your picture.

- The view angles are more and more ‘stretched out’ across canvas space the further you get from the principal point (the point where your gaze is perpendicular to the image plane). This reaches an extreme for directions that are parallel to the image plane, whose vanishing points are infinitely far away.

That’s all well and good for lines, but what happens when we connect these lines up to make planes?

Plane basics

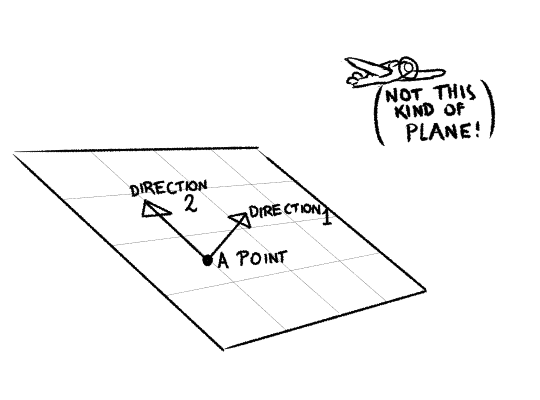

Here’s a quick summary of plane facts. A plane is a flat surface in 3D space. You can define a plane by picking one point in the plane, and two different directions. These two directions run along the surface of the plane, and we can find our way to any point in the plane by moving some amount along one of the directions, then some amount along the other.

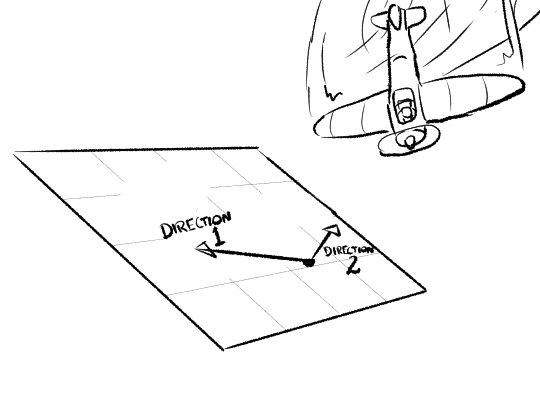

Note that while two lines and a point define a plane, there are many different ways to get the same plane using two lines and a point. For example, the plane we just drew, we could pick out a totally different point and directions:

Note these two directions also give us a third direction, perpendicular to the other two, called the ‘normal’, which points away from the plane. But more on that later!

Planes can be parallel to lines, meaning no matter how far we spread the plane out, and no matter how far we extend the line, the line will never pass through the plane. If a line, which we’ll call Lana the Line, is parallel to a plane, we can find some line within the plane which is parallel to Lana. Planes can also be parallel to other planes

Planes can be infinite, or they can have a boundary. Of course, a plane with a boundary is just part of an infinite plane, so we deal with them in the same way. In perspective drawing, a lot of the time we’re concerned specifically with squares and rectangles, planes whose boundaries are made of four straight, perpendicular lines.

We like planes because they’re a lot easier to understand than other shapes, and because we can approximate a curved surface with a bunch of tiny little plades.

Vanishing lines

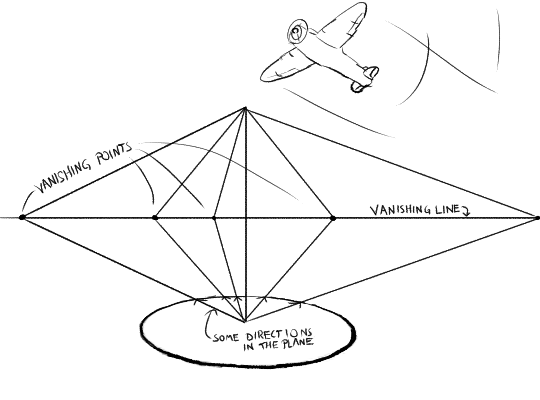

A family of parallel lines in perspective all point to a vanishing point. What about an infinitely big plane?

A plane contains an infinite number of different families of parallel lines, each of which has a vanishing point. If you were to draw all of these vanishing points, it turns out… they all form a line in canvas space!

