originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/148291...

This is the first post in a series to try and cover all the main concepts of flying rockets around in space in a reasonably accessible way.

I am, sadly, not an astronaut, but I’ve done most of a physics degree, and Kerbal Space Program has convinced me that rocketry can actually be really simple and intuitive. Hopefully these posts will be helpful if you want to write about science fiction spaceships or the like.

Why are rockets a thing?

On Earth, if we want to move somewhere, we can do so by pushing off something else: the ground (for walkers, cars, etc.) or the air (for aeroplanes, birds, etc.). In space, there is nothing to push against.

There are, basically, two options. Either you can push against what little there is (such as sunlight, or a huge laser array back home), or you can shoot part of your spaceship away from the rest of it, causing the remaining parts of the spaceship to move in the opposite direction. All space engines, not matter how complicated, amount to doing one of these two things, usually the latter.

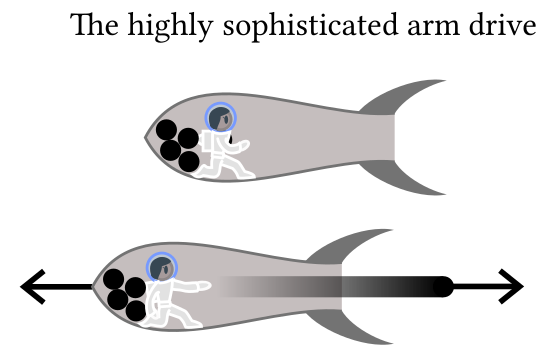

Here’s a very simple illustration “rocket”: the arm drive. An astronaut picks up bowling balls in throws them out the back of her rocket. This makes the rocket go forwards.

Jargon: the stuff that you throw out the back of your rocket is called reaction mass. This is distinct from fuel which provides the energy, though in the case of chemical rockets, the fuel and reaction mass are one and the same.

You use a rocket to change your velocity. Velocity is a thing that combines speed and direction: an object going 5 metres per second north, and an object going five metres per second west have the same speed but different velocities.

The good news about being in space is that nothing is going to slow you down. On Earth, friction and air resistance always conspire to make anything moving relative to the surface of the Earth, or at least to the air in the case of an aeroplane, slow down and stop. In space, there is nothing. So whatever your velocity is, it will stay the same unless affected by gravity.

So a rocket consists of two parts: the thing that you actually care about (sometimes called the payload) plus the structure of the rocket, and ‘reaction mass’ which will be launched out of the rocket to change its velocity.

Mass ratios and the almighty rocket equation

OK, here’s where it gets sticky. When you turn on the rocket, it doesn’t just have to move the rocket, but also all the reaction mass you’re still holding on board to throw out later. So the amount of reaction mass you need to change your velocity by a certain amount increases much faster than the velocity change you want to make.

Some more jargon: turning on your rocket to change your velocity is called a burn. The ratio of the mass of the rocket at the beginning of the burn \(M_i\) to the mass ratio at the end of the burn \(M_f\) (after losing some reaction mass) is called the mass ratio. The change in the velocity of your rocket is called the delta-v (“delta vee”), or \(\Delta v\).

(Reason for the name: the greek letter Delta \(\Delta\) represents a change in something: \(\Delta v\) is “change in \(v\)”. \(v\) is the usual symbol for velocity.)

There’s an equation called the Tsiolkovsky Rocket Equation which says that the change in the velocity of a rocket after a burn depends on the exhaust velocity \(v_e\) and the mass ratio \(M_i/M_f\) according to $$\Delta v = v_e \log \frac{M_i}{M_f}$$What this means is that the mass ratio is exponential in the delta-v: if you want to change your velocity by twice the amount, you need the mass ratio to increase by a factor of 7.4; if you want to change your velocity by three times the amount you need to increase your mass ratio by a factor of 20.1; it quickly becomes ridiculous.

If you’d like to know more about the maths, I work through the derivation of the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation and its relativistic counterpart here.

Practically speaking, only so much of your rocket can consist of reaction mass. The Saturn V used in the Apollo moon missions had a mass ratio of about 60, meaning 60 times the mass of the payload (the various modules used at the moon) was expelled either as reaction mass or as spent stages. In other words, the vast majority of material in your rocket is not actually useful, but just going to be thrown out the back.

