originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/706270...

Hi friends welcome back to Animation Night! It’s the night where I screen animations on Twitch and sometimes you come and watch them.

Contents

Contents

Introduction

Last week we shone the Animation Night beam on Hiroyuki Okiura, and I was surprised by how great his film A Letter to Momo turned out to be. The plan had been that on Tuesday I’d bring back the other film night, ‘Toku Tuesday’, in order to watch Mamoru Oshii’s Kerberos film trilogy, leading into the third entry being Hiroyuki Okiura’s film Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade. I did that, but I had to end the night early after only one film. So, it’s rolled over into Animation Night this week.

But that’s an opportunity in a way, because this gives us a chance to dig up a fascinating Oshii obscurity. More on that in a minute!

That film we watched on Tuesday was The Red Spectacles, and it was fucking fascinating. Going into Kerberos by reputation I expected some kind of philosophical meditation on power and an alternate history setting, but this was something a lot stranger. I wrote a more detailed commentary on it here, but to my reading, this surreal film is essentially there to probe the warped fantasy of a self-important fascist who’s terrified of betrayal, when he’s much more of a traitor than any of them. However, as an introduction, it doesn’t really tell much more about the broader Kerberos story, beyond the fanaticism of the organisation’s members.

The actual event we learn about is: Kōichi, high-ranking member of the heavily armed paramilitary police organisation ‘Kerberos’, slunk away with a suit of power armour when the state dissolved the organisation. Later he came back to Japan, and was promptly killed.

It’s followed by prequel StrayDog: Kerberos Panzer Cop, which is a more literal film, following another Kerberos member who goes looking for Kōichi in the Phillipines. Although this is not at all animated, I am going to show it tonight regardless. We’ve shown an animated OVA on Toku Tuesday before, you can allow me one (1) live action film, as context for one of the most renowned animated films of the 90s. I think it’s worth showing what Okiura was building on when we get to his film, particularly since this film establishes even more the gruesome image of Kerberos suits in action.

About Jin-Roh, I don’t have much more to say beyond what I said last week, so here’s a slightly revised version of that.

The person chosen to be the director of Jin-Roh in Oshii’s stead ended up being ‘allergic to computers’ Okiura, judged the most promising of the studio’s younger generation and eager to direct a serious drama film. Though Oshii wrote the original script, Okiura made many decisions that Oshii wouldn’t; his take on the story put a bit more emphasis on the romantic relationship, and he ambitiously decided to do a film with no CGI whatsoever at a sprawling 80,000 cels, punishingly realistic designs and understated action, and all sorts of complex technical crowd shots.

By all accounts, he succeeded. His film is heavily in an Oshii idiom: very slow and contemplative, morally ambiguous, set in the near future, about cops. Its story tells of a member of a counter-terrorism unit in the context of widespread protests. Power-armoured Kerberos are sent as ‘counter-terrorists’ to suppress the protests, which becomes a massacre as they turn their machine guns on the crowd. The story follows Kazuki Fuse, who decides not to gun a girl only for her to set off a suicide bomb, disgracing him in the eyes of his unit.

Later, wracked with guilt, he encounters a woman called Kei who claims to be the suicide bomber’s sister. Kazuki makes a connection with her, not knowing at first that she is also a bomb courier like the girl he shot, or the broader context of infighting between Kerberos and their rival Public Security that brought them together.

To spoil the ending, Kazuki becomes increasingly attracted to Kei, while dreaming feverishly about shooting her in the sewers as he was supposed to shoot the suicide bomber. He and Kei become involved with a conspiracy within Kerberos, the ‘Wolf Brigade’, which succeeds in assassinating their enemies in Public Security - but then at the end Kazuki is ordered to shoot Kei and he declares himself a ‘wolf’, dedicated himself wholly to Kerberos.

I found this rather academic video on Youtube, which talk in some detail about how the film invokes the metaphor of Little Red Riding Hood in characterising Kazuki:

To Pause and Select’s telling, Jin-Roh is at pains to complicate the simple wolf/victim dichotomy of Little Red Riding Hood. From a ‘having faced lines of cops at a street protest’ POV, I’m not sure how that will come across really, and I think it’s possible I’ll reach some kind of divergent reading.

