originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/699945...

Note: I make some mistakes below when describing the plots of the movies in question. This article is due an update!

Oh that Hayao Miyazaki! We sure have a slightly complicated relationship to him here on Animation Night!

See for example…

- Animation Night 70, where I talk about his early career and years as a Toei union man, up to the founding of Ghibli;

- Animation Night 100 where I tell you about one of my favourite ever films Mononoke-Hime;

- Animation Night 111 where we look at the fascinating My Neighbour Totoro-Grave of the Fireflies double bill of 1988.

Tonight, we’re going to look at two films, Porco Rosso and the controversial The Wind Rises, which indicate his particular arc through life in, honestly, a rather sad way. Putting them alongside each other to see what we learn…

If there’s one thing old Hayao loves, it is aeroplanes - particularly planes from the early-mid 20th century. No surprise, really: his dad Katsuji Miyazaki ran a company Miyazaki Airplane, which manufactured parts for world war II aeroplanes such as the infamous Zero fighter plane. (Put a pin in that one!) Despite working to arm the Imperial Japanese military, Katsuji was able to get out of actually serving in the war by telling his commanding officer that he didn’t want to fight when he had a wife and kid, which somehow got him discharged with just a lecture.

The young Hayao, born 1941, was therefore surrounded by planes, which were the source of his family’s comfort. He spent his earliest years fleeing from American air raids, suffering from digestive problems, and watching his stern, intellectual mother Yoshiko suffering from spinal tuberculosis (though she ultimately made it to 1983, at age 72). At school in the 50s, he took an interest in manga - which in those days naturally meant Osamu Tezuka; he also went to see drama films with Katsuji such as Meshi (1951).

In ‘58, he saw Toei’s Legend of the White Snake (白蛇伝 Hakujaden), notable as the first colour anime film, sneaking out from studying for his exams. The film had a profound effect on him. In Starting Point, he writes that he fell in love with the film’s heroine Bai-Niang, and yet gradually started to imagine how he might have done the film differently to better show the secondary characters.

Hayao went to university to study political economy with a focus on ‘Japanese Industrial Theory’, and at the same time, started drawing in earnest, cranking out thousands of pages of manga and spending a lot of time sketching and chatting politics with his middle school art teacher. The 60s and 70s were a high point of left-wing activity in Japan, the time of the Japanese New Left and the Anpo protests against the US-Japan security treaty (c.f. Toku Tuesday 33 on Nagisa Ōshima for a truly fascinating filmmaker who rose to prominence at this time!) So Miyazaki fairly naturally became a Marxist, and stayed such as he got his start working in animation, which I’ve covered in other posts.

So at this point perhaps we can see the curious contradiction that sits in so much of Miyazaki’s work: he genuinely loves aeroplanes and other kinds of military hardware on a kind of aesthetic level, and yet this sits pretty curiously against a worldview that went from Marxist to environmentalist and has no love of war or nationalism.

With all this in mind, let’s take a look at a few of Miyazaki’s early depictions of planes. First would be his work on episode 21 of Moomin (1969), by TMS entertainment. On this infamous episode, Miyazaki’s senpai Yasuo Otsuka called in his protégé to handle of all things a battle scene with planes and tanks - one which infuriated Tove Jansson, already dissatisfied with the tone of the adaptation, to the point that she pulled the show out of TMS Entertainment and A-Pro’s hands and gave it to Tezuka’s rival studio Mushi Pro instead.

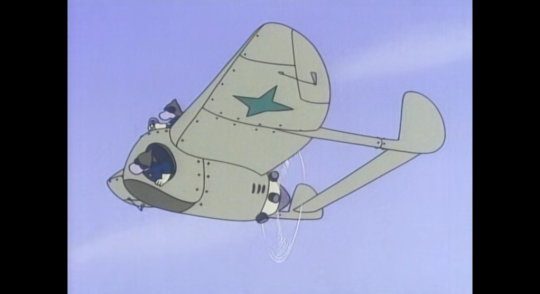

This did not deter Miyazaki at all. In his work on ‘Green Jacket’ Lupin III Part I, which he co-directed with Takahata and Masaaki Ōsumi as well as animating several scenes, we start to see his love of mechanical detail shine through once more. Miyazaki’s plane obsession would shine through even more strongly with his direction of two episodes of ‘red jacket’ Lupin III Part II (1980), under the pen name “Tsutomu Teruki”, directing animators like the spectacular Kazuhide Tomonaga as @kbnet documents here. By that point his style had matured - the character designs and motion feel like something drawn in Ghibli’s early years, and the plane backgrounds are astonishingly dense with detail. The Castle of Cagliostro is by comparison relatively light on aeroplanes, but truly elevates Lupin’s car to a character - not to mention the film’s ridiculously elaborate finale where the characters battle through an enormous system of gears.