This also places harsh limits on the amount of mass you can carry. Every kilogram of stuff you carry in your rocket requires you to carry tens or hundreds of kilograms of reaction mass to get the same delta-v. Rockets must be as light as possible and there’s no real way around that.

The two important numbers: thrust & specific impulse

To improve the amount of velocity change you can get from a given mass ratio, the only thing you can do is to increase the exhaust velocity, also known as your specific impulse (a name coming from the fact that it’s the force divided by the mass flow rate, 'specific’ being used by scientists to mean 'per unit mass’).

A chemical rocket, though easier to build than other kinds of space engine, has a relatively low exhaust velocity, around \(4,000\unit{m s^{-1}}\). Other propulsion systems, such as ion drives, can achieve much higher specific impulses; Wikipedia offers around \(30,000\unit{m s^{-1}}\) for a typical ion thruster, or more for more speculative designs such as the VASIMR.

The drawback of ion thrusters, and some other high specific impulse propulsion systems, is that they have very low thrust. Thrust is the other measure of a rocket: it’s just how much force a rocket applies to the ship when it is running, and hence how quickly it changes the velocity (the acceleration - note unlike everyday use of 'acceleration’, to physicists 'acceleration’ includes both changes of speed and direction). A low thrust rocket can achieve the same changes in velocity as a high thrust rocket, but it takes much longer to do it.

So in general the change of velocity in a burn depends on the thrust, mass of the rocket, and the duration of the burn.

In the distant future, much more speculative designs exist such as fusion rockets that have both high thrust and high specific impulse. But presently we are forced to choose.

High thrust is very important when leaving the ground. But we will come to that later.

Spaceships have their engines turned off most of the time

Because mass ratios increase so quickly, rockets can only change their velocity by so much before they expend all their reaction mass. This is called the delta-v budget of a mission.

Following the metaphor, a spaceship will 'spend’ its delta-v budget to perform maneuvers. Maneuvers - such as changing from one orbit to another - have a certain delta-v 'cost’.

The rest of the time, the rocket is inactive. Generally the rockets will only burn for a tiny portion of the mission.

This is unintuitive, since we’re used to Earth vehicles which are constantly losing energy to friction and air resistance, and therefore must have their engines running all the time. Sci-fi films frequently decide they’d prefer to show spaceships with the engines glowing, even if the ship is not performing a maneuver.

(Low-thrust engines such as ion drives are a semi-exception, in that they must burn for much longer than high-thrust engines to complete maneuvers, as mentioned in the previous section. But they still only activate their engines when they are changing their velocity.)

Orbits

Usually your rocket is not just hanging out in empty space; there is something big and heavy such as a planet or star in the vicinity that will change its trajectory through gravity. So lets talk about orbits.

When there are lots of planets, moons, etc. around it gets quite complicated, but we can start from building up from the simplest case: when your rocket is orbiting just one thing.

There are basically two kinds of orbits we’re concerned about: elliptical orbits and hyperbolic orbits. There is a third kind, parabolic orbits, which we won’t worry about because they only occur in ridiculously specific circumstances.

Elliptical orbits (space eggs)

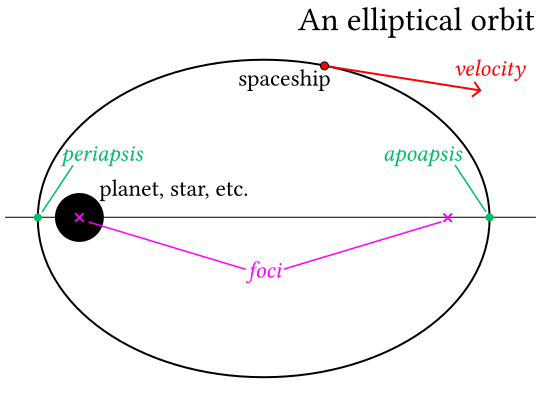

Elliptical orbits are what you’d generally think of as an orbit, as in, your rocket’s going round a thing. They look like this:

Mathematically, this is an ellipse with one of the two foci (singular 'focus’) on the centre of the massive object (planet, star, etc.). For simplicity’s sake, we’ll call the thing it’s orbiting a planet.

