originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/120005...

Astrologically-minded people have been talking a bit about Mercury going into ‘retrograde’ recently.

I’m sure if you look you can pretty easily find an explanation of what that means in astronomical terms (I won’t try to speak to the astrological significance of it in whatever tradition you might subscribe to), but regardless I thought it would be nice to do a big long post about how the planets move around in the sky, how we know in advance what they’re going to do, etc.

This won’t be a post about the historical development of these ideas. I already did one of those. And I’m gonna include some maths, but also lots of words, so hopefully if you’d rather, you can just ignore all the equations!

OK, so what’s going on up there then?

So in general when you want to work out the answer to some question like “what are the planets up to”, physicists want to be able to start with the where the planets are at one point in time (this is called the “initial state”) and get a description which tells them exactly where the planets are at every particular time before and after.

That’s the ideal.

The general problem of a bunch of objects (three or more) moving around and interacting through gravity is “chaotic”. That means that our prediction of where the objects go next can change a huge amount when the initial conditions change. Because of this, you can’t in general get a nice straightforward set of equations that tell you what‘s going to happen.

So you have to make some approximations in your description of the system, and use a computer to predict approximately what will happen. If you’re lucky, your approximations won’t lose anything important.

The lucky thing about the solar system is that the sun is much much much bigger than everything else. So while each planet is attracted not just to the sun but every other planet in the solar system, the effect of the sun is vastly bigger than that of every other planet.

A very good approximation, then, starts by assuming the sun is the only thing that matters, and just ignoring all the other planets. That’s really the only way you can go if you don’t have a computer simulation handy.

Kepler’s model, which is what happens if the planets all ignore each other

(hamiltonianflow has done a very good series on this subject, which you can read here. So if you want a bit more mathematical detail than I go into, try her series!)

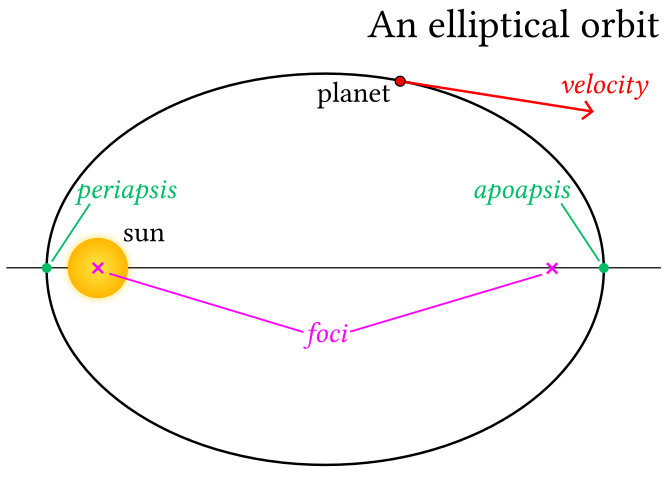

Here’s an example of the kind of shape called an ellipse.

When you only have two bodies involved - for example, a planet and the sun - each body orbits along an ellipse. (Or some other kind of conic section - but if it’s not orbiting along an ellipse, the planet will fly off somewhere very far away, so let’s not worry about that.)

Each pink cross is a focus (plural foci) of the ellipse. One definition of an ellipse is that if you take any point along the ellipse and add up the distances to the two foci, the total will be the same.

What’s important is that, for the ellipses that the objects two objects are moving along, each has one focus at a point called centre of mass.

The centre of mass is a point that’s nearer the more massive (heavier) of the two bodies (and bang in the middle of the gap if they’re the same mass). Now, the sun’s mass is \(1.99\times10^{30}\unit{kg}\). The mass of the heaviest planet, Jupiter, is \(1.90\times10^{27}\unit{kg}\). That means that the sun is a thousand times heavier than Jupiter; the difference between the sun and the other planets is even bigger. So the centre of mass is pretty much right in the centre of the sun, for every planet.

This means you can pretty accurately say each planet orbits along an ellipse, with its focus at the centre of the sun. (That’s called Kepler’s First Law, because Kepler came up with this model first.)

An ellipse tells you where the planet might be, but we want to know where the planet is at a particular time. Kepler had a complicated description that comes in terms of ‘areas swept out’ by a line between the planet and the sun. Nowadays, we treat it with various equations, though finding a simple equation to get the orbital state vectors as a function of time is surprisingly difficult!