In between these two Lupin jackets came Future Boy Conan, where we start to see Miyazaki find more things to say about planes than “damn cool!”; a full of wonderful plane adventures, yet they also represent the sinister forces of industrialism which destroyed the world once and threaten to do it again.

In an essay from 1979 that opens the collection Starting Point, Miyazaki remarks on the qualities needed to animate a plane on Conan, giving a sense of his philosophy around animated machines - and his perfectionism:

Quite a few of toda’s younger animators plunged directly into this line of work because they were fans. But if I were to ask them to draw a picture of what they think a chaika (a flying boat in Future Boy Conan) would look like in flight, they would only be able to imagine what they had previously seen on past TV anime shows. And I wouldn’t be able to use their work as a result.

To draw a chaika flying in a truly original fashion, you would need to have read at least one book on the history of flying, and then be able to use your imagination to augment what you have read.

This is followed by an anecdote about Russian pilot, and builder of the first four-engine biplane, Igor Sikorsky - the man who for Miyazaki “symbolises the way men really fly”.

Miyazaki of 1979 seemed to have a lot on his mind about the relationship of humans to machines. He criticises the mecha shows of the time for a lack of focus on how the character creates and maintains the machine: “the protagonist should struggle to build his own machine, he should fix it when it breaks down, and he should have to operate it himself”. And true to form, when Miyazaki’s films portray machines, there is as much loving depiction of the maintenance as the actual machines in flight.

We’ll fast forward now, since I talked quite a bit about The Castle of Cagliostro, Nausicaa and Castle in the Sky back on AN 70, and Totoro back on AN 111. I haven’t covered Kiki’s Delivery Service yet, although you can trust we will before too long! No, the first film of interest to us tonight is a bit of an oddball in the Ghibli oeuvre; well known to fans of the studio but not quite as much of a household name. That’s Miyazaki’s flying pig movie, Porco Rosso (紅の豚 Kurei no Buta).

^ here’s your obligatory Yoshinori Kanada-animated background animation scene!

Porco Rosso is Miyazaki’s first movie to not just feature planes, but be truly overwhelmingly about planes. Set in a vaguely Mediterranean world, it expresses Miyazaki’s nostalgia for a lost era of flying before he was born, and yet it’s also tinged with the impending horror of the second world war and the recognition that the planes that Miyazaki loves so much are above all weapons.

Unlike many of Miyazaki’s movies, it centres on mostly adult characters and its narrative arc doesn’t really move to any sort of definite resolution; it’s more a portrait of the era, or rather, Miyazaki’s fantastical imagination of the era, in which there can be sky pirate families flying with dozens of children and, of course, a man can get transformed into a pig. The central character of the film, the eponymous Porco Rosso (so called because he’s a pig (porco) that flies a red (rosso) aeroplane), is an outcast due to his pig curse, but also perhaps because he insists on flying for himself rather than for the Italian military, a stance that is already becoming obsolete.

So Porco ends up adopting a young aircraft engineer - a bishōjo character in the spirit of The Castle of Cagliostro - who is eager to see the world. The largest conflict in the film is Porco butting heads with an arrogant American pilot over the affections of Gina, a woman who runs a bar for pilots - yet the two are clearly more similar than different.

By this point Studio Ghibli is well-established, and Miyazaki can take his pick from some of the best animators in the entire industry. So we see not just Yoshinori Kanada, but also sakuga aces Mitsuo Iso(!!!) and Shinya Ohira(!!!), and with Ghibli money they can truly go all-out. All that attention to mechanical detail, the buliding of machines, is there. Events like the testing of an aeroplane engine are accompanied by incredibly complex multi-layered shots that only a drawing demon like Ohira could accomplish. Only someone whose grasp of 3D form is as precise as Mitsuo Iso could animate some of these shots of subtle wobbles in the pre-CGI era. And on top of that, the colour design of Michyo Yasuda is there in all its beauty, Joe Hisaishi truly came into his own with a score as wistful and nostalgic as such a film demands; it’s an incredibly accomplished work of animation.

But, planes though.

One of the film’s most memorable scenes - one which unites the two films we’re going to see tonight - sees Porco fly up high into the sky to a kind of flying graveyard of aeroplane pilots. It’s here we especially see the ambivalence that obsesses Miyazaki: he finds aeroplanes one of the most beautiful things in the world, idolises their pilots, and yet of course this period of aviation was an incredibly dangerous one, and moreover the aeroplane development was catalysed by war and soon would lead to a level of destruction never seen before in human history with the bombing campaigns of the second world war.

