originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/658688...

Hello friends! It is a multiple of 5 tonight, which means, according to my arbitrary definitely-always-followed schema, tonight is a theme night focused on some kinda animation technique… and tonight, that means the rotoscope!

So what is a rotoscope? In the modern day, the term refers generally to drawing over live action footage with animation - very easy to do in the digital era!

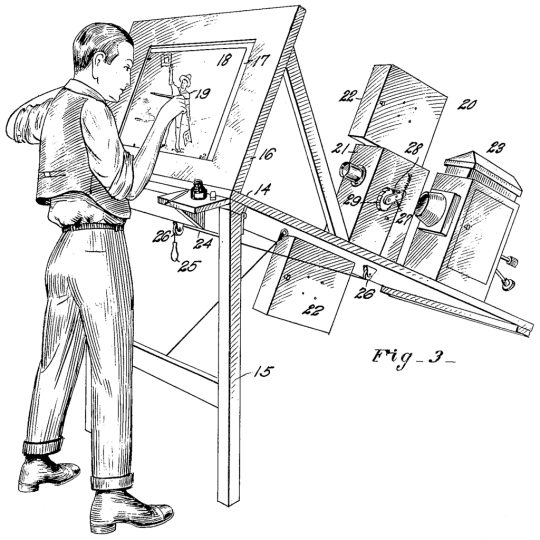

But in its original form, the rotoscope was actually a contraption built by Max Fleischer to enable him and his animators to accomplish that in the era of physical film…

…by projecting the film behind the drawing surface to shine through the paper. With this technique, the Fleischer brothers were able to create some of their most world-known films, starting with shorts like Out of the Inkwell and eventually reaching the Cab Calloway performances we talked about back on Animation Night 21.

Before long, the contraption would find its way into the hands of Disney. In The Illusion of Life, the book that declared the ‘12 principles of animation’, Thomas and Johnson discuss starting on page 318 how it was used in the earlier days of the studio: while trying to figure out how best to express the character of Dopey the dwarf in Snow White, someone suggested that they should look at the performance of burlesque comedian Eddie Collins. The animators piled into the theatre, then invited him to the studio to perform interpretations of the character, which they filmed and used to inform their animation.

This worked so well that they started inviting “entertainers from vaudeville, men who had done voices for the other dwarfs” as well as filming random members of Disney staff. They write:

As resource material, it gave an overall idea of a character, with gestures and altitudes, an idea that could be caricatured. As a model for the figure in movement, it could be studied frame by frame to reveal the intricacies of a living form’s actions.

At first, these frame by frame studies were done using a Fleischer-style rear-projection rotoscope; before long they developed a system of printing out the films onto ‘photography paper the same size as our drawing paper’ called photostats. There’s a very cool passage where they get excited at what could be discovered in there…

We were amazed at what we saw. The human form in movement displayed far more overall activity than anyone had supposed. It was not just the chest working against hips, or the backbone bending around, it was the very bulk of the body pulling in, pushing out. stretching, protruding. Here were living examples of the “squash and stretch” principles that only had been theories before. And here was the “follow through” and the “overlapping action,’’ the changing shapes, the tensions and the counter tensions, the weight shown in the “timing,” and the “exaggeration”—unbelievable exaggeration. We thought we had been drawing broad action, but here were examples surpassing anything we bad done. Our eyes simply are not quick enough to detect the whole gamut of movement in the human figure.

So at this stage, Disney primarily used these studies as reference to be interpreted and developed by the animator, rather than directly copied. And they also discovered the peril of rotoscoping, a certain uncanny lifelessness:

But whenever we stayed too close to the photostats, or directly copied even a tiny piece of human action, the results looked very strange The moves appeared real enough, but the figure lost the illusion of life. There was a certain authority in the movement and a presence that came out of the whole action, but it was impossible to become emotionally involved with this eerie, shadowy creature who was never a real inhabitant of our fantasy world.

(…)

The camera certainly records what is there, but it records everything

that is there, with an impartial lack of emphasis. On the other hand, an artist shows what he sees is there, especially that which might not be perceived by others.

