originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/671411...

Hello friends! If you are of the inclination to celebrate some sort of “WINTER HOLIDAY” i do hope you are having a pleasant time. And conversely you are currently stuck visiting a family you’d rather not see I hope you get to leave soon.

Tonight is a night ending in 5, which by recent tradition means I should gather some films unified by technique. In fact, this instance is something of a coming together of the last two, rotoscopy and early 3DCG… so, grab your tasty plasmas and let’s look in to the subject of performance capture!

(Pedants will insist on a difference between ‘motion capture’ (captures only broad body movements) and ‘performance capture’ (also captures facial expressions) but honestly who cares. i’m going to be using the terms interchangeably.)

Nowadays, the line between a 3DCG animated film and a high budget ‘live action’ film is more of a continuum. On one end you have a movie like Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, (not-Toku tuesday 21) which features live actors in mostly real sets with some additional CGI work to fill in missing parts of the sets in some shots. In the middle you might have something like Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, featuring mostly real actors in practical sets but with extensive matte painting composites and full-CG shots, and certain characters instead presented through mocap. At the more extreme end, you would have something like the Wachowskis’ Speed Racer or the Star Wars prequels which composite their actors into 3D renders in almost every shot.

And then, we have movies presented entirely through motion/performance capture, which seems to be the line where it becomes considered ‘animated film’.

So let’s talk about mocap! And heck, check out this gif, I don’t know the context but it’s funny how the computer insists on aligning the feet with the floor:

So let’s briefly describe the technique. 3D computer animation almost always uses a ‘rig’ to control the animated character: a hierarchical structure of ‘bones’ which are, internally, each a transformation matrix in 3D space. So for example the finger bone will have some translation, rotation and scale, and it may depend on the hand bone, which depends on the forearm bone, which depends on the upper arm bone, which depends on the shoulder bone, which depends on the upper spine bone, which depends on the ‘root’ bone of the rig.

To determine the full transformation of the finger bone, you compose all of these transformations: root, spine, shoulder, upper arm, forearm, hand and finger in order. This gives you a position and orientation in 3D space.

When we animate a 3D character, we move and rotate the bones in 3D space. Rigs can be very complex, with switching between forward and ‘inverse kinematics’ systems (you can place a hand and the other arm bones will be placed in the appropriate positions), facial expression blendshapes, and all sorts of derived components such as simulated muscles which stretch appropriately.

This gif I pulled out of the gif searcher demonstrates the principles. The upper torso bone is rotated, and all the arm bones rotate with it.

The model is ‘skinned’ by assigning each vertex a certain weight for every bone, and then using these weights we can displace a vertex from its original position to a new one that averages the transformations of various bones. Creating ‘good deformation’ is its own complicated subject: you want the model’s volume to stay consistent, and you don’t want noticeable stretching, or weird bumps and self-intersections created by bad topology. (The above gif shows a number of deformation problems which cause the model to fail to match the rig.) For more subtle rigs, tools exist to simulate muscles, support softbody simulation for fat deposits, and simulate cloth draping over the model.

The kind of animation you can do with a 3D model is heavily limited by the quality of the rig. Nowadays, there are many very sophisticated tools to automate the process of rigging, and well-designed rigs available for download, but this body of knowledge is something we’ve gradually built over the last few decades.

So when did mocap begin? We might be inclined to imagine it would be around the start of the 2000s, as CG character animation started to become a presence in movies; it would be easy to speculate (and was my initial supposition) that artists started to recognise that they could use video of real actors to drive these rigs instead of keyframe animation. But motion capture is actually considerably older than this…