Elliptical orbits are characterised by a parameter called the eccentricity, which is usually written \(e\). The eccentricity tells you how how long and narrow the ellipse is. A circular orbit has an eccentricity of zero. An orbit with a higher eccentricity moves further away from the thing it’s orbiting, and back, over time. Elliptical orbits all have eccentricities between zero and 1.

There are two important points on an orbit: the periapsis and the apoapsis. (These have special names in some cases: for example if something is orbiting Earth we call them the perigee and apogee, if something’s orbiting the sun the perihelion and aphelion, etc.). The periapsis is the point on the orbit closest to the planet. The apoapsis is the point furthest away.

The second important parameter is the semi-major axis, usually written \(a\). This is just how big the orbit is: it’s half the length between the periapsis and apoapsis. For a circular orbit, the semi-major axis is the radius of the circle.

The periapsis is a distance \((1-e)a\) from the centre of the planet. The apoapsis is a distance \((1+e)a\) away.

The velocity of a rocket on an elliptical orbit is constantly changing, but its direction is always a tangent of the ellipse. And now an important point: the speed of a rocket is faster when it’s near the planet, and slower when it’s further from the planet. As the rocket comes in towards the periapsis, it picks up speed; as it moves out towards the apoapsis, it loses speed. This means the rocket spends a lot more time in the further away parts of the orbit than the nearby parts of the orbit. (The exact speed it has is precisely determined by for example the vis-viva equation, but I’m trying to avoid giving too much detail here.)

Here’s an animation to illustrate this principle:

[modified from this animation by Brandir on Wikimedia Commons; license CC BY-SA 3.0.]

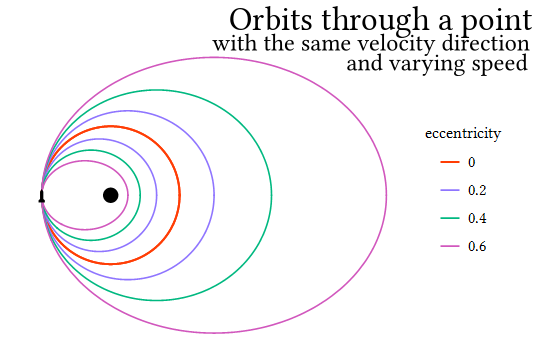

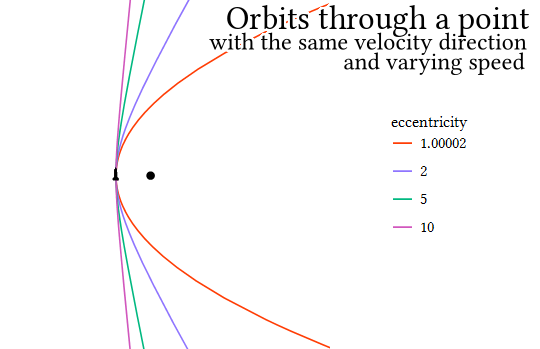

Which orbit does a rocket actually follow? It depends on its position and velocity: every combination of position and velocity corresponds to a different orbit. For example, here’s a picture of a succession of orbits that each pass through the same point in the same direction, but with different speeds. For some of these orbits, this point is the apoapsis; for others it is the periapsis. Dividing these two groups of orbits is a circular orbit. There are two orbits shown for each eccentricity, with different semi-major axes.

So far, we’ve been showing two-dimensional representations of orbits, all in the same plane. However, an orbit can be in any plane containing the central planet.

Astronomers have a number of different ways to describe orbits. In general, you need five numbers to pick out a specific orbit, and a sixth number to identify a position on that orbit. One way is to pick a position (three coordinates) and velocity (three components). Another important way is the Keplerian orbital elements.

Hyperbolic orbits trajectories

Hyperbolic ‘orbits’, or if you prefer hyperolic trajectories, are what happens when your spaceship is going too fast to stay in orbit. This is the course you follow if you’re escaping from a planet’s gravity, or if you’re doing a flyby.