The horizon line

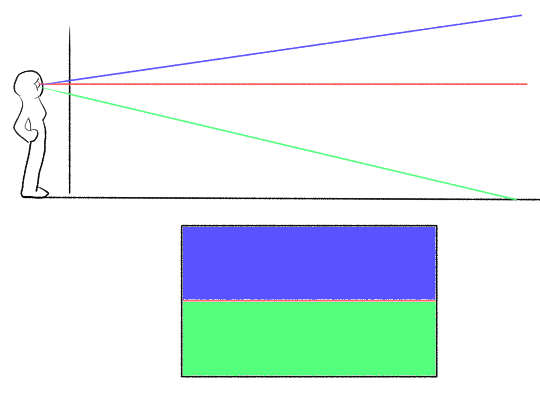

This is most commonly seen when we deal with the ground plane, which is a good place to start. Imagine we’re standing not on a spherical Earth, but an infinitely large flat plane, with the canvas vertical. We shoot lasers out of our eyes as usual.

We can divide the lasers into two classes. If they’re angled below the horizontal, they will eventually hit the ground. If they’re skimming exactly along the ground, or pointing above the horizontal, they will not hit anything but sky. In canvas space, this corresponds to dividing the picture into a side that’s ground and a half that’s sky. The boundary corresponds to the lasers that are exactly parallel to the ground plane.

“Now hold on a minute,” you (might) say. “We live on a spheroid, not an infinite flat plane! Objects such as ships don’t recede infinitely far away, but disappear over the horizon, starting with the bottom. And they start to disappear like this only a few kilometres away.”

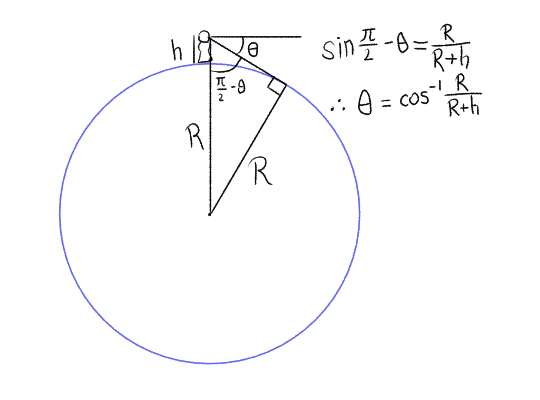

If you said this, you were right. The ‘horizon line’ in a perspective drawing will actually be very slightly above the ‘horizon’ as seen on Earth… except for hills and stuff, which will probably have the opposite effect. But the difference is so small that it is unlikely to be discernible. We can actually work out how far the Earth’s horizon is below the perspective horizon using some circle geometry:

For a 2m tall person standing on a 6371000m radius Earth, this turns out to be… 0.05°. You’re absolutely not going to be able to draw difference that without a gigantic piece of paper/stupidly high res digital canvas and an implausibly sharp pen. And if there’s hills and stuff, they’ll cause much more disruption to the visual horizon.

This is why we can get away with calling the vanishing line of the ground plane the ‘horizon line’: the Earth is really fucking big. If we lived on a tiny little asteroid like the Little Prince, we’d have to be more careful in our terminology :p

Vanishing lines in general—let’s build a ramp!

So, there’s a horizon line. What about other planes, not parallel with the ground plane? Where should the next vanishing line go?

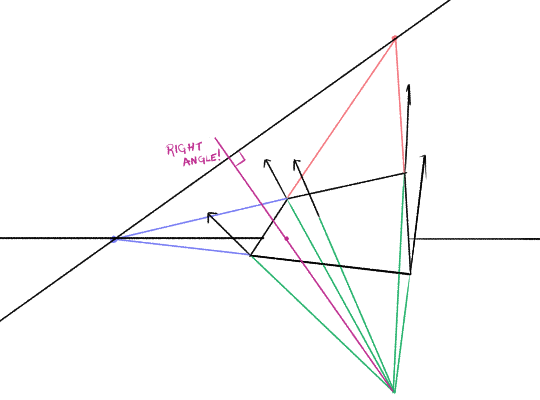

Well, to start with, you can always rely on vanishing points. If you already know two sets of parallel lines in this plane (easy if it’s a rectangle), you can draw their vanishing points, and then draw a line connecting those vanishing points, and that’s the horizon for this specific plane.