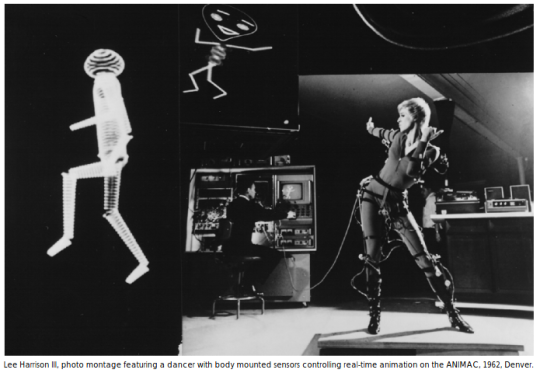

The earliest instance seems to lie with Lee Harrison III of the Computer Image Corporation in Denver. He’s best known for the Scanimate system used for analogue video motion graphics in the 60s and 70s (see documentary here). But around the same time, Harrison created a system called ANIMAC, which created computer animations using a physical rig.

There is unfortunately very limited information available on the internet that I’ve been able to find, but there is an article on it here. Rather than the video tracking approach used today, ANIMAC used a special harness of potentiometers which measured the angles of various joints; these angles could be used to drive a model - at first, just a stick figure. The animation system used a similar bone rig to what we discussed above, but more often with rigid models than soft, interpolated deformation.

And using it was incredibly #aesthetic:

The motion capture component of ANIMAC/Scanimate was only rarely used; the novelty was not enough to get over the lack of immediately appealing designs. One example that used it was the comedy variety show Turn-On (1969) discussed in this VICE article which was infamously cancelled almost immediately. Before too long the ANIMAC was destroyed to make space, and Scanimate was used largely for motion graphics.

It would take until 2000 for a full mocap movie in the form of Sinbad: Beyond the Veil of Mists, with the mocap footage shot in Los Angeles (ft. some surprisingly high profile actors) then processed into animation at the Indian studio Pentamedia Graphics. You can watch Sinbad in full on Youtube, in a rather bizarre upload where the left channel is in English and the right channel is in Hindi, or a full Hindi version below. It had some surprisingly big names on the English cast, but made almost nothing, perhaps because the visual style is… offputting. Have a click through…

It looks like a videogame cutscene… and what of games, anyway? Apparently the first game to make extensive use of true motion capture (as opposed to video sprites as in the 2D Prince of Persia games) was Virtua Fighter 2 (1994), a 3D fighting game, although the studio previously tested the technology for the pit crew in Virtua Racer. You can see the evolution of their techniques in this video (click through to the description for details):

It seems to have spread first in the Japanese industry, and Square first picked up the tech for Final Fantasy VIII (1999), using it to drive pre-rendered CGI cutscenes. We’ll come back to them very shortly.

And now… we hit the Remington Scott Productions era.

The early 2000s were apparently deemed the time for mocap to debut. The year before, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace had demonstrated to the world that it was possible to put a minstrel character in a modern movie if you made him a mocap alien. This character, Jar-Jar Binks, was very poorly received, but the studios did not give up; the next major attempt was Andy Serkis’s performance as a tortured, dissociative Gollum in Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), which gathered extensive praise. The latter worked with a guy called Remington Scott, who had made his name on a certain Square project…

Over in Hawaii, Square had founded an animation studio called Square Pictures with the hope of creating photorealistic, mocap-driven CG animation. Their first project was a massively expensive animated film called Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. Although directed by series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi, the film had very little to do with the plot of any Final Fantasy game, or any of the recurring elements of the series; filmed in English, it took more of its cues from a general sci-fi milieu which we might see reflected in films like Sky Blue/Wonderful Days (Animation Night 20). The project, begun in 2008, demanded lot of time from animators to clean up the mocap footage and a hefty custom render farm; Producer Chris Lee argued the expense as justified because this was a grand, pioneering passion project similar to Disney’s Snow White (Animation Night 84).

The mocap data acquisition was led by that guy we just mentioned Remington Scott, who still proudly reports on the quality of mocap data he was able to acquire. Scott appears to have gotten his start in the late 80s, inserting FMV characters into boxing games. then further in games in the 90s at Acclaim Entertainment’s dedicated motion capture studio. By the time of Spirits Within, he was running the whole project.