But the important detail is basically that planets travel faster when they’re near the sun, and slower when they’re far away from the sun.

That particular relation - speed vs. distance from the sun - is expressed by quite a simple equation called the ‘vis-viva equation’,$$v^2=GM_\odot \left(\frac{2}{r} - \frac{1}{a}\right)$$In this equation, \(v\) is the speed of the planet, \(r\) is its distance from the sun, \(a\) is the semi-major axis which is a measure of how big the orbit is, \(M\) is the mass of the sun, and \(G\) is a constant that tells you how strong gravity is.

The third thing Kepler said is that the total time \(T\) that a planet takes to complete an orbit of the sun - its ‘year’ in other words - grows in a particular way depending on how far away the planet is orbiting:$$T^2=4\pi^2\frac{a^3}{GM}$$or the square of the period (year) is proportional to the cube of the semimajor axis.

So the length of the planet’s year depends how far away the planet orbits from the sun.

Those three rules are enough information to tell you exactly where the planets are going to be at any point in the future, assuming the sun is the only thing that matters.

So what about our planets specifically

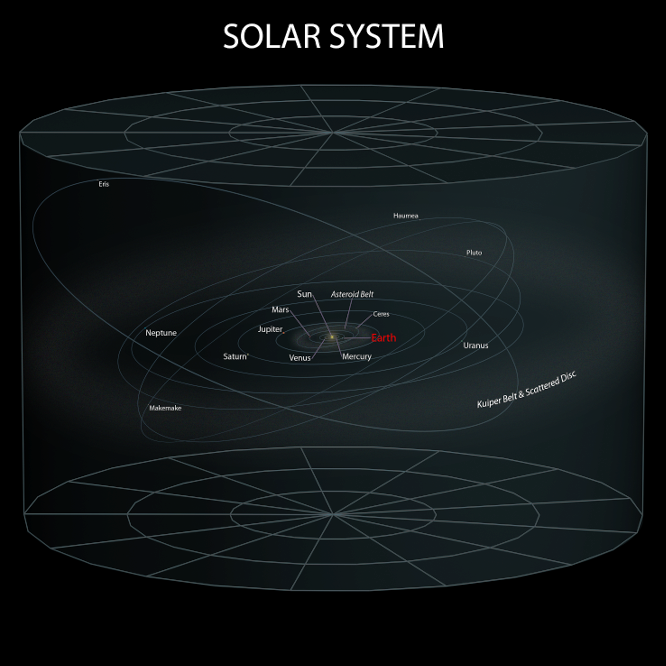

Our sun formed from a giant disk of gas and dust that slowly shrank under its own gravity around a dense core. Because of a principle called ‘conservation of angular momentum’, as the disk shrank, the tiny motions of the gas within the disk are increased to form a large, flat, rotating disk.

A lot of that disk is picked up by the growing sun in the centre, but the leftovers form small lumps which grow into bigger lumps as they collide with each other. These eventually form the planets and the asteroids.

The result of this process is that the planets all rotate in the same direction around the sun, and they all orbit in almost exactly the same plane. This plane is called the ecliptic.

The orbits of the planets in our solar system are not very eccentric at all either. The eccentricity of an orbit is basically a measure of where the ellipse falls on a continuum from ‘circle’ to ‘straight line’, so a more eccentric orbit is one that’s more stretched out. So in other words, the orbits of the planets are, despite being ellipses, very near circular. This is part of why models of the solar system featuring circular orbits were very effective.

As for why the eccentricities are so low, there are a few possible answers - interactions with the other planets, interactions with dust in the protoplanetary disc, tidal interactions with the sun - but it’s still an area of active research.

The sun is not the only thing that matters

You can get away with ignoring the influence of the other planets over a few centuries, but eventually the effects of their small gravitational pulls starts to add up. Which leads to surprisingly large consequences for things like the climate of the Earth!

Because the sun is still the most important thing in the picture by far, we usually look at these orbital peturbations as modifications to the picture we just described.

These can come from a few things:

- the other planets (the big one!)