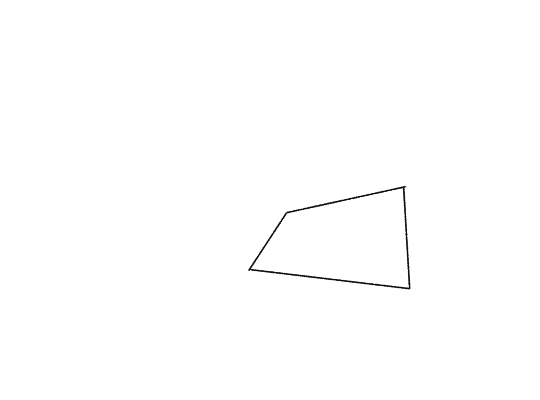

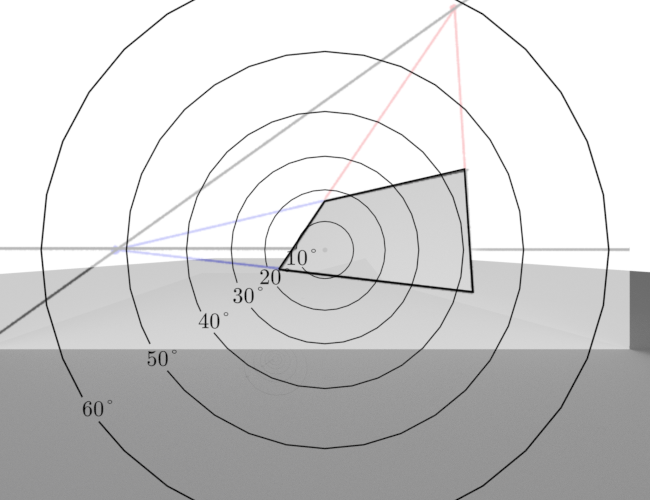

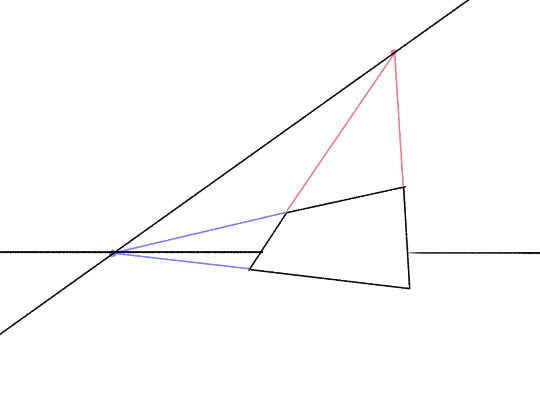

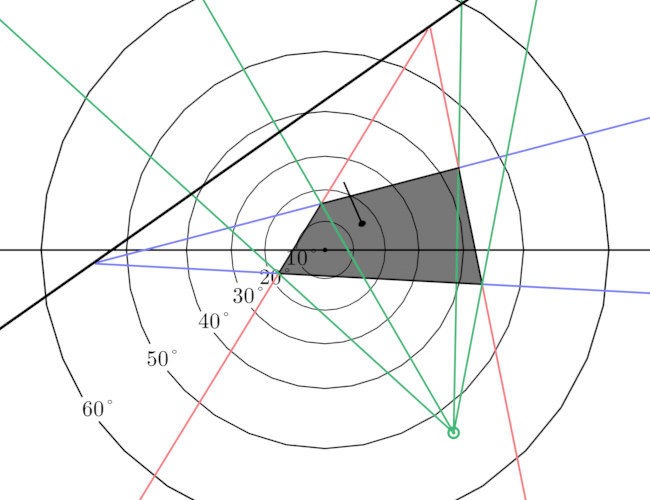

For example: here’s a quadrilateral. This could represent a rectangle in perspective, but it’s not flat to the ground plane.

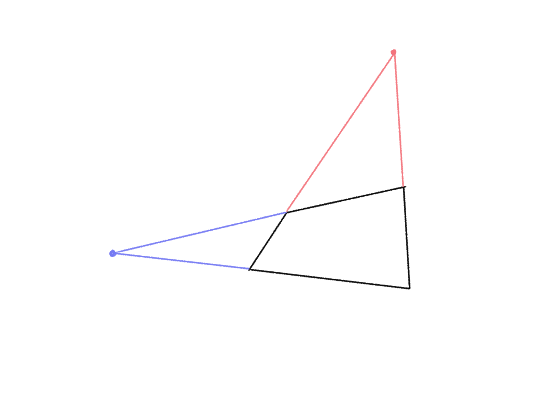

By extrapolating out its edges and finding where they meet, we can find out its vanishing points.