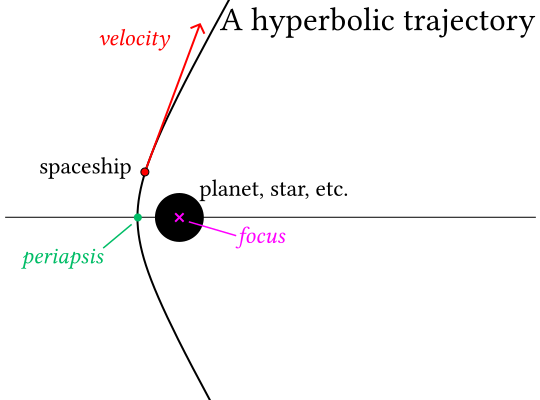

A hyperbolic orbit looks like this:

Mathematically, this is one of the two branches of a hyberbola. Like with the ellipse, its focus is on the centre of the planet. It has a periapsis, but no apoapsis. Many of the same rules apply: the spaceship gets faster as it gets closer to the periapsis, and slows down as it moves away.

As the ship moves further and further away from the planet in its hyperbolic orbit, it gets closer and closer (asymptotically) to moving on a straight line. This makes intuitive sense: in the absence of a planet, the ship would move in a straight line, and the planet’s gravitational influence gets less and less significant the further away you travel.

Like ellipses, hyperbolas have a parameter called the eccentricity \(e\). While for an ellipse, the eccentricity is always greater than or equal to zero, and less than 1, for a hyperbola it can be any number greater than 1. The reason both kinds of curves have this parameter is because hyperbolas and ellipses are both members of a family of curves called conic sections. (The parabolic trajectory, which we mentioned above but won’t discuss in detail, has an eccentricity of exactly 1. It’s nigh impossible to get onto a parabolic orbit in real life, and it’s pretty much the same as a hyperbolic orbit so we won’t worry about it.)

Here’s a quick summary of possible cases for the eccentricity:

- \(e=0\): circular orbit

- \(0<e<1\): elliptical orbit

- \(e=1\): parabolic trajectory

- \(e>1\): hyperbolic trajectory

For a hyperbola, the eccentricity basically measures how much the ship’s path curves around the planet. A spaceship following a hyperbola with a high eccentricity barely has its trajectory changed by the encounter with the planet. One with a low eccentricity can have its trajectory changed dramatically.

Like with an ellipse, the hyperbola also has a parameter called \(a\), again called the semi-major axis, though the reason for that name is less obvious. The periapsis is a distance \((e-1)a\) from the focus.

Here are some hyperbolic trajectories through a point:

The eccentricity can go as high as you like. The higher it goes, the closer it gets to a straight line. This corresponds to going very quickly past something very light that barely affects your course.

Energy & angular momentum: the unchanging numbers

Here’s a more mathematical bit.

So one important thing about orbits round a single thing like this is that there a two special things you can calculate at any point on your orbit, and you will get the same answer every time. These are the orbital energy and the angular momentum. Physicists will call these numbers conserved quantities.

These unchanging numbers have to do with the symmetry of the situation, which is something I will talk about in another post on Noether’s theorem at some point, eventually (if I keep promising to write this post, maybe it willl happen!)

Here’s the orbital energy $$E=-\frac{GMm}{r}+\frac{1}{2}mv^2$$where \(M\) is the mass of the thing you’re orbiting (keep calling it a planet), \(m\) is the mass of your rocket, \(r\) is your distance from the planet at a given moment, and \(v\) is your velocity at the same moment.

The first term is called the potential energy, and it gets more and more negative as you get closer to the planet. The second term is the kinetic energy and it gets bigger as you go faster. So as you go closer to the planet, your potential energy gets more negative, but your speed goes up by an amount that exactly counters that change so overall the total energy stays the same.

Divide out the mass of your rocket and you have the specific orbital energy (there’s that word specific meaning ‘per unit mass’ again). So the specific orbital energy is $$e=-\frac{GM}{r}+\frac{1}{2}v^2$$This is a handy quantity because it’s the same for anything on a given orbit, no matter how heavy the orbiting object.