- things not being spherically symmetrical

- things getting caught up in atmospheres

- General Relativity

Because a lot of the causes of these peturbations (i.e. other planets coming near) are periodic - they happen regularly with the same time between them - the peturbations are also periodic. (The planet Neptune was discovered as a results of the small periodic peturbations it was causing to the orbit of the planet Uranus).

For planets’ moons - particularly the Earth’s Moon - things get flipped round: the Earth is the main thing in the picture, but the sun causes the biggest peturbations and changes the Moon’s orbit quite significantly over time.

It is also the case, in theory, that these peturbations can add up and throw a massive spanner in the nice neat orbits we’ve been talking about so far, leading to planets colliding with each other.

We can ask if, over millions and millions of years, the behaviour of planets in the solar system is stable (i.e. the only changes are the small peturbations, but everything remains much as described above). The answer is: we know pretty much exactly everything that’s going to happen over the next few million years, and we don’t have to worry about colliding with a planet.

For the next few billions of years, things are probably going to be ok, but if we give it five billion years, there’s a tiny chance that Mercury’s orbit will go wildly unstable, either plunging it into the sun, colliding it with Venus, or disturbing Jupiter in a way that fucks up the orbits of all the inner planets so we could collide with just about any of them. Fun. In any case, after that 5 billion year point, the sun will run out of hydrogen to effectively fuse in its core, and grow into a red giant star, swallowing up the innermost planets and destroying any remaining life on Earth.

(For comparison: life on Earth has existed for about four billion years, and we humans have been around for 50k-100k years, which is to say, 0.0025% of that. It is near certain that all humans will be billions of years dead by the time Mercury and the sun get around to doing any of those things. And if by some impossibility we have not, I would expect us to exist on other planets apart from Earth. So don’t worry too much :3)

One thing on that list, general relativity, only gets really important when you get near the sun. The very brief explanation is that Newtonian gravity is actually only an approximation itself to a much more mathematically complicated theory. On the scale of the solar system, that mostly doesn’t matter, but it does have a small but noticeable effect on the orbit of Mercury! That effect is one of the lines of evidence that formed some of the earliest experimental tests of the theory, so I thought it was worth a mention.

As for the climate thing - well, the peturbations to the Earth’s orbit and the way in which its spinning are generally periodic, repeating over thousands of years. Examining long-term historical climate data revealed these incredibly slow changes (exaggerated by feedback effects) lead to similar periodic changes called Milankovitch cycles in the Earth’s average temperature. Probably. This science is perhaps a bit less settled than some of the rest of this post.

What do we see of all this from the ground?

Since most of the people reading this post are probably on the surface of the Earth (any astronauts and/or extraterrestrial lifeforms reading, please say hi!), if we want to observe the planets, we look up at the night sky for little bright dots that look very much like stars. (If we are lucky enough to have a good telescope, we can resolve these dots into flat disks with some surface variation.)

Most of the things in the sky, as watched by human eyes from Earth, don’t do much, day to day and month to month. They sit in a fixed pattern in relation to the other stars. Now we have telescopes, we can notice that isn’t quite true - some of the more nearby stars move a bit over the course of the year due to ‘stellar parallax’ which lets us work out how far away they are, and some stars are moving through space quickly enough to notice in a telescope (particularly the stars orbiting the black hole Sagittarius A* at the centre of our galaxy!).

The planets are not like these ‘fixed stars’. They don’t stay in a set position compared to the fixed stars. The English word “planet” is derived from a Greek word meaning “wanderer” for this reason.

When something is odd and moving about, a natural thing to do for people across the world was to keep track of where it is each night. And if you do this, you can see the planets slowly make their way from place to place in the sky, reflecting their motion in space. Planets close to the sun, like Mercury, generally move much faster than planets far away from the sun, like Saturn. (Uranus and Neptune are harder to see without a telescope.)

