originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/146331...

sphere-sounds, who has now sadly deactivated their Tumblr, asked:

I just had an idea: a maglev mass driver for space launch that's similar to the "StarTram", but accelerating in a circular loop similar to the LHC. What I want to know: how big a loop would I need to hit 10 km/s speed while keeping rcf under 4g?

Centripetal acceleration of an object moving in a circle is given by $$a=\frac{v^2}{r}$$ where \(a\) is the acceleration, \(v\) is the linear speed of the object, and \(r\) is the radius of the circle.

Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF), for anyone like me who hadn’t heard this term, is simply the centripetal acceleration expressed as a multiple of \(g\) (the standard gravitational acceleration at Earth’s surface).

So quick rearrangement gives the minimum radius as $$r_\text{min}=\frac{v_\text{max}^2}{a_\text{max}}$$ which, plugging the appropriate numbers into wolfram alpha, comes out as about \(2500\unit{km}\), which is to say, about the radius of Mercury.

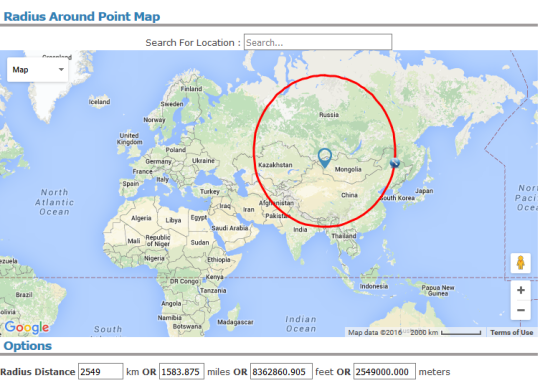

Plotted on a map using this tool, it looks like you could just about fit this loop inside Eurasia and still have it mostly on land (or with a bit of nudging, entirely inland):

Of course such a route requires the launch system to pass through a range of elevations from sea level to the Himalayas, and have high-performance electromagnets/charged rails/whatever along the entire \(16 000\unit{km}\) length. (For comparison, the LHC’s main beamline is about \(85\unit{km}\) long, and its radius is about \(12\unit{km}\)).

If the accelerator works on similar lines to the LHC, i.e. using a dipole electromagnetic to produce a constant magnetic field to accelerate a charged particle perpendicular to its motion, we can calculate how strong the magnetic field needs to be. the magnitude of the magnetic force on a moving particle in a perpendicular magnetic field is given by \(q v B\) where \(B\) is the magnetic field strength, \(q\) is the charge on the particle, and \(v\) is its speed. Equating this with the centripetal force needed, we get $$qB = \frac{ma}{v}=\frac{mv}{r}$$ so we can increase the acceleration by increasing the charge on the projectile, or increasing the magnetic field.

Let’s say for example we want to hurl a payload of the same mass that a Soyuz-2 rocket can lift to low earth orbit, which is about \(8000 \unit{kg}\) for a Soyuz 2.1b. We then need the product of the magnetic field and charge to be about \(31.4\unit{kg\,s^{-1}}\).

The maximum magnetic field strength used in the LHC is about \(7.7\unit{T}\). With this magnetic field strength, the charge on the payload needs to be about \(4\unit{C}\). This is a large, but not impossible charge (the Coulomb is a surprisingly big unit of charge). You would have to take care not to let that charge leak away.

A major problem is that the LHC beam is tiny, whereas we need to maintain a uniform \(7.7\unit{T}\) magnetic field across the entire charged section of the spaceship. Furthermore, the moving charge will radiate away energy as electromagnetic radiation, resulting in losses of energy. So an LHC style accelerator is probably not reasonable.

I’m not sure what the maths looks like for curved railguns or maglev trains on curved tracks, which are more realistic than a highly electrically charged spaceship.

Another issue is that your spaceship will lose a significant amount of energy punching through the atmosphere. I’m not sure exactly how much, and it of course depends on how steeply the track tilts before launch. And you will be launching at orbital speeds rather than slowly gaining speed as you pass through the atmosphere, so you will face the same sort of heat concerns as a re-entering spaceship, except even worse because the atmosphere will be even more dense at launch altitude.

To attain orbit, a space gun would not be enough - you would also need to carry a rocket to make a circularisation burn at the apoapsis of your orbit, or else your orbit will return to the launch point - but you will lose energy reentering the atmosphere, and therefore in practice land somewhere a long way short of the launch point.

For further considerations on space railguns (with a view to hitting the moon), I wrote a post some time ago, albeit concerning linear space railguns.

Despite all these problems, apparently there are at-least-somewhat-serious proposals to build a space gun, also known as a mass driver. Some proposals seem to involve a hybrid of a few launch systems: the space gun may involve both a circular and linear track and does not attain the full orbital velocity, but shaves off some of the delta-v needed by a conventional rocket.

Mass drivers seem to be particularly popular as a hypothetical way to launch on the moon: the required velocities are lower, and you don’t have a significant atmosphere to contend with. Here is one such proposal for a ring with a radius of about \(100\unit{km}\) and a maximum RCF of \(3g\).

Comments