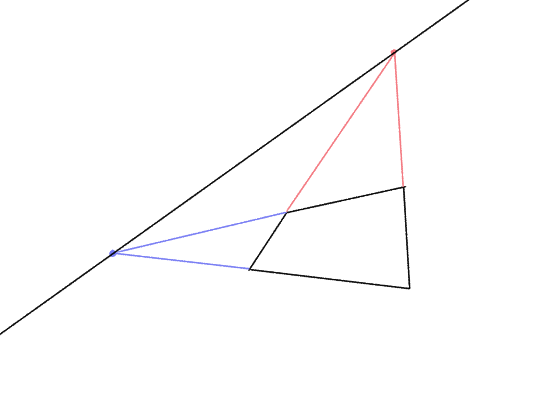

Now, if we connect them with a line, we’ve discovered this plane’s vanishing line.

Phew, that’s pretty steeply tilted - we’ve drawn a steep ramp! Since we started with a pretty distorted looking quadrilateral, naturally its vanishing points are pretty close together, meaning we have quite a wide-angle drawing here.

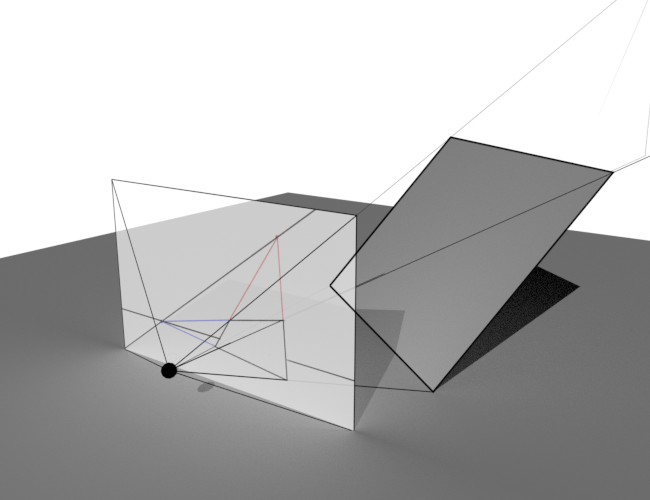

Just how wild angle? We can construct a 3D scene that matches a rectangle up with this perspective drawing in Blender, but there’s multiple ways to go about it depending on where we put the principal point. Here’s one possibility:

In this render, the field of view is a very wide 126°.

This render has a narrower field of view of 50°.

We’ll see what we can do with a horizon line in a moment, but let’s talk a little about what it represents.

Where a vanishing point picks out a set of parallel lines, a horizon line picks out a set of parallel planes. So if you have a stack of parallel planes, like a multistory car park, all of them have the same horizon line.

When two planes intersect, it creates a line in world space. Like all lines, this intersection line has a vanishing point in canvas space. This vanishing point is exactly where the vanishing lines of the two planes cross each other.

For example, suppose we add a ground plane to the drawing we just made, and we want this plane to touch the ramp we drew on its bottom edge. So the ground plane’s vanishing line should intersect the ramp’s vanishing line at the vanishing point of the ramp’s bottom edge.

Which is, in this case, the blue one.

Where does the vanishing line go in the picture?

A vanishing line represents a set of parallel planes, sure. But where do we place a vanishing line? How do we interpret its position and orientation?

Having a normal one (sorry)

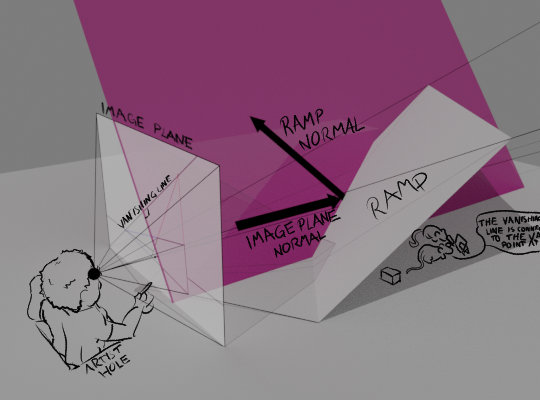

We’ve seen that vanishing points represent the direction of an eye laser, and they spread out from the central ‘normal direction’ to represent increasing angles. We can take this concept again, but first we need another geometrical concept: specifically, the normal of a plane.