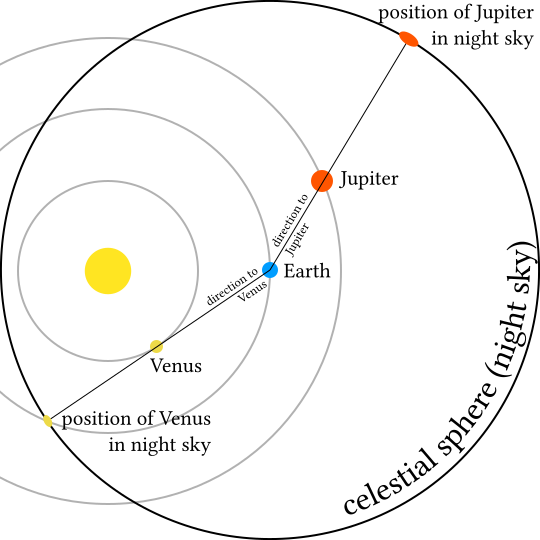

We can imagine the fixed night sky as being an enormous sphere centred on the Earth, with all the “fixed” stars as little dots attached to it. This is helpful for describing how the planets move in the night sky. (The sphere is basically a map of the angular direction of each star from the centre of the Earth.)

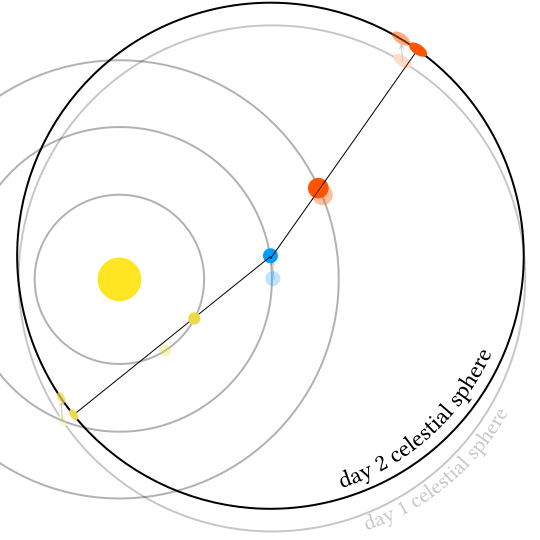

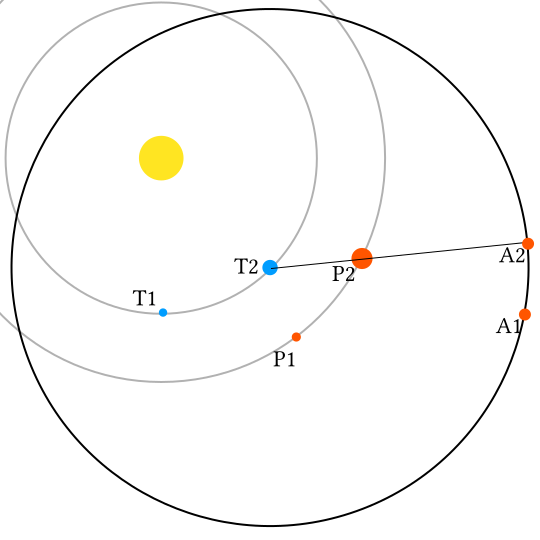

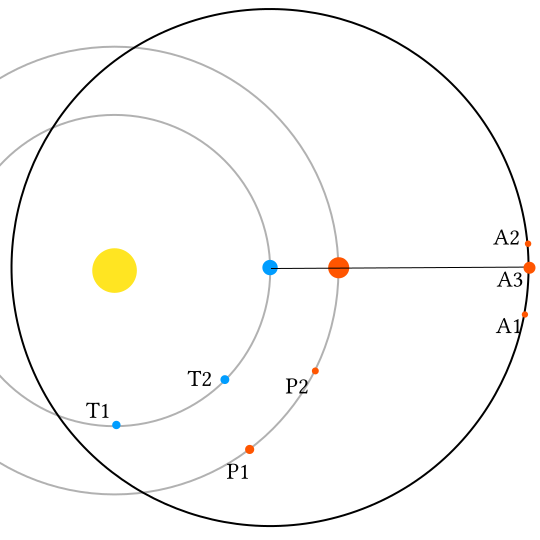

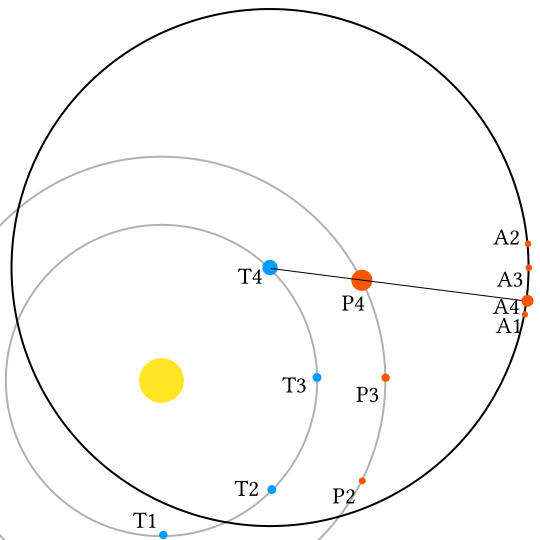

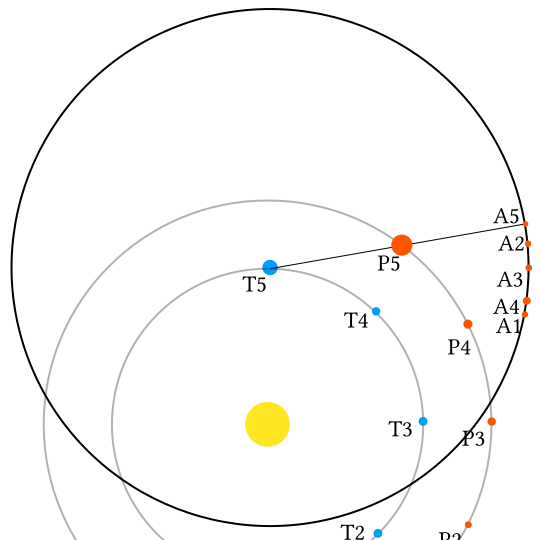

So in this picture, the Earth is sitting in the middle of the frame, with the celestial sphere centered on it. I’ve drawn two planets, and two lines through those planets to the celestial sphere, to show how the positions of planets in the celestial sphere is determined by the relative positions of these planets.

How do the planets move? Here’s a picture where I’ve drawn this diagram for two different days, one over the top of the other…

The positions of the planets on the first day and its celestial sphere is faded out slightly. I’ve also drawn the day-1 positions of the planets on the day-2 celestial sphere, again faded out. I’ve made Venus move further than Earth move further than Jupiter, but I’m not doing this at all exactly.

Now all three planets have moved around the sun, both Jupiter and Venus have moved to slightly different places on the celestial sphere.

That’s the general principle of how planets appear to ‘wander’. You can see it’s pretty complicated.