The background to Jin-Roh is the social movements I’ve talked about occasionally on here before. To put it briefly, Oshii (much like Oshima, and to a certain extent Miyazaki) was apparently involved the second wave Anpo protests in 1970 against renewing the treaty that allows the US to maintain bases on Japanese soil. In the 50s, the US had used Japanese infrastructure to carry out the Korean War, to significant profit of many people in Japan, and their military presence was pretty significance. The movement - popular in particular with leftist students - wanted Japan to have a more neutral role in the Cold War. The government’s efforts to push through a continuation of the treaty led to major clashes with police in the 60s; a second wave of protests in 1970, following the student riots of 68-69, were less disruptive and completely ignored by the government.

As for Oshii’s role in all this? I’m not sure; I downloaded the book Stray Dog of Anime that Wikipedia uses as a source and it’s kind of vague.

In any case, the ‘60s movement was a major failure, and the student movement fell into infighting and recrimination that later gave rise to the New Left. (This is portrayed in films like Ōshima’s Night and Fog in Japan). In the aftermath, the Japanese left took some weird turns, like Yodogō Hijacking Incident, and tragic ones, like the Asama-Sansō Incident (watch as Bryn reels off her list of ‘weird things that happened in Japan in the 70s’ again…); it otherwise became increasingly sidelined during the economic boom of the 80s. You can see the shadow of all these events in films like Akira (AN34); by the time of Jin-Roh, they were now distant history.

Okiura, born 1966, would have been way too young to have seen these protests. The protest scenes, drawn by (who else could it be?) Toshiyuki Inoue, are nevertheless striking encapsulations of the tension of a crowd facing down a police line. As Pause and Select’s video noted, the police are actually on the back foot here, cowering behind their shields under a barrage of projectiles. In the world of Jin-Roh, the conflict has escalated considerably beyond the Anpo protests, to the edge of civil war. So they decide to escalate to military levels of force.

The colour palette of Jin-Roh is very muted, greys and browns everywhere; the acting is generally kept very grounded, the proportions of the characters are only barely stylised. Very ‘Production I.G.’ in other words. That kind of approach raises the question of ‘why not do it in live action’. For someone who loves traditional animation for its own sake the look of this film is answer in itself, but you could answer that in various ways beyond simple practicality (it is difficult to draw an enormous crowd but expensive to close off a street and shoot a scene involving a large crowd and pyrotechnics). One might be that later there was a Korean live action remake of Jin-Roh and it wasn’t very good. But why? Perhaps it is that there is a certain abstracting effect of animation that turns its characters, no matter how realist they are drawn, into symbols, and this is a story that constantly compares its characters to archetypes in a fable. I might have more of an answer later.

Anyway, I mentioned another Oshii oddity, and that is Tachiguishi-Retsuden (立喰師列伝); you could kind of break down that title very literally as ‘Biographies of the Stand-up Eating Masters’, but the official English translation is Tachigui: The Amazing Lives of the Fast Food Grifters. If you remember those noodle bar scenes in The Red Spectacles, this expands on that concept, presenting a kind of mockumentary alternate history of Japan that focuses on various grifters who exploit these noodle bars. Bizarre concept, where the hell did that come from? It actually began in one of Oshii’s episodes of Urusei Yatsura, whose characters were adopted into the radio drama that preceded The Red Spectacles.

Why on Animation Night? Well, the technique used is a strange blend of live action and animation, described thus:

Tachiguishi-Retsuden is a documentary-style animation film created with an innovative technique named “Superlivemation”. Oshii first experimented this flat 3D technique in his 2001 live-action feature Avalon as a visual effect for explosions in Ash’s game, then he developed it, the following years, in both the MiniPato short films and PlayStation Portable game. Characters have a tiny body and an oversized head which makes them look funny. They are animated like paper dolls (ペープサート人形, papsart ningyou) and are evolving in a pictures based environment in the likes of the JibJab Brothers’ (Gregg and Evan Spiridellis) musical comedy cartoons, e.g. 2・0・5 Year In Review, although Mamoru Oshii stated his own work was a “serious comedy”. The Superlivemation consists of digitally processing then animating, paper puppet theater-style characters and locations based on real photographs. In Tachiguishi-Retsuden more than 30,000 photographs were processed 20 times, to produce the final composite to be animated. The director describes his new animation film as set between “a simple animation with extremely intense information” and “a live-action movie with extremely limited information”.

