originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/692959...

heeheehee, dick

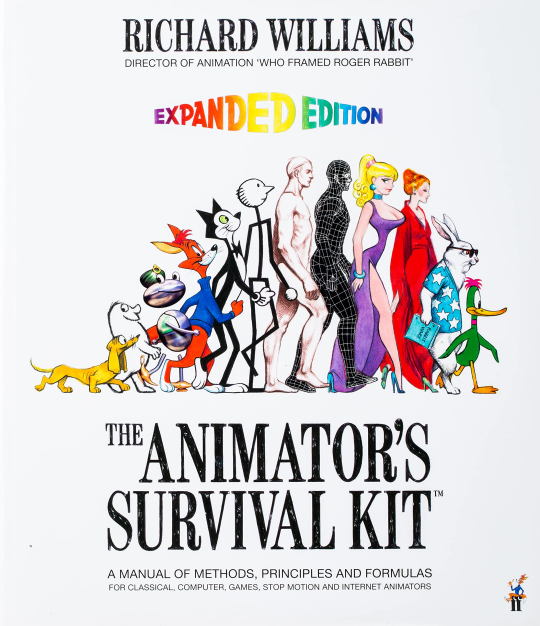

So. If you’re an animator, or have even thought about trying animation at some point in your life, you’ve probably ended up recommended a copy of this book…

Which is fair, it’s a fucking great book. It pretty much set the standard for animation pedagogy forever since.

You may also likely know the legend of its creator, Richard Williams. I believe I may even have mentioned him on Animation Night before, but since it’s been some time, let’s set the scene.

Animation is about compromise. On every production, from TV to film, you have to accept some limitation on your vision: drawings you don’t have time to correct, shots that might look better on 1s, CG where hand-drawn animation might look better. Part of the art of the animator is learning to do more with less, like developing a style that demands a more manageable drawing count.

Yet animators are proud creatures. It’s painful to let go of a sequence you know could be better with more time!

Which means… in the great annals of Animation Lore, there are a few times where some industry legend gets enough clout where they can get away with just going completely all out on a film. In the best cases, this results in films like Takeshi Koike’s Redline (Animation Night 19), which occupied Madhouse for a good seven years, but resulted in an exhilarating, one of a kind sakuga feast.

This one paid off, and while it rather strained the resources of Madhouse and they weren’t in a hurry to let Koike do whatever he wanted again, it’s clear that he levelled up a lot from the effort, with the nigh perfect understanding of 3D form becoming the foundation of his later Lupin films. But in these cases, actually finishing the film is maybe more of the exception than the rule…

The next famous case is that of Yuri Norstein - a titan of Soviet animation, who I have regrettably not yet covered on Animation Night! But Animation Obsessive have, in wonderful detail, so please go read what they have to say.

Norstein, famed for his films like Hedgehog in the Fog and Tale of Tales but fiercely independent, had a somewhat tense relationship with his superiors at Soyuzmutfilm. This came to a head when he set out to make an insanely ambitious feature-length adaptation of The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol. In 1985 he was fired from Soyuzmutfilm for working too slowly… but he found private investors after the fall of the Soviet Union… and has worked on it ever since, with an animation team consisting of just Yuri Norstein himself and his wife Francheska Yarbusova whose drawings form the cutouts which Norstein animates. Even now, 37 years later, he is still working on The Overcoat. Occasionally, clips surface.

It probably won’t be finished before Norstein dies, and at that point someone will probably find all the finished footage and edit it into something like a film. But the investors still seem to be willing to indulge him, perhaps because it’s not exactly expensive and it has the aura of a legend so they’re willing to play the long game.

But of course, the most famous of these quixotic passion projects is The Thief and the Cobbler, directed by Richard Williams. So let’s set the stage.

Richard Williams, in his own account, got interested in animation at age 10, in 1943, when he got a paperback book called How To Make Animated Cartoons. He started pursuing it seriously at age 22, while working as a painter in Spain, returning to London and working briefly in advertising while self-funding a short fim The Little Island, which he describes as a ‘half-hour philosophical argument’, released in 1958 when he was aged 25.

After making this film, Williams came to a very familiar realisation: he didn’t know nearly as much about animation as he had imagined. He describes watching Bambi for the second time and ‘crawling out of the theatre’ trying to figure out how they did that. He started idolising the animators at Disney and Warner Bros such as Ken Harris - someone he would one day work alongside, and become a close friend, and in the end be a pallbearer at his funeral. And The Animator’s Survival Kit‘s prose is still soaked in reverence for these animators, with a lot of cute little anecdotes about moments Williams spent with them.