Disney made increasing use of live reference over time, since it proved a useful way to plan out and judge shots in the early stages. This had its pitfalls…

Unless a director is exceptionally wise, or an animator himself, he should ask the man* who ultimately will animate the scenes to help plan the business on the stage. Almost always when someone else shoots film for an animator the camera is too far back, or too close, or the action is staged at the wrong angle to reveal what is happening, or it is lighted so that what you want to see is in shadow. Occasionally the footage will show only continuity of an actor moving from one place to another, or just waiting, or getting into position to do something interesting later on. The action must be staged with enough definition and emphasis to be extremely clear, but neither overacted nor so subtle that it fails to communicate.

(*this would have been a man, because old Walt banned women from being animators - we would have been restricted to the ink and paint department up until Reidun “Rae” Medby was first permitted to work as an assistant animator in 1944, in the wake of the animators’ strike and a lot of animators going off to war after the Pearl Harbour bombing.)

By the time of Cinderella, a cash-strapped Walt decided he needed another feature film to pay for the not-yet-profitable Pinnochio, Fantasia and Bambi. (Strange to imagine Disney ever struggling for money, but it wasn’t quite the monster it became back then.) To save as much effort for the animators as possible, he shot basically the entire film in live action, which was closely followed by the animators:

A new, less expensive way to make the projected Cinderella as a full-fledged animated feature had to be found. Reasoning that animation was the most costly part of the business, Walt felt that everything possible should be done to save the animator’s lime, to help him make that first test “OK for cleanup” without correction. He turned to live action to solve his problem.

All of Cinderella was shot very carefully with live actors, testing the cutting, the continuity, the staging, the characterizations, and the play between the characters, Only the animals were left as drawings, and story reels were made of those skelehes to find the balance with the rest of the picture. Economically, we could not experiment; we had to know, and it had to be good. When all of the live film was spliced together, this was undeniably a strong base for proving the workability of the scenes before they were animated, but the inventiveness and special touches in the acting which had made our animation so popular were lacking. The film had a distinctly live action feel, but it was so beautifully structured and played so well that no one could argue with what had to be done. As animators we felt restricted, even though we had done most of the filming ourselves, but the picture had to he made for a price, and this was, undeniably; a way of doing it.

The extent of rotoscoping in Disney films has always varied; after Cinderella they continued to use live footage for films like Peter Pan, but would interpret it more creatively. A lot of this close study of film was applied to animals. For The Lion King, they actually brought real lions into the studio, so you get these very cute videos of a baby lion being led between a row of drawing desks and getting petted by the animators (skip to 1:35…)

So that’s Disney. They had a particular way of using rotoscopy. Later they’d use live footage in different ways - with 101 Dalmations, they actually drew lines on a toy car and filmed it, then xeroxed the film, to create what appeared to be a line drawing.

In the 70s, as a few people started to escape the Disney orbit and their somewhat stifling house style, animators like Ralph Bakshi also got the rotoscopy bug, in part as a way to create animation with limited costs. We saw the results a couple of weeks ago in Wizards and Lord of the Rings (as well as American Pop and Fire and Ice which we haven’t seen yet). The former of these did some pretty wild experimental techniques, such as xeroxing war scenes from existing movies - resulting in a delirious, dreamlike battle sequence. For LotR, almost all shots were either rotoscoped or solarised video footage; presumably a fully live-action cut of the film could be made from all the test footage.

The results of Bakshi’s experiment were… mixed. At its best, the rotoscopy in LotR gives its characters a great degree of weight and solidity appropriate to a more ‘serious’ fantasy movie. The decision to solarise video footage for the battle scenes, or the really long chase sequence in the middle of the movie, is a fun and vivid experiment… but it’s no surprise it didn’t catch on.

Don Bluth (Animation Night 23 - animals, 31 - hanukkah) also used rotoscopy in his films The Secret of NIMH and An American Tail, as well as the same xerox trick as 101 Dalmations for semi-stylising physical objects. This ends up much more successful on the whole: while the physical objects stood out, they work as a particular style, while none of the character animation seemed ‘obviously rotoscoped’. On the donghua side (Animation Night 27), rotoscopy was used in Princess Iron Fan. And through the latter half of the 20th century, there were many other films using the technique which I’ve yet to cover, which you can read about over on WP.

20th-century rotoscoping tended, with some exceptions like Yellow Submarine, to aim for something approximating traditional Disney-style animation with flat colours and caricatured designs. In anime, rotoscoping does not seem to have been especially common, likely because the generally limited drawing counts really force a different approach to timing than strict realism.