Avalon (TT#39) used the ‘superlivemation’ technique (which could be considered something like a variant on ‘pixilation’) for deaths in its videogame world; upon dying, a character would be replaced with a 2D composite before suffering a disintegrating effect. An entire movie shot with this technique sounds absolutely deranged, hopefully in a good way. I honestly have no idea how this one will play out; there may be a reason it’s almost unknown. But if Animation Night has one absolutely necessary element, it’s plumbing the archives for something fucked up and weird, so I’ll tell you what I make of it.

And that’s enough writing, let’s get going. With three films to get through, I’m gonna go live around now - I know it’s a lot earlier than it has been lately! I hope you feel like joining me; we’ll be watching StrayDog, Jin-Roh and then Tachiguishi-Retsuden in that order.

Hop in over at twitch.tv/canmom, mobies start in about 30 minutes (20:00 UK time)!

Final comments

So. About the Nazi thing.

If we start with the manga, Kerberos is a essentially similar concept to Ghost in the Shell (which is ofc in Japanese 攻殻機動隊 Kōkaku Kidōtai, “Mobile Armored Riot Police”) or Patlabor. It’s about a heavily armed, ethically dubious near-future paramilitary police force, the sort of people you’d find in such an organisation, and the political context that created it. Compared to GitS, its characters are much less vividly defined, but like GitS, it largely reacts to the world through the lens of Kerberos, and to a certain extent their rivals Public Security. Plotlines in Kerberos concern the individual lives of Kerberos soldiers, or the machinations of their leaders trying to expand the organisation and squabbling over territory with the normal police. It’s full of dog metaphors

Incidentally, if you’ve seen Jin-Roh, you’ve seen a better version of the first three storylines in the manga. The fourth one concerns radicals hijacking a plane, drawing on the actions of radical groups in the 70s. The leader of the the radicals takes more of a centre stage, although his motivations are kinda opaque at the end of the day; he seems like a prototype of the villain Yukihito Tsuge in Patlabor 2, at least in terms of affect, but he dies before his hijacking can get very far.

All of that on the face of it sounds reasonably interesting! The art of the manga is very nice in an Otomo-inspired sort of way, and while none of the characters are especially sympathetic, it’s a convincing window into an interesting historical pastiche.

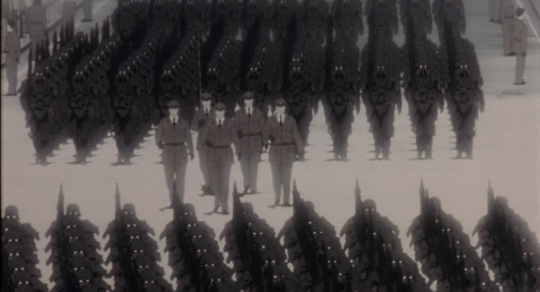

But the first thing you’d ever notice about Kerberos is that they dress like this:

…big scary Nazis with glowing red eyes. That’s the iconic image of the series, and just about every work makes sure to have some scenes of a guy dressed like that machine gunning some poor unarmored sods, to greater or lesser dramatic effect depending on whether or not you’re Hiroyuki Okiura.

So my biggest question going into Kerberos is like, why do they dress up like weird Nazi space marine cosplayers?