His reverence for the Disney ‘full animation’ school was cemented after seeing the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine (Animation Night 86) and watching an unimpressed audience walk out - something Williams at the time attributed to the jerky animation that didn’t respect the movement principles of Disney. He describes by contrast how completely he was blown away by The Jungle Book, seeing the hand of some of the Nine Old Men like Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston - so he wrote them a letter about how much he was impressed and they invited him to come visit.

At this point his intro drifts away from autobiography, so let’s give a brief summary from other sources. During this time, Williams had founded a studio in London, which mostly made TV ads and animated segments for live action films such as the comedy Casino Royale (1967).

Notably also in this period, Williams animated segments for a film about the Crimean War, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968). The drawings for this sequence were insanely intricate, calling to mind the woodcut engraving style of newspaper illustrations contemporary with the war.

1971 saw his adaptation of A Christmas Carol, which was warmly received in the States. At this point he was frequently inviting talented animators from the States to come and teach the pathetic British how it’s done, including Grim Natwick (who is described as ‘still brilliant’ in the Survival Kit) and Ken Harris, who gets a fascinating little paragraph:

It takes time. I didn’t encounter Ken Harris until I was nearly forty and he was sixty-nine. I had to hire most of my teachers in order to learn from them.

I hired Ken in order to get below him and be his assistant, so I was both his director and his assistant. I don’t know if this is original, but I finally figured out to that to learn or to ‘understand’ I had to ‘stand under’ the one who knows in order to catch the drippings of his experience.

This period in the 60s and 70s was also the beginning of the saga that would lead, eventually, to The Thief and the Cobbler. Originally the film was to be titled Nasruddin, about the folk character Mullah Nasreddin. Williams had a hard time finding any sort of funding for the film, falling out with other production companies at times, so he quietly plugged away at it while working on other projects.

The Nasruddin connection runs a little deeper actually, because Williams was hired in 1976 to illustrate a collection of Mullah Nasreddin stories by the Sufi occultist writer Idries Shah. I’m not sure how this came about exactly - whether Williams went out of his way to draw Nasreddin, or if he happened to get hired by coincidence. In any case, the idea was clearly occupying a lot of his thought - but more on that anon.

The 70s also saw Williams work on animation for the title sequences for two of the Pink Panther movies, during which time he invited Art Babbitt to come to London to teach - Babbitt being the man who had been fired from Disney after the animators’ strike in the 40s, thus evading canonisation as one of the Nine Old Men. Babbitt also did some work on Thief and the Cobbler, and rendered this memorable quote about Williams:

He’s a director, designer, animator, and has a good layman’s knowledge of music. He’s a dreamer. He has more to learn as far as animation is concerned, but God, he can draw like a bastard

By this point, Williams would have been 42 years old. He was still making ads, despite ‘despising the form’, and making the occasional film or TV special such as Raggedy Ann & Andy (1977) and Ziggy’s Gift (1982).

Of course, the real point he became famous was when Who Framed Roger Rabbit came about. The strange Disney/Spielberg collaboration is actually one I’ve written about before, back on Animation Night 40, where I said some kinda mean things about old Dick. What I don’t really talk about there is what the film is about: yes, it’s about the animation industry and full of little injokes, but it is also to adult eyes recognisable as a parable for how San Francisco lost its public transport system, leaning on the idea of the auto-makers conspiring to destroy it. The real story may be a little more complicated, but having now seen the strip mall sprawl in both ends of California, I can see why people would come up with it. It’s grim out there.

I also didn’t talk much about the production. Williams was involved precisely because Spielberg saw footage of Thief and the Cobbler and was so impressed that he approached Williams.

By all accounts, working on Roger Rabbit was intense for everyone involved. Williams writes of drawing scenes late at night in the hotel room, and there was all sorts of goofy studio politics with neither Disney or Warner Bros wanting the film to favour one or the other (leading to situations like the piano scene where Donald and Daffy Duck were obliged to have exactly even screen time; the same goes for Bugs and Mickey.

It was also, I learned recently, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for one young James Baxter, then 20 years old studying animation but frustrated by the more experimental approach taken at his course, wanting to learn - like Williams himself - something more tied down like the Disney tradition. Traditionally animated films on the scale of Roger Rabbit are basically never made in the UK (and odds are, never will be again now CGI is king), so Baxter and some of his university friends dived for the chance.