It would be natural to imagine that the workshop where Porco recruits Fio may in some way resemble the workshop run by Miyazaki’s parents - in spirit, as he imagines it, if not in detail. Like Miyazaki Airplane, this workshop in Italy cannot be doing anything but supplying aeroplanes to Mussolini, and indeed we see Porco utter one of the most quoted lines in the film when he tells his old air force buddy “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist.” even though this leaves him essentially a fugitive, on his own with a plane and a girl (like half his age I guess?).

^ This swarm of tadpole-like children was animated by Masashi Ando.

If you actually read Miyazaki’s comments about his dad, it seems a little different. Far from being lovingly crafted, Miyazaki writes, Katsuji would make defective parts and bribe officials to look the other way. He would go to nightclubs right into his 70s and ask Hayao if he’d started smoking yet.

At the time this film came out, Hayao Miyazaki’s father Katsuji would die only a couple of years later, in 1993. We can find a short piece that Hayao wrote about it in Starting Point (page 208-209, My Old Man’s Back):

…And after the war, he had no sense of guilt about having been involved in the military arms industry or having produced defective parts. In effect, for him war was something that only idiots engaged in. If we were going to war anyway, he was going to make money off of it. He had absolutely no interest in just causes or the fate of the state. For him the only concern was how his family would survive.

(…)

When he died two years ago, those of us who gathered together agreed that he had never once said anything particularly lofty or inspiring. If I have one regret, it is that I never discussed things seriously with my old man. From the time I was young, I always looked at him as a negative example. But it seems, after all, that I am like him. I have inherited my old man’s anarchistic feelings and his lack of concern about embracing contradictions.

So the actual reality of aeroplanes around Miyazaki had little to do with the romantic images we see in his films. But that ‘lack of concern about embracing contradictions’ seems important…

In 2013, 20 years after Katsuji’s death, Miyazaki would direct a new film, The Wind Rises (風立ちぬ Kaze Tachinu, lit. The Wind Has Written) - to date, his last film, although of course like clockwork he’s since come out of retirement to work on another one. Ostensibly, this film is a biopic of Jiro Horikoshi, the inventor of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane so vital to the Imperial Japanese war machine.

However, if you look into the details, you soon realise that the story present in the film - particularly its central element of Jiro love interest and eventual wife Naoko Satomi - is a complete fiction. Jiro Horikoshi did marry and eventually had five children, but there is very little information about them, even in Horikoshi’s own autobiography. An article comparing the film against it remarks…

The Story of the Zero Fighter is 80% plane design ideas, measurements and stories surrounding Jiro’s career. There’s so much focus on the construction of the planes there’s a measly 20% left for autobiographical material.

According to that article, Horikoshi’s autobiography describes his initial thrill at reports of the Zero’s success in the invasion of China, then later, the psychological impact of a bomb striking nearby and his gradual realisation of what a war actually meant. It’s an arc towards increasing horror at the measures the Japanese Empire was taking to win the war with it, particularly the announcement of the Kamikaze suicide-bomber tactic:

Jiro was approached by the press to write a short essay on the Kamikaze, but he declined. He found it too emotionally difficult to think when he looked at photographs of smiling pilots boarding Zero’s, knowing they were doomed to death. Sobbing, the only sentiment that encouraged him to put pen to paper was dedicating his writings to the families who had lost their loved ones in the war. In the haunted depths of his mind he wondered why Japan had not just given up the war, and why they had gone to such measures with the Zero’s.

Very little of this arc makes it into The Wind Rises. Nationalism is glimpsed only at the margins. In one trip to Weimar Germany, Horikoshi witnesses a Jewish man being pursued; later, he meats a privately anti-Nazi German man at the hospital who talks briefly about how foolish nationalism will make a country ‘blow up’, and his final oblique conversation with the dream-ghost of his idol, Italian aircraft engineer Giovanni Cabroni, about what it means to build planes when they will be tragically be destroyed.

Instead, we find Miyazaki draw in a different source for the primary character arc of this movie: a novel by Tatsuo Hori that also has the title 風立ちぬ Kaze Tachinu. Set in a sanitarium much like the one in which Horikoshi spends the latter half of the film, it tells the story of the relationship between a nameless protagonist and a woman dying of tuberculosis.

It seems an odd connection at a glance: why would you take this seemingly entirely unrelated novel and apply it to an actual historical person? To me, the most plausible answer is that this isn’t really a film about Jiro Horikoshi. Because recall that, of Miyazaki’s parents, his mother also had spinal tuberculosis, and his dad also made planes for the war. Yet, the Horikoshi of this film hardly resembles Katsuji Miyazaki either, who we’ve seen was far from a workaholic like the film’s Jori Horikoshi. Instead, this would better resemble Hayao himself. So instead, it seems to be using this historical setting as a kind of place to explore Miyazaki’s feelings about his parents, his own craft in animation (wedded to the technical industrial world as it is)…

Inevitably that’s a pretty fraught thing to do! More so than any of Miyazaki’s other films, the film sparked a lot of controversy, mostly for how it handles the topic of the war. You could argue that like, OK, do you need a movie to moralistically lecture you on how invading most of Asia was bad? Must it rub our faces in the atrocities committed by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy to be a worthwhile movie?