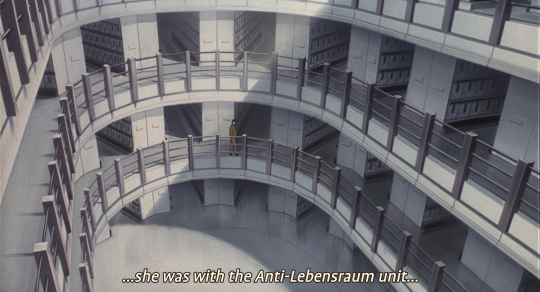

Diegetically, it’s because Japan lost WWII to the Nazis, who used a nuke. Most Kerberos media that I’ve encountered doesn’t especially seem to bother spelling that out, but Jin-Roh - easily the most artistically accomplished of any Kerberos media, sorry Oshii - goes far enough to illustrate it with historical-photo styled still images of Nazi soldiers marching up the streets of Japan:

In Jin-Roh, at least, Kerberos are clearly continuous with this occupation, with an almost identical shot of Kerberos soldiers marching shortly after:

How did Japan end up in a war with Germany, a country that notably does not border the Pacific, and how the hell did they end up losing so badly as to be occupied when Germany lost the war hard even with Japan’s help in reality? (Who indeed fought the war besides Japan and Germany?) But none of the Kerberos media I’ve read have tried to address this wider geopolitical situation; the role of replacing the Americans with the Nazis seems to be to just slap a lot of WWII-era German aesthetics in a rather superficial way: replace an airline with Lufthansa here, or have the slogans of the protestors mention Lebensraum or Weimar there.

‘Nothing would have been much different if the Nazis occupied Japan instead of the Americans’ is a statement that would have a lot to unpack (an anti-American statement? discomfort over being allied with the Nazis?), but I’m not sure it’s really what Kerberos is going for. If you look at otaku-oriented media from this period, you do notice a current of Nazi military equipment obsession (which hasn’t exactly gone away, indeed acquiring increasingly esoteric iterations) coming from the ‘military otaku’ side of the subculture.

For example, in Gainax’s FLCL, there’s an episode where Naota’s father Kamon is dressed in a Nazi uniform for a paintball episode (the same one which has parodies of Western animation like South Park), complete with swastika:

Likewise, Oshii’s adaptation of Urusei Yatsura also has a few recurring bits with Nazi imagery, generally played for jokes. For example, in the second movie Beautiful Dreamer characters dress up a café with a WWII theme with a bunch of Nazi symbols, which is discussed well by Hazel in her video on Vladlove (around 11:40 if the timecode doesn’t work)…

So there’s definitely a sense that in the subculture at this time, Nazi imagery doesn’t have the ‘definitely an edgelord, almost certainly an actual fascist’ connotation that it does over here. In Western media meanwhile, Nazis are generally used as the ultimate villains over whom we were victorious, suitable for when you portray some morally uncomplicated violence. So putting in these scary Nazi suits as your main characters feels like a really dramatic statement to me, but it may not have been for Oshii.

Nevertheless, let’s see where we go with it. My general approach to the Kerberos films has been to assume that Kerberos members are by default unsympathetic, it’s drilling into the fucked up depths of fash ideology, and Kerberos certainly admits that reading. A lot of the Kerberos manga concerns the organisation’s overly violent methods and eagerness to accumulate arms causing escalations and needless deaths left right and centre.

Jin-Roh especially shows Kerberos’s conspiratorial ‘Wolf Brigade’ carrying out a ruthless purge of their enemies to preserve their organisation, and then performing a completely fucked loyalty test by demanding that Fuse murder his girlfriend to prove his dedication to being a ‘wolf’. In contrast to the stylised theatric approach of Oshii’s violence, Jin-Roh’s scenes of bodies being cut down by machine guns are about as sickening and hyperreal as animation can make them - they are honestly far nastier than they would be in live action.

In Jin-Roh, the Metropolitan Police come off every bit as fanatical as they describe their enemies. The revolutionaries aren’t necessarily cast in a particularly positive light, with Kei as the main member of the Sect to get extensive screen time - and she finds herself thoroughly disillusioned with being a bomb courier as she gets drawn into the machinations of Kerberos and Public Security. But, even with the playing around the ‘who is the wolf’ concept, by the end we see Okiura’s take on Oshii’s endless dog metaphors is that committing to Kerberos is to decide to assume the role of the rapacious wolf of Red Riding Hood, who would shoot anyone to preserve the unit.