Unfortunately, Spirits Within did not land to nearly such success as Snow White. The promise of being “the first to simulate human emotions and movements through computer graphics” was generally speaking considered a failure; reception focused on the idea of the ‘uncanny valley’, and critics judged the plot to be dry and cliched. With such a high-profile failure on their hands, Square Pictures did not have long left to live; they did, however, last long enough to create a segment on the Animatrix (Animation Night 6), titled Final Flight of the Osiris, notably using the tech to blend the performances of three different actresses in one 3D character to take advantage of their respective strengths (acting, gymnastics, etc.). Scott left to work on Lord of the Rings and became a recurring figure in the VFX industry.

Despite this reception of their magnum opus, the animators and technologists were not deterred, and kept taking more money as they attempted to cross this so-called ‘uncanny valley’. More computing power was directed at ever more detailed models of human biology and the interaction of skin with light scattering, and by this point it is pretty much expected that a sufficiently high-budget scifi movie will feature mocap characters. Meanwhile, as computer games started to converge on a realtime version of the Hollywood realist paradigm, people started to get more comfortable looking at hyperreal CGI faces, and the ‘valley’ became shallower.

If you read more recent copy on Scott’s site, it starts to sound like something from a dystopian novel. For example, describing his work for Chinese film L.O.R.D.: Legend of Ravaging Dynasties (2016) (which admittedly looks fascinating, and I hope I can find a source at some point), Scott declares:

GEMINI TECHNOLOGY, developed for production in high resolution IMAX 3D feature films, re-creates the exact likeness of the actor. Skin is de-aged and beautified, essentially turning back the clock to a more youthful age, yet retaining the essential details.

He also reports on animating the dead, e.g. recreating David Bowie on stage. Or maybe you want the closest thing yet to a nationalist VR snuff film, with ‘Seal Team Six Virtual Reality’? No doubt his next act will be the Torment Nexus VR (with blockchain technology!)

Not all motion capture goes for all out hyperrealism, though. Robert Zemeckis, known for Back to the Future and in animation, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Animation Night 40), got the mocap bug hard in the 2000s, starting with The Polar Express (2004). In this case the mocap was motivated by affordably recreating the visual style of the children’s book he was adapting, but the experience motivated him to make a whole string of other mocap movies: Monster House (2006), Beowulf (2007), A Christmas Carol (2009), and Welcome to Marwen (2018).

By this point we’re a few years on from LotR and Final Fantasy, and the tech is a little more developed. It was nevertheless still an experiment. At one point Zemeckis wanted lead actor Tom Hanks to play every character in the film, but this was too exhausting for Hanks, and others were brought on. Most of the animation seems to have been done at Zemeckis’s studio ImageMovers, involving Doug Chiang who later became head of LucasFilm as a ‘production designer’.

The film is framed around a theme adult nostalgia for being a child who could easily and uncritically accept narratives like ‘Santa Claus’ (c.f. America Observations 3 where I found myself compelled to note the origins of christmas symbols). It mixes the ‘Santa Claus’ story with a notion of the supposed infrastructure behind it; a child accepts an invitation to board a special train to Santa’s workshop in the north pole, goes through a variety of symbolic experiences with the train’s conductor, and then arrives in the elf workshop where the children are placed in competition to receive the ‘first gift’. The best thing about it is apparently, if you ask someone like Ebert who seems to just love this kind of mocap movie (all of the articles mention his high praise for them), is the somewhat creepy atmosphere.

The film landed to mixed reception, once again drawing comments of stiff acting and ‘uncanny valley’ creepiness - not to mention complaint that Zemeckis would serve such a ‘schmaltzy’ christmas movie. However, this did not prove as fatal to ImageMovers as Spirits Within did to Square Pictures. Their subsequent films take on a variety of tones - the only one I’ve seen is their adaptation of the famous Old English epic poem Beowulf, which is… strained lol and features the bizarre decision to make Grendel’s mother super fuckable (by normie standards). At some point I want to be there with @baeddel watching it lmao

Our final one in this hopefully representative triangulation will come from the end of the first decade of the 2000s, when some of the blockbuster directors got interested in using this now somewhat more mature tech. James Cameron finally had the opportunity to create his hardish sci-fi white saviour passion project Avatar, and it was for a brief period the highest grossing film ever, yet managed to leave next to no impact on popular culture. At some point I guess I will get around to watching it but I’m not especially in a hurry. The animation for this film was performed at Weta Digital, same as LotR.