One answer is that with the amount of modern nationalism and historical revisionism out there, it might not go amiss for national hero Hayao Miyazaki to take a stand there! But honestly it’s more that, with such subject matter, seems to go out of its way to avoid showing what the Zero was actually used for. The main tragedy, as far as Horikoshi was concerned, seems to be that so many pilots of this beautiful aeroplane die; that his pursuit of engineering beauty was corrupted by worldly matters like a war.

Which isn’t necessarily a completely inaccurate portrait of the real Jori Horikoshi’s attitude to his creation. The quote that inspired the film was “All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful.” But then this film goes out of its way to emphasise Horikoshi as a caring family man, a wholly sympathetic character, when to much of the world, Jiro Hirokoshi is a symbol of….

That. (And that’s the low estimate. It could easily be four times higher.)

But let’s look at how it relates to old Hayao and the contradictions he talks about living. If not to the same degree as old Isao Takahata, Miyazaki is an infamously exacting and demanding boss, heavily correcting nearly every cut that passes his desk. He’s spent his life working at a frankly kind of insane pace and expects his employees to keep up. Studio Ghibli has at least one dead body on its hands. Yet if you look at his films, they’re all about freedom and romanticism and the importance of enjoying nature. In Totoro, the dad is pulled away from his desk to play outside by his children. Probably not a good idea at Ghibli.

Then there are all the family relationships, all the way from the panda in Panda Kopanda to the mother in Ponyo. But Hayao Miyazaki was a distant father (he writes in Starting Point that his children were basically raised by their mother), and infamously callous to his son Gorō when he attempted to direct a film that Hayao didn’t think he was ready to handle.

Can we analogise animation to an aeroplane? It is beautiful in much the same way as an aeroplane is: elegant shapes, the technical coordination of many disparate parts to achieve an effect that would perhaps otherwise sound far-fetched (a flying machine? a picture that moves?). What’s the cost of animation? Well, thankfully nothing comparable to killing millions of people. But it is not a light undertaking. It is something that does eat lives. Is that a comparison that Miyazaki would have had in mind? I doubt it, honestly, but it’s what occurs to me faced with this film.

Thus I read the film’s Jori Horikoshi is a strange emotional blend of Hayao Miyazaki himself, an idealisation of his father or perhaps the sort of man he wishes his father was, and the real man who invented an effective fighter plane which helped enable his country to pillage most of Asia. And the rest of us? Well, the person working through these contradictions is Hayao Miyazaki, at the head of one of the highest concentrations of skilled animators the world has ever seen, so it’s going to be shared with nearly everyone. Would it probably have made more sense to do this in something like a manga, instead of a high profile movie? …Well, I think so. But that’s not what happened, so we have this movie.

Inevitably for a late Ghibli movie, this film is crazy good looking. No Yoshinori Kanada anymore since he died in 2009, but Shinya Ohira is still alive, and he is absolutely capable of handling a Kanada-like background animation sequence. One of the most breathtaking sequences is the portrayal of the Great Kantō Earthquake by Atsuko Tanaka and Taichi Furumata, which combines both brilliant multiplane shots and unbelievably complex full background animation scenes of waves rippling through houses and streets. Tanaka also handled these mindblowing shots of cloth flowing in the wind as Naoko paints that form the film’s major recurring image.

The film uses slightly more digital compositing effects than the 90s pre-digital Ghibli films. For the most part the colours are just as lush as those older films, and there’s even very effective use of CG with handpainted textures now and then; Ghibli weathered the transition to digital a lot better than many studios.

And yet, despite all of this, it is a movie that leaves me feeling pretty unsatisfied, like a lot of late Ghibli movies. Hayao Miyazaki has said that he’s attempted to move away from familiar kishōtenketsu structures and try something novel, but when I watch films like Howl’s Moving Castle, I’m left wondering like… what did all of that amount to, in the end? For all its spectacle, what is this film even saying that Porco Rosso didn’t say… honestly, say better?

Maybe I’ll find an answer on a rewatch. It’s… far later than I planned to start, but if you’re willing to join me, please hop into twitch.tv/canmom and we’ll watch Hayao Miyazaki’s two big films about planes! And I’ll show you the Moomin thing too.

Comments