The normal of a plane is the direction that is perpendicular to the plane—pointing away from the plane as directly as possible. We can draw a little arrow representing the normal at any position on the plane. Since all these arrows are parallel to each other, they have a certain vanishing point.

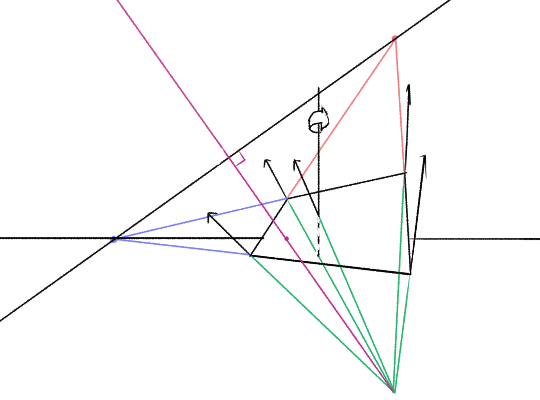

I found these normals with Blender, but we will see how you can do it without computer aid shortly.

So a plane has two features in canvas space: a vanishing line for the plane itself, and a vanishing point for the normal.

A funny little perpendicular construction

Now, bear with me—we’re about to make an odd little construction to illuminate how these points and lines fit together. Let’s draw a line (in canvas space), connecting the vanishing point of the normal to the principal point of our picture.

This new line we drew hits the vanishing line at a right angle!

Wait what the fuck?

This is a consequence of a theorem about vanishing points. If you have three orthogonal families of lines, they have three vanishing points. We can connect these vanishing points up to form a triangle. The orthocenter of this triangle is always the principal point. Fucked up.

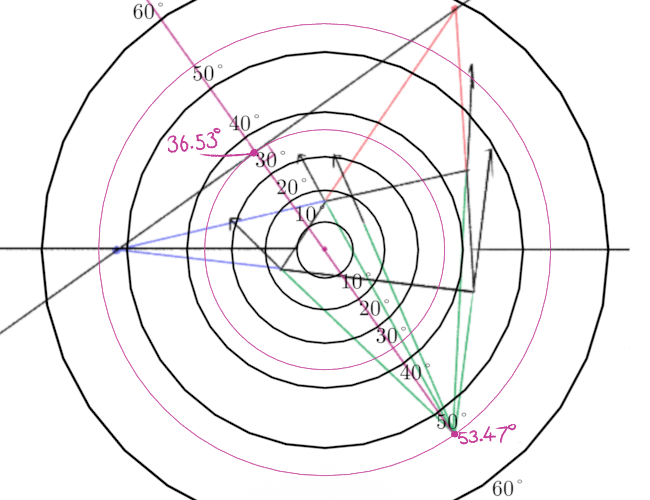

Incidentally, you might notice something surprising about the vanishing point of our normal (green), and the red vanishing point of the plane. They are vertically in line in canvas space! This caught be by surprise when I was rendering this picture. So why is this? In this case, it’s because we’ve aligned this plane so some of its edges are parallel to the ground plane in world space. So one of the vanishing points is on the horizon line. If you draw a line connecting this vanishing point to the principal point, the same theorem tells us that it must be perpendicular to the line through the other two vanishing points. So that line has to be vertical.

You might wonder—what exactly does this line represent in world space? Well, it can be taken to represent a plane defined by the normals of the plane we’re drawing and the image plane. We’re viewing this plane edge-on, so it just appears as a line. Like this:

Now, for the key point about this weird little construction. Remember all those circles representing angles we drew earlier? We can once again put these circles around the principal point, and look at the points we’ve just drawn. As before, we can use our circles to measure the angle between the lasers which hit those points.

The angle between them is 90°! This just follows from the facts that

- eye lasers (or visual rays if you’re getting tired of this joke) that pass through a specific vanishing point/line are parallel to the 3D object which vanishes there

- planes are perpendicular to their normals

So the eye laser to the normal vanishing point is parallel to the normal, an eye laser to the plane’s vanishing line is parallel to the plane, and so these two eye lasers must be perpendicular, i.e. the angle between them must be 90°.