But what about Oshii’s manga? I talked about how Oshii was of the Anpo generation, and certainly the Anpo demonstrations - and the various desperate terrorist actions of the New Left that came after - sit barely under the surface. However, the point of view it’s interested in seems to be much more the lower ranking members of Kerberos. Like dogs - good god is this man obsessed with dogs lmao - the Kerberos guys are blindly loyal, have little other place in society, and are unceremoniously disposed of every so often. The main characters of the films feature here and there - notably Bunmei is the one scheming against Kerberos here, recognisably modeled after his depiction in The Red Spectacles, and Midori gets to stop the plane hijacking - but it’s as likely to focus on a low-ranking soldier (the first Inui, model for Fuse) or a helicopter pilot. There is not, by and large, a lot of internal conflict for any of the characters.

Tachiguishi Retsuden, although it seems a different alternate history again, gives another piece of the puzzle. (Unfortunately the only subtitles I can find for this movie are badly translated from the Chinese subs, which makes it a little hard to follow.) The stand-up noodle bars are associated not just with crime but with stray dogs, who were poisoned in large numbers as a health control measure; this image is also shown in the Urusei Yatsura episode that invented the ‘tachiguishi’ freeloader concept, where we see a dog and a cat fighting outside. Oshii clearly sees something tragic in the extermination of these dogs who had no place in the more modern society, and seems to find this a suitable metaphor for his fascist paramilitary.

To me, the idea that the Kerberos were heroic in suppressing the crime and protests seemed like an obvious propagandistic fantasy, and given the choice I’m obviously gonna sympathise more with the leftist rebels rather than the Nazi-backed state in this conflict, even if the situation has decayed as civil wars do into a point where both sides are more concerned with self-preservation and ruling their turf than winning. Painting the state in Nazi colours then seems like a way of saying, don’t take this guys very sympathetically, and it’s definitely a convincing depiction of a bureaucratic state mired in infighting (no doubt because it’s drawing heavily from history).

But… I’m not entirely sure this is the angle Oshii is taking on it.

In StrayDog, lost puppy Inui searches Taiwan for daddy Kōichi to tell him what to do, with the help of a girl Tang Mie who kind of adopts these two exiles as they do their homoerotic bonding thing. They spend a long time wandering around Taiwan to slow music (it’s a very Oshii film), having muted conversations about Inui’s need to find a master to tell him what to do. Once the pair find Kōichi, although Inui is angry with Kōichi for abandoning Kerberos, they settle down and seem to be kind of happy just being some kind of lobster-fishing polycule. Inui here can’t be the same Inui as in the manga (since that Inui died), but he’s basically the same concept, a boy who is helpless without someone telling him what to do [there’s not exactly a consistent Kerberos continuity so much as variations on the same ideas].

Public Security are on the trail though, and Inui - loyal to Kōichi despite the fact that Kōichi is plainly not worth any sort of loyalty - overpowers him in order to carry out a power-armoured suicide by cop and give Kōichi a chance to escape (which we know that he uses to go to Japan and promptly get shot). If the action scenes in The Red Spectacles were weird disconnected montages that felt extremely theatrical, the action scene here, which sees Inui advancing through a building cutting down identically trenchcoated and facepainted men who run blindly towards him, feels mostly like a video game. In the end, Inui wins the battle but dies from it.

(Which means on the one hand, highly stylised and abstracted live action violence, and on the other, hyperrealistic animated violence with plausible military tactics and genuinely horrible depictions of gun death. Going in opposite directions from different starting points… I’d say they end up in a similar place, but tbh Jin-Roh, as in most things, is way more impactful.)

Anyway, StrayDog seems to have more of an “isn’t this sad” sort of flavour. The dog metaphor for Oshii in the manga is stated most explicitly in a scene shared with Jin-Roh, where Bunmei discusses disposing of the ‘Special Brigade’ in order to integrate Kerberos with the regular police. The dialogue in both versions is a speech full of dog metaphors, but in the manga, the scene is further introduced with a dead Kerberos member and a stray dog passing by. This metaphor then becomes central to StrayDog.

The manga’s Inui, like Fuse in Jin-Roh, hesitates before shooting and almost dies, but here the person he hesitates to shoot is not a bomb courier who’s prepared to take them both down, but a civilian who is trying to help one of the revolutionaries, who levels a gun at Inui. Inui’s story here is about failure to integrate into the Kerberos unit, who aren’t willing to accept this particular ‘stray dog’ despite there being no other place for him. Inui tries to prove himself with dramatic and reckless violence, gets rejected for refusing orders, and then on his way home, gets killed in a reprise of the first situation - oh this poor boy it’s so sad.