The specific orbital energy is important because you can relate it to the size of the orbit, according to $$e=-\frac{GM}{2a}$$ for an ellipse, and $$e=\frac{GM}{2a}$$ for a hyperbola, where \(a\) is the semi-major axis in both cases. (This means an elliptical orbit has negative specific orbital energy, and a hyperbolic orbit has positive specific orbital energy). So an orbit with a lower specific orbital energy is smaller than one with a higher specific orbital energy.

The orbital angular momentum is $$L=\frac{1}{2}mr\dot{\phi}^2$$ where \(\dot{\phi}\) is the rate of change of the angular coordinate, basically a measure of how quickly you’re going around the planet without regard for how much you’re going towards or away from the planet. So as you get closer to the planet, you don’t just need to be going faster in general, you need to be going faster around the planet. But we won’t talk about this one so much in this post.

The point of this is: these numbers are unchanging over a given orbit. So you can think of rocketry maneuvers and other things that affect the speed of your rocket changing these numbers, and therefore changing the orbit you’re on.

If you reduce your orbital energy, you will generally be put on a tighter orbit that goes closer to the planet.

For example: if you are flying through a thin atmosphere, you will lose orbital energy. This will put you onto a smaller, tighter orbit with a lower orbital energy. You might quickly regain the speed you lost as you move down to a lower orbit, but you’ve lost orbital energy. Since the orbital energy is unchanging under most circumstances, it’s easier to talk about that than your speed, which is constantly going up and down.

Six directions

Right, here are the things your rocket might do.

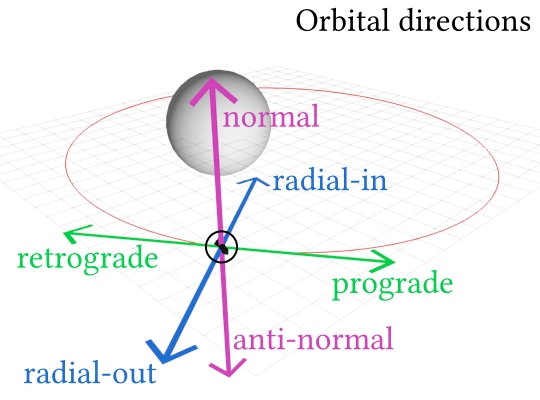

First of all we’re going to have to name some directions! The “mathematical” names are the terms used in the Frenet-Serret formulas. The other names are the ones used in Kerbal Space Program.

Prograde (mathematically, tangential) is the direction your rocket is going in in its orbit.

Retrograde (mathematically anti-tangential I guess) is opposite the direction your rocket is going in.

Radial and anti-radial, or radial-in and radial-out (mathemtatically, normal and anti-normal), are perpendicular to the direction of your orbit, in the plane of the orbit. It’s a matter of convention whether “radial” is inwards (roughly towards the planet) or outwards (roughly away from the planet). Kerbal Space Program uses the convention that “radial” is inwards. For clarity, I’m going to stick to “radial-in” and “radial-out”.

Normal and anti-normal (mathematically binormal and anti-binormal) are perpendicular to the plane of the orbit.

And yes, the makers of KSP decided to use a different meaning of the word “normal” to the Frenet-Serret thing.

These are independent of which way your rocket is pointing - they depend only on where you are, where the centre of the planet is, and which way you’re going.

Your rocket can in fact point in any direction. It does not have to fly “forwards” because there is no atmosphere to worry about streamlining. This is quite different from aircraft on Earth - an aircraft can fly in a way that’s not pointing straight forward, but it’s not usually a good situation to be in. A rocket, on the other hand, needs to point whichever direction is appropriate for the next maneuver, or to expose its solar panels to the sun, or spin to provide a sensation of “gravity” to the astronauts inside - all sorts of possibilities.

Since it can point in any direction, it can burn in any direction. But any burn can be broken into ‘components’ along these six directions. So we can talk about each of them individually.

The next post

We’re going to go into detail about the different directions you might want to burn in, and what they do to your orbit. And we’ll use that to talk about important maneuvers like circularisation burns, Hohmann transfer orbits, and how you go about making a rendezvous with another spaceship!

Comments