And not long after, Steven Spielberg decided to get in on the action with an unusual adaptation of Hergé’s famous adventure-story bande dessinée (c.f. AN 71: Moebius), The Adventures of Tintin, about a reporter who alongside his friend Captain Haddock finds himself having Adventures in various countries; in this case, it’s a loose adaptation of the Tintin story The Secret of the Unicorn in which the pair seek the treasure of a pirate who fought Haddock’s ancestor.

A full account of the history of the Tintin comics, gradually evolving from extremely racist origins like Tintin in the Congo (bc the French and Belgians have almost unparalleled nostalgia for their African colonies, Belgium particularly infamous for the brutality of King Leopold’s rule of the Congo) to become a - for their time!! - fairly well-researched series of travel comics, will have to wait for another occasion. Hergé used an iconic style in a tradition known as ligne claire, with flat shading and carefully minimal linework on characters amidst detailed backgrounds, and up to that point, the various animated adaptations of Tintin have used similar hand-drawn character designs.

Spielberg had other ideas. He decided on a tack of almost-realism; the costume design and overall proportions tend to reflect the comic, but the characters’ skin would have realistic shading and tone variations, and faces would move in realistic ways driven by mocap, with various action sequences following the dominant conventions of Hollywood stunt filming (e.g. highly mobile camera, use of slow motion, improbable physics coincidences).

At this point, the VFX industry had become so split into Taylorist production houses that it’s hard to work out who actually did any particular thing. So while we can read about where principal photography was performed, and even watch Weta’s upload of VFX breakdowns for the film, it really starts to feel like it lacks any personal touch in terms of animation. Everything, the camera especially, is in constant, almost overwhelming motion, without any stillness for contrast. Like Disney’s ‘full animation’, this ideal functions - whatever the intentions of its creators - as a display of expensive excess.

I’m not necessarily against this. It worked great in for example Speed Racer, a natural fit to the themes and tone of that film. But as a dominant paradigm it’s exhausting! And the popular discussion seems to prefer to obscure the ‘how’, so that the images seem to magically manifest from the power of the mighty new computers and genius of the tech industry, instead of letting us be familiar with the exact painstaking way that the various images and elements are composed together which is actually very interesting.

Tintin at least presents its spectacles with a kind of clarity; motion blur is still heavily present, but the scenes are brightly lit and at least somewhat colourful, and the camera does not try to obscure it subjects. It will be interesting to see the full film, but I recall most peoples’ reaction at the time being a kind of ‘huh.’ and ‘why do that?’ and I kind of expect I’ll feel the same…

So, we’re starting horrendously late, but the plan is three movies from across the first decade of the mocap era: Spirits Within to open it, Polar Express as another early foray, and then Tintin to show where it went after. Full-mocap movies never really seem to have caught on over live action compositing, but filmmakers keep probing at the technology, so who knows if all big budget movies will end up working like this at some point.

Anyway we’re going to start almost immediately now (1am UK time, 5pm US time); apologies to UK viewers, I definitely want to get Animation Night back to the original time before too long. As much as it brings shame on me, I am showing a christmas movie next to christmas, so please feel free to mock and deride as far as you feel appropriate. See you soon at https://twitch.tv/canmom!

of last night: Spirits Within is truly the epitome of 2000score, managing to perfectly elicit the feeling of a videogame cutscene compilation on youtube. sometimes that game is an fps on the xbox and sometimes it’s the longest journey. there’s a point where the black marine, woman marine and steve buscemi marine all die in quick succession.