Baxter joined the production as an inbetweener, working basically non stop on animation for that year (‘eat, sleep and animate’) but so impressed the Disney animators with a brief test he did of Thumper from Bambi that they gave him a few small scenes of feet and hands to animate. His success at this led to him getting more scenes, and this is where we get a little anecdote about Richard Williams (see, this is relevant!):

Baxter: Not being a seasoned animator, not being, y’know, knowing kind of the ropes of that, I did the classic junior animator mistake of going too far with something before you show your director or your supervisor, and I got the beatdown! I got the classic beatdown from Dick, which was great. I had gone way too far on like a shot of one of the weasels and, you know, he said ‘yeah yeah yeah! No, get the drawings, go get the drawings!’ So I had to stand behind Dick for an hour or so while he drew over my pencil drawings with a pen, one by one.

Interviewer: Ohh, wow.

Baxter: That’s kind of awesome. Not on a separate sheet of paper either, just like, my drawing, his pen.

Still, Roger Rabbit was completed on something like a schedule; the animation helped kick off the Disney Renaissance and now everyone wanted a piece of Dick. Off the back of that, Williams was able to negotiate a ‘negative pickup deal’ with Warner Bros: they would buy the film on a specified date for a specified price. Williams believed he could fund the film through a major studio, so rather than seek European arts funding, he went for the Warner Bros deal - a decision that would eventually be fatal to the project.

So at last the passion project, at this point already ‘in production’ for around 25 years starting in 1989, could really get underway. Thanks to the work done by the visiting animators, it represented the final film for a number of notable animators: Ken Harriss, Errol Le Cain, Emery Hawkins, Grim Natwick and Art Babbitt.

Williams’s approach was… utterly uncompromising. Sakugabooru commenter pkoduah provides a nice summary of the issues:

1. The film was led by animation rather than story. He thought of the most technically impressive animation scenes and then tried to shoe horn them into a story. If even half of the care that went into the animation went into the story and clear locked down storyboards it would had fared better and not been such a hydra. Even after the 2+ decades the story is still not fully resolved.

2. Richard Williams had an almost religious commitment to working on 1’s, even for relatively slow scenes. If he just changed that one thing he would have greatly increased his chances of meeting the deadlines.

3. The decision by a particular still powerful animation exec to steal his thunder with Aladdin which is heavily based on the Thief & Cobbler, put further pressure on the execs to take drastic measures with William’s glacially paced project.

We can also add that the story - with its goofy orientalist framing featuring jokes like Grand Vizier Zigzag and Princesss Yumyum, and an incredibly simple story that simply revolves around a macguffin - feels like a relic of a different era of animated film. Despite Williams’s disdain for it, it feels like it has a similar feeling to Yellow Submarine.

As an animator who’s tried it, the insistence on working on 1s is especially crazy to me. At first glance it sounds like twice as much work, because twice as many drawings, but it’s worse than this - because issues in an animation, inconsistences of shape and line, become much more obvious on 1s than they do on 3s or 2s where you can get away with larger changes of shape.

The modern worldview is quite different, incidentally. Lower framerates, when used properly, can also create a snappy, impactful feeling (c.f. the Kanada school, or Mitsuo Iso’s ‘full limited’). It requires a slightly different approach with stronger poses and a lot of drawing skill, since each frame is pulling more work, so a sequence designed to run on 1s will not look better with half its frames missing, but a sequence designed to run on 2s or 3s can look just as good.

In the Survival Kit, Williams briefly comments on the issue, saying in his entire career he’d basically only found one sequence that worked better on 2s for reasons he didn’t understand - to him, animating on 2s was purely a cost saving measure, and now he finally had the chance to do his passion project, he wasn’t going to accept anything less than the best possible.

But then, I think Williams’s motivation was less about appealing to audiences, and more about showing off to his art senpais - the great animators he idolised. It’s telling that one of the first anecdotes in the Survival Kit is about Williams and Ken Harris:

In 1967, I was able to bring Ken to England and my real education in animation articulation and performance started by working with him. I was pushing forty at the time, and, with a large successful studio in London, I had been animating for eighteen years, winning over one hundred international awards.

After seven or eight years of working closely with Ken, he said to me, ‘Hey Dick, you’re starting to draw those things in the right place.’

‘Yeah, I’m really learning it from you now, aren’t I?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘you know … you could be an animator.’

After the initial shock I realised he was right. Ken was the real McCoy whereas I was just doing a lot of fancy drawings in various styles which were functional but didn’t have the invisible ‘magic’ ingredients to make them really live and perform convincingly.

So I redoubled my efforts (mostly in mastering head and hand ‘accents’) and the next year Ken pronounced, ‘OK, you’re an animator.’

A couple of years after that, one day he said, ‘Hey, Dick, you could be a good animator.’