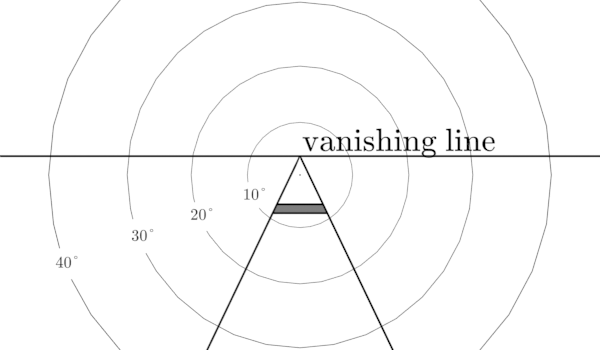

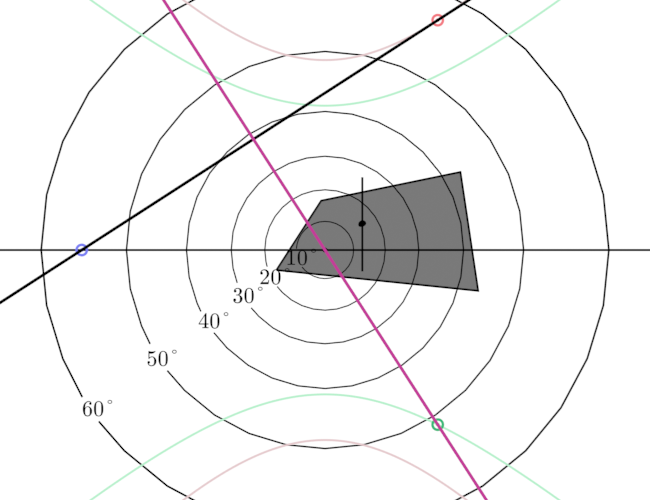

Armed with this weird construction, we can now understand what a vanishing line means. Let’s imagine that we’re staring through the principal point of the image. In this case:

- if a plane is facing us dead-on, it will not have a vanishing line. Or, in effect, its vanishing line is infinitely far away from the principal point.

- on the other hand, the vanishing point of its normal will be bang on the principal point.

- if we’re looking in a direction that’s parallel to a plane, its vanishing line will go through the principal point.

- the vanishing point of its normal will be infinitely far away, i.e. normals at any point on the plane will appear parallel in canvas space. For example, conventionally the normals to the ground plane point straight up, wherever we’re looking.

and the key point:

- as a plane rotates around an axis parallel to the image plane, going from parallel to our gaze to perpendicular to our gaze, its vanishing line moves from the principal point, out to infinity, and back again.

- the vanishing point of its normal does the opposite, following the plane’s vanishing line through the principal point

The esoteric alchemy segment

The following made sense to me when I first wrote it, but in retrospect I was too deep in the mysteries of perspective to really communicate effectively! It’s preserved for posterity, but at some point I intend to clean it up and give it a clearer treatment. For now, you will lose nothing if you skip on to the next article.

Get ready for a lot of confusing Blender gifs

A simple rotation

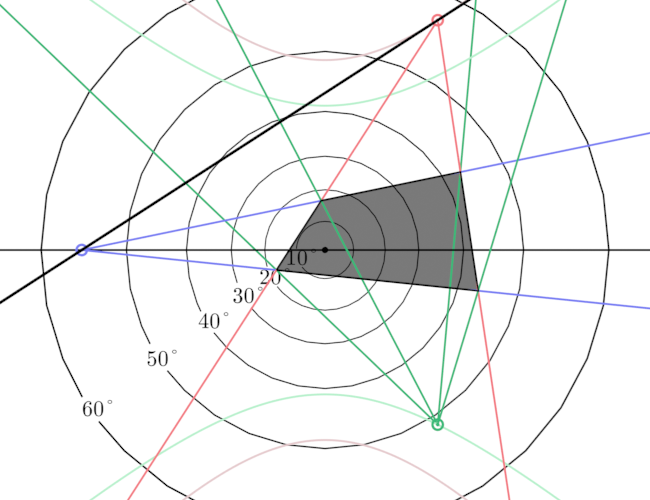

Let’s observe this with an animation! I’ve taken a rotating square which has, for simplicity’s sake, one pair of edges parallel to the image plane, so it only has at most one vanishing point.