it was interesting watching it back to back with Final Flight of the Osiris just how far their ability to render skin and cloth, not to mention skill at film direction, improved in the space of a couple of years. it would have been fascinating to see where square pictures would have gone; they live on in squeenix’s pre rendered promo video/movie tie-in department, but it would be cool to see those guys get to make a non tie in movie after that experience. I’m sure it would be ridiculous and stilted in all the ways spirits within was, but that’s quite endearing.

i went in to the polar express with my expectations on the floor. the opening part, when the train seems relatively menacing and various guises of tom hanks manifest to torment the children, including an elaborate dance about hot chocolate, had at least some fascination thanks to the various bizarre creative decisions to attempt to drag a very short children’s book out into a full length movie. once it gets to the north pole it just gets painfully tedious at best. had it been a horror movie, with a sense of reserve about using the usual horror movie markers, and just committed to the hints of elftown as some sort of lurid fascist enclave, it might have been something. idk. pretty much what i expected but it did scratch the historical interest angle i guess. i really do hate christmas movies.

tintin was sort of interesting as an illustration of how much all the rules about making technically ‘good’ art are irrelevant to making something effective. by this point all the kinks in the cg process had been ironed out. the characters, despite the bizarre stylisation, can act convincingly, they’re well lit (the lighting is carefully designed to draw focus and layer scenes.), etc. the setpieces are narratively clear and space out their jokes by the book. there are occasional filmmaking flexes like an intricate action sequence that spans one very long take (animation cut), or flashy effects driven transitions where scenes morph from one to another (a desert into an ocean, a character’s face and thumb into rocks on a ridge, a character’s glasses reflecting a scene into which the camera pulls back) which take care to remind you that spielberg is a big name movie director. the story faithfully ticks off the beats of a tintin comic: head injuries, bumbling thom(p)son antics, chloroform, seaplanes, open topped cars, franco-belgian colonial nostalgia, awkward orientalism (likely less so than hergé’s original but still very present in the story structure). the only deviation from tone is tintin having a brief crisis of confidence which haddock talks him out of with a motivational speech, which I’m sure you could find suggested in some kind of screenwriting manual.

and yet the overall effect of it is just… nothing. i do not think I’ll remember much of this movie in a week. despite the vast effort and expense, it evinced little more emotion than the same 'huh’ when i first heard about it.

something about the film industry produces these director guys with plentiful technical skills and enough name familiarity to get bums in seats, as well as a lot of 'auteur’ freedom, but they’ve run out of interesting things to say with their movies many years ago, and yet because of their reputation they get to do whatever they want pretty much unconstrained. so you get these lavish but weirdly empty, kind of mechanical productions: more elaborate than the movies that made their names but far less impactful. i feel like ridley scott is another example, or indeed the wachowskis (even before reports of the new matrix movie). it’s not just the west though - you could say much the same of hayao miyazaki. i don’t have much attachment to earlier spielberg honestly, but it definitely feels like whatever people liked about him, it doesn’t pertain anymore. who now talks of tintin? i don’t know what to take from that - you could say something about bourgeois art (as these guys get rich they get insulated from anything worth expressing in art), or the importance of constraints to creativity, but that’s all kind of pat. perhaps instead it’s something about the infrastructure of movies on this scale, the very strict design iteration process of vfx houses tending to purse their lips over any interesting individual contribution that takes any sort of risk, and pulling it back to the boring standards of the industry. whatever it is, it’s sad to see that 'spark’ of personal interest or passion die. I’m dreading when it catches yoko taro lol. perhaps it has already.

i definitely intend to schedule some more compelling stuff for next week to mark the end of the year. possibly some of the super depressing end of my own country’s animation - i have had my eye on Plague Dogs for a while, and it might make a 'fun’ companion to Pink Flloyd’s The Wall. anyway, we’ll see. seeing more American animation definitely underlines that concept in sakuga fandom about anime’s production process tending to give more room to individual key animators to leave a mark on the final product…

Comments