The anecdote continues with Williams going down to visit Harris in his trailer when Harris was aged 82, and finding that Harris could still correct his work. He still didn’t have Harris’s ‘thing’. But, at least, Harris said he ‘had his own thing going’.

It’s never mentioned explicitly, but the shadow of The Thief and the Cobbler hangs over the Animator’s Survival Kit. The footage that earned this praise from Ken Harris was footage from that film. By that logic, it should have been an immense success for Williams: finally earning him his place among the canon.

So why is it instead such a negative memory for Williams?

Well, in 1992, the film was still in progress, with just fifteen minutes left to complete - but it was too much for Warner Bros, who didn’t want to be seen as making a knockoff Aladdin. Williams was booted from his own passion project, putting Fred Calvert on to hastily fill in the gaps in the story and discard the unfinished sequences, adding a number of musical sequences with far lowre quality animation performed by a number of subcontractors including Sullivan Bluth Studios, Kroyer Films, Wang Film Productions/Thai Wang Film Productions in Taiwan and Thailand, Pacific Rim Animation in China and Varga Studio in Hungary. A second recut was performed by Miramax, removing even more of the original.

The resulting mess landed poorly in theaters, and Williams, utterly dejected for obvious reasons, shut down his animation studio and went back to Canada, spending the next few years as a teacher while nursing his wounds and starting work on writing what would become The Animator’s Survival Kit, published in 2002. And, in a sense, the story has a happy ending: Williams’s book became a bestseller, the reference on animation; Williams could pass on the secrets of the masters he revered, and trust that he would be remembered as a great teacher and animator.

In 2008 he was invited to become an artist in residence at Aardman; in 2010 he finished a film he’d begun in Ibiza in the 1950s titled Circus Drawings, and then he spent the rest of his life setting out alone on a new grand passion project, an adaptation of the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes. The first part of the film, titled simply Prologue, was released in 2015, featuring elaborate hand-drawn camera moves and background animation all done in pencils and photographed directly. You can watch it:

What of The Thief and the Cobbler? Well, the workprint of the film prior to the edits has survived, and the legend of it gradually spread across the industry. Williams showed his workprint in 2000 at the Annecy festival, impressing Roy E. Disney, who started on a project to restore and finish the film… but this fell through as Disney turned away from hand-drawn animation and Roy left the company.

Instead, the restoration effort was led unofficially by fans. A filmmaker Garrett Gilchrist, created the Recobbled Cut of the film, which used all the Williams-era footage that could be found from various sources, including unfinished pencil tests and scenes rotoscoped by Gilchrist to deal with dodgy footage, all edited to basically the structure of the workprint with some added music. As more and more people saw the Recobbled Cut, the film began to be rehabilitated, and Gilchrist created further revisions as more sources of original footage came to light.

So a good ending for Williams, right. But I’ve talked a lot about how it is made, what is the film itself actually like?

In its Recobbled form, The Thief and the Cobbler is very very obviously an animator’s passion project lmao. It’s full of Williams’s homages to Islamic art, with the stark geometric patterns creating some very clever shot compositions.

The actual story is very light on dialogue, and in contrast to Aladdin, it keeps its characterisations very simple. The thief and cobbler themselves are both basically mute, driven by very simple impulses: the cobbler is simple and well-meaning and enchanted by simple things, while the thief is single-mindedly determined to steal the Golden Balls, never mind the consequences. It’s not a surprise it didn’t land well in a time when the rule in animation was Don Bluth and the Disney Renaissance: there are no ‘I want’ songs or really, character arcs as such.

So the Cobbler gets with Princess Yumyum, but… like a fairytale or a Golden Age disney film, not because we’ve been sold on them as characters who have chemistry and want to get with each other, but more because Yumyum seems to find the Cobbler kind of… a weirdly endearing little pet and that’s what the plot demands. The Thief continues his thieving throughout. Late in the movie, a massive army of barbarians shows up out of almost nowhere, leading to a spectacular scene in the cogs of their giant war machine, but we aren’t really asked to believe in them as a culture. It is basically a series of setpieces loosely strung together.

I have said in the past that The Thief and the Cobbler is callous in the treatment of the historical Islamic culture it depicts. It is certainly an Orientalist film and certainly very British in its outlook, there’s no question of that. Still, while I do still think the joke names like Vizier Zigzag and Princess Yumyum are tasteless, I think it would be hard to say that Williams does not have reverence or devotion. It’s a different beast than Aladdin - the way he shows this devotion is through his mad, obsessive craft. I’m not quite sure how I’d feel about it if I was on the receiving end of it, mind you. (I would be quite curious to find out what the Arabic dub does with it, if there is one.)