All of this changed as we approached the 2000s. In the West, MIT researcher and frequent Liquid Television animator Bob Sabiston developed a program called Rotoshop that eased the work of rotoscoping by interpolating between drawings. (We might compare this with EBSynth, which requires only a few frames to stylise a whole video sequence - Rotoshop on the other hand takes a much more granular artist-controlled approach, but it is consequently more time consuming).

Sabiston’s software caught the attention of live-action director Richard Linklater, who used it in two films, Waking Life (2001) and an adaptation of Philip K Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly (2006). These films proved pretty popular in arthouse circles, and the clips show a striking effect, with the shading of the face simplified into shifting vector shapes that’s very consciously uncanny.

Over in Japan, in 2013 Hiroshi Nagahama and studio Zexcs experimented with adapting the manga The Flowers of Evil into a fully rotoscoped anime TV series. The result is an anime that looks very unlike typical anime: characters constantly moving and breathing and rotating subtly in 3D space. This seems to have been extremely polarising: some critics lavished praise on its cinematography and unusual style, but it also caught a lot of flack for cutting corners.

A second anime attempt at rotoscoping arrived a couple years later in Shunji Iwai’s film The Case of Hana and Alice, a prequel to his 2004 live-action film Hana and Alice. This one seems to have landed a lot better, with rotoscoping allowing them to portray what would otherwise be extremely difficult scenes like this roomful of dancers:

It’s very interesting looking at these clips: the style leads me to read them as traditional animation, and then is immediately struck by the perfect perspective and weighty movement of cloth and bodies - I get that “how could anyone have…” feeling. That is perhaps the great power of rotoscoping: it allows us to look at things that would otherwise be everyday and see the fascinating complexity of motion going on at every moment…

One thing that strikes me about both of these films is that both use a kagenashi (flat-shaded) style, much like the films of Mamoru Hosoda. The same is true of Bakshi’s LotR. This makes the characters fit oddly into the scenes: exceptionally 3D the subtle changes of contour, but shaded perfectly flat. It’s a nice effect but I wonder why so many rotoscoped films ended up here? Perhaps it is much more difficult to draw out shadow shapes on a frame by frame basis than the obvious contours of a character…

Rotoscoping has also been used occasionally in other animated films, such as the beautiful dance scene in Your Name by the young Naoko Kawahara. There are also some rather amusing cases, like the idol anime Love Live quietly rotoscoping multiple shots from the American live-action musical show Glee.

The next major film experiment in rotoscoping came in 2017, a biopic of Vincent van Goph directed by Polish filmmakers Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman. Kobiela is a painter herself, and got the seemingly mad idea of making a film that is entirely Van Goph-style oil paintings shot on 2s, making for 65,000 drawings over a 90 minute film. They took this idea to Kickstarter and the usual European art funds, and, wildly, actually made it work. The result is characters that move with all the subtlety of real film, but with the beautiful textures and abstraction of impressionism.

The production involved a multi-step process: CG animation and live footage would be composited together to get a close approximation of the intended frame, and then it would be fully repainted by a team of 80 oil painters. The various shots of the film are composed after van Goph paintings, but many edited to change the time of day or adjust the framing from one of Goph’s vertical compositions.

Anyway, even for a really skilled oil painter with a good reference, I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to keep the subtleties of each painting consistent frame to frame. It landed at Annecy to enormous acclaim. Judging by the short films at Annecy this year, this kind of paint-rotoscoping seems to have taken off since then, to somewhat varied effect. While For their part, the makers of Loving Vincent are currently creating another oil paint rotoscoped film titled The Peasants…

This technique has some similarities to the paint-on-glass method made famous by the Russian animator Aleksandr Petrov, but while paint-on-glass is destructive, overwriting each frame with the next creating a situation where frames blend into one another, I believe the method of Loving Vincent is to create an entirely original oil painting for every frame. (I presume they have some digital trick to help them composite it onto the backgrounds, which seem to remain static).

So, what’s the plan tonight? We’re going to check out The Case of Hana and Alice and Loving Vincent, one or two episodes of The Flowers of Evil, and a few of the shorts by Bob Sabiston. That certainly doesn’t cover the whole story with rotoscoped films, but I think it should give us a nice little cross-section!

Animation Night 65 will begin at 7pm UK time (about three and a half hours) at twitch.tv/canmom. Hope to see you there!

Comments