Now, a very large part of the motion, especially for the inner planets, comes from the Earth’s own orbit. Because of the Earth’s orbit, these planets appear to travel all the way round the night sky over the course of a year, even though their movement in space is much smaller than that of the Earth. This is why it made a lot of sense to people, at first, to say the planets travelled round the Earth.

Because the planets’ orbits are largely confined to a plane (the Ecliptic mentioned above), they all pass through roughly the same areas of the night sky. As a result of the Earth’s motion, so does the sun. (Based on this property, the predominant Western astrological system divides the night sky into 12 equal-sized regions, into which the planets pass over the course of a year. Patterns of stars in each of these regions (as seen from Earth) give each one its symbolism).

And retrograde motion?

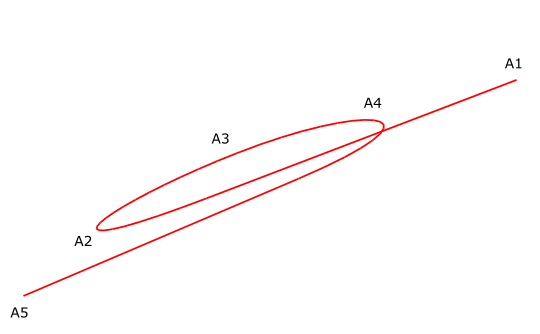

One of the interesting aspects of living in a heliocentric solar system like this is that, on occasion, the planets seem to temporarily change the direction of their motion relative to the fixed stars in the night sky. They can follow a pattern such as this over the fixed stars:

(this squiggle shows the motion of Mars in 2009-2010, via Wikimedia commons)

This presented a big headache to people trying to work out a geocentric model of the solar system (one in which everything rotated around the Earth) according to Aristotle’s principle . In a heliocentric solar system, such as Kepler’s one described above, there is a straightforward explanation, though the situation looks slightly different for planets orbiting inside the Earth and planets orbiting inside.