In Jin-Roh by contrast, Fuse’s hesitance to shoot is the first move in a whole character arc - at first it seems like his remaining humanity which he eventually abandons, but we are left with some ambiguity whether his original hesitance was genuine, and happened to pay off in the Wolf Brigade’s favour, or part of a very complicated ploy. (Despite being the central character, and even seeing his dream at one point, we’re given a lot of room to interpret Fuse, and the ‘why didn’t you shoot’ question is pointedly never answered.)

Anyway, so, my conclusion about all the Nazi imagery in Kerberos is… honestly I think Oshii just thought it’s cool? As we see in VladLove, he loves to just namedrop historical trivia. I’m not sure he even considers it as fraught as I do. Which isn’t fun but I feel like any other reading is unparsimonious at this point.

What is surprising is that Okiura managed to take what Oshii was putting down and make something genuinely compelling. Jin-Roh a real proof of the power of his realist style and ability to suggest character with subtle acting. Its realist animation becomes hyperreal, the abstraction of cel shading underlining how much is ‘right’ in how the drawing moves, and it works for what’s primarily a spy movie.

At the same time… Okiura did a way better job than Oshii ever did of making those scary Nazi suits seem powerful. Kerberos here are kind of the idealised supercop Judge Dredd types - I was reminded of the Dredd movie from a few years ago where Dredd unstoppably advances through a building, killing everyone in his way. Though maybe Robocop would be a more contemporary comparison.

It works for the movie, in that Fuse’s choice to side with Kerberos and use the armour to massacre the Public Safety agents moving to apprehend him is properly sickening. It becomes kind of like a horror movie at this point, with desperate attempts to stop him with grenades bouncing off the armour.

So I guess we’ve gotten back to the old question of the different ways of portraying violence in film, what a fascist film looks like etc. I don’t want to relitigate that one, although I think Okiura’s angle is appropriate - even if it is fetishistic? One Youtube commenter on the video essay I linked back on AniNight wrote:

Jin Roh is a movie about semi-realistic bullets physics. The creators be like: Guy 1: ‘Hey, you know what’s cool? Seeing dolls gets rag-dolled by flying bullets.’

and he’s kinda right lol, that is sorta what the movie is about. But it remains a very effective image, much like the gunfights and realistic educations in Dahufa.

All in all, I guess the result of this deep dive is basically the existing consensus: The Red Spectacles is worth digging up as a deeply weird surreal film; I wouldn’t bother with StrayDog, the manga’s OK but Jin-Roh is imo the only one that manages to justify what it’s trading in here.

And as far as all these Nazi images goes, the aspect of the Nazis we’re focusing on in any of these films is much more ‘fearsome invading and occupying power’ than ‘perpetrators of the Holocaust’. If Nazi ideology has influenced the reconstructed Japanese state in the world of Kerberos, the series never bothers to illustrate how. Despite everything… it really doesn’t seem to actually be about the Nazis on a level beyond the superficial. The conflict in Jin-Roh/the manga is basically a heightened version of Anpo, or like… any 20th-century anticolonial movement really. In the first two movies… idk, throwing darts at a board, the Meiji restoration doing away with the samurai lol?

Meanwhile Tachiguishi-Retsuden is kind of… ah, I know some of ya had fun with it, but honestly I found it dragged really badly. The janked out subs were a large part of that and I think a decent fansub could do it a lot of good, but I kind of felt like most of the gags went on too long to really work, even with the ‘spot the well known illustrator/anime director’ game it’s playing with the casting. Though maybe being tired after a long evening of films underlies that reaction, I need to learn my lesson about three-movie film nights. The animation style was interesting as an experiment at least.

And that’s quite enough of that, I think I’m satisfied. Though at some point as far as ‘fash aesthetics in anime’ go, I still haven’t gotten around to ripping Youjo Senki a new one. Expect that… sometime. It’s an exhausting anime to think about though so who knows when.

Comments