The thing is that Williams is, far more than a director, an animator. Like, say, Masaaki Yuasa, he loved the medium of animation more than anything - no matter what he’s animating, he’s clearly beyond happy if he can make it move in a cool way. The Animator’s Survival Kit is intoxicating because he really sells you in this fascination with how things move - the nuances of a walk, the effects of timing and spacing and gesture, like what does happen if you make this frame go up and this frame go down? The previous generation of animators was his god, but he also was keen to experiment, find new possibilities. For this reason, Williams is still relevant. Even if he had… fascinatingly strange ideas about how gay people walk!

But this means, unfortunately for this film, that he was far, far more of an animator than he was a director. In fact this ends up a very endearing quality. The Thief and the Cobbler is an intensely idiosyncratic film, a true expression of the worldview of Richard Williams both good and bad… the workaholic maniac that he was, a man with something to prove.

And for a man with a great deal to say about acting, we should look at the acting in this film. Since many scenes are wordless, it falls to the acting to convey the emotions of the characters in the scene. And… they’re certainly not subtle, but they are creative, full of clever and surprising images. It is I suppose a very theatrical mode of acting: a lot of exaggeration and big movements.

On the other hand, the characters’ inner worlds are like… well they aren’t really there. Pretty much everything is right there on the surface. Everyone is really exactly what you see. It’s interesting to contrast this with the psychological turn soon to be taken by anime in the 90s, in Eva or films like those of Mamoru Oshii. A character like Motoko Kusanagi has incredibly graceful 3D movement, yet she barely emotes… and nevertheless through the framing and script, we know a lot about what she might be feeling. Shinji sits still listening to his tape player. Sometimes less can be more.

What of the Thief? He is the most enigmatic character in the film, and yet he too is not complex. We don’t know why he wants the Golden Balls, why he tolerates flies buzzing around him, but he surely does. He’s just a weird little slinky gremlin guy, and in the end he gets away.

Of course, Williams talks a fair bit about gender in his presentations on animation acting. The Animator’s Survival Kit bonus DVD includes videos of lectures, so here’s a clip someone uploaded of some examples of what he’d say:

You can see how his interest here is in really pushing and exaggerating that gender difference - of course, pushed to extremes for pedagogical purposes, but still, it says something about the worldview he was operating under. Especially at the end when he gets a laugh by, essentially, animating a very effeminate walk for the bodybuilder character.

So a character like ‘Princess Yumyum’ is exactly what she appears: curious, vulnerable etc., a feminine ideal. There is little room for contradiction, or even straining against the bounds of this role like Princess Arete. The same is true in a lot of Williams films. Animation is about exaggeration, of course, but Williams was inescapably a man born in the 30s.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn from him. Learn a lot, really. Thanks to Wiliams, even though the renowned animators of Disney and Warner Brothers have died, we can get a sense of how they used to think about things, and build on them. We can understand the tricks of spacing he uses to create a sense of impact, and pick up on some of his observations and insights about acting. And certainly, his exhortation to do figure drawing has caught on in a big way since the book has been published.

I feel like, in many ways, I can see myself in the young Richard Williams - well, not nearly as accomplished, but the awe he feels towards those old Disney animators, I feel towards people like Weilin Zhang, Mitsuo Iso, Shinya Ohira, James Baxter… the ‘how can they do that’, but also, one very important line:

Irrepressible ambition made me change my opinion that they alone could attain such heights; I figured, I think correctly, that given talent, experience, persistence - plus the knowledge of the experts - why should everything not be possible?

I couldn’t stand it any more. I had to know everything about the medium and master all aspects of it. Cap in hand, I made yearly visits to Milt and Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston and Ken Anderson at Disney.

For my part, I joined a lot of animation discord servers and now, starting this month, I’m trying to hit that “James Baxter’s first year” sort of pace. We’ll see how it goes. [editor's note from the future: it didn't go so well lol] But like… all these guys are human. My muscles aren’t any different than theirs - I just need to see if i can shape my brain to acquire that power of observation and intuition for drawing. The method is clear enough. Like Williams, I won’t be an exact clone of my idols - I’ll become my own thing. If I just keep at it.

Anyway, I have gotten over my reluctance to screen The Thief and the Cobbler - orientalist as it may be, it is an important movie to animation history, and one worth seeing again, as well as Williams’s earlier animations to see where he came from. So if you fancy joining me, we’ll be at Twitch tonight - please head to twitch.tv/canmom and we’ll begin the movies in 15-20 minutes probably!!

Comments