Another simple rotation

Not every rotation will cause the vanishing line to move. If the rotation axis is perpendicular to the plane (parallel to the normal), then the plane’s vanishing points will simply move along the vanishing line.

A more complicated rotation

OK, that was comprehensible enough. I hope. Now we’re about to jump off the fucking deep end.

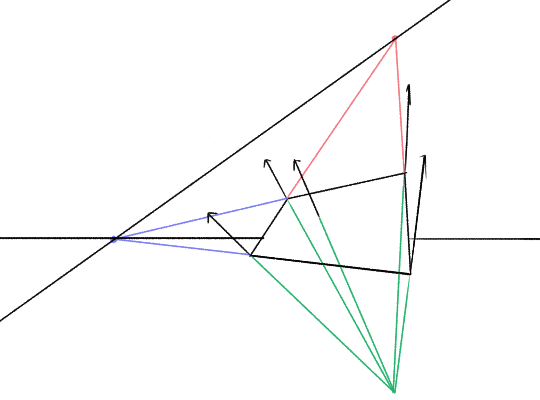

To investigate vanishing lines some more, let’s think about a more complicated rotation. Remember the ramp we drew earlier? Let’s spin it around the vertical axis, i.e. this axis:

The rotation axis is perpendicular to the ground plane, so the blue VP will move along the horizon line. What about the red vanishing point, and the green one representing the normal direction?

Well, this is what we end up with:

Look at that vanishing line dance! What the heck is going on there?

Here’s a few features we can spot in this image:

- the vanishing points that aren’t on the horizon line trace out hyperbolas. (You can prove this by working out where a ray with a particular pair of polar angles intersects the image plane, and compare the result with the parametric equation of a hyperbola. That’s kind of fiddly, and there may be a more elegant proof.)

- the vanishing line of the plane is tangent to the path of the red vanishing point. (what if it was instead following the green vanishing point? then the plane would be sloping in the opposite direction. but i’m not quite sure why this is)

- when the vanishing line goes through the centre of the plane, the plane itself disappears entirely into the vanishing line, much as we’d expect

- when one of the vanishing points of the plane gets infinitely far away, the vanishing line flattens out—in this case, parallel to the horizon line. This is basically the same case as the previous animation.

Now, let’s add in the purple line (the one that connects the principal point to the plane’s vanishing line)…

The point where this line crosses the vanishing line traces out a kind of figure-8 shape. It passes through the principal point each time our gaze is directly parallel to the plane. The ‘distance’ from the principal point is a measure how far our gaze is parallel to the plane, vs perpendicular to it.

What can you do with all this

Nice Blender animations and all, and maybe seeing these planes spin around will help build your intuition. Vanishing lines are going to be very useful in the next article, when we will use them to move things around while keeping their height consistent. But for now, let’s pull out some quick facts for roughly drawing inclined planes in perspective, assuming we have a horizon line:

- if we are looking directly ‘uphill’, the vanishing line is going to be parallel to the horizon. The steeper the incline, the further this line from the principal point.

- if we are looking ‘horizontally’ along the slope, the vanishing line is going to pass right through the principal point. The angle it makes with the horizon line is just the incline angle of the plane.

- anywhere inbetween we move gradually between these two extremes.

- if we’re looking uphill, the vanishing line will pass above the principal point

- if we’re looking downhill, the vanishing line will pass below the principal point

- the angle between the vanishing line and the horizon line will never be more than the incline angle of the plane, and will usually be less.

- the shortest distance between the vanishing line and the horizon line will never be more than the distance corresponding to the incline angle of the plane (as defined by our circles)

I know this article got pretty dense and heavy on the geometry, but that’s because I wanted to be sure to treat vanishing lines right, since people talk about them a lot less than vanishing points. Hopefully now we have a sense of what they mean!

In the next article, we’ll see how they’re useful. We have everything we need to start building our ‘bag of tricks’—methods we can use to make sure everything in a perspective drawing fits together at the appropriate sizes. If this article was confusing, it may be worth returning to once you’ve seeen the uses of a vanishing line…

Comments