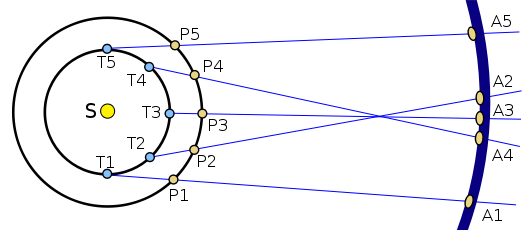

For outer planets such as Jupiter, the situation is this: Jupiter is sedately carrying on its orbit, and the Earth zooms past on the inside.

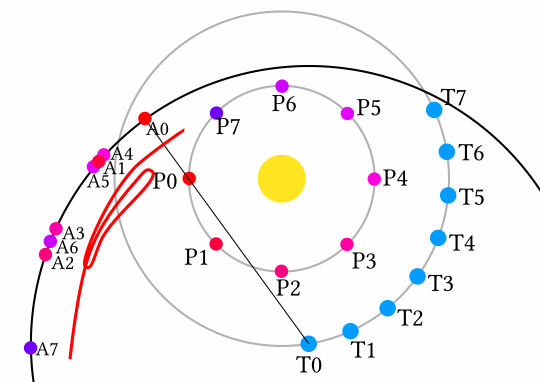

This image (by Rursus on Wikimedia commons) shows the positions of two planets, the Earth (the ‘T’ planet) and another planet (’P’) as well as the other planet’s position on the celestial sphere, at each of five points in time over the coures of half an Earth year. Unlike my diagrams, Rursus has centred the celestial sphere on the sun, and not the Earth. The difference stops being important as you make the celestial sphere bigger, and it does make it a lot easier to show everything on one diagram.

Anyway, as the inner planet moves up towards the outer planet, they are moving at quite different angles, so the outer planet appears to move a large distance on the celestial sphere. As the inner planet catches up, being faster, the outer planet appears to move ‘backwards’, until eventually the inner planet is moving more or less directly away from the outer planet and it appears to move forwards again.

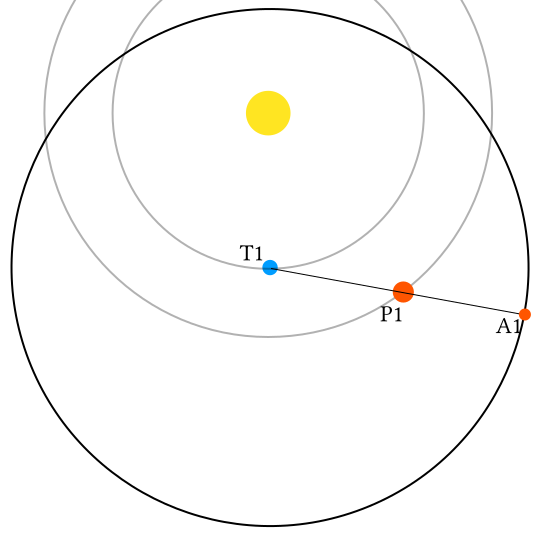

To show that this still happens if we use a properly Earth-centered celestial sphere, I did a series of images :)

…which, however rough they are, hopefully show the general principle.

For a very slowly moving outer planet, this happens nearly every Earth year. For a more quickly moving planet such as Mars, it will happen slightly less than once a year.

For the planets closer to the sun than Earth (Mercury and Venus), you can essentially draw the reverse of this diagram, fixing the outer planet in the frame as your ‘Earth’ and drawing lines through the inner planet. That said, to see retrograde motion when I tried this, I had to tune the speeds a little bit - but with the rigt speed, it can be quite pronounced. (I’m not going to post the whole series, but this image was constructed the same way as the last set!) The red squiggle is a rough trace of the positions visited in order, in order to make the retrograde motion clearer.

Anything else I should know about those planets?

While I was talking, Neptune stole your wallet. Sorry.

More seriously, there’s a lot more mathematical detail to be had if you want to learn more about the planets. I represented stuff as 2D circles and the celestial sphere as a circle, but of course we live in 3D space (3+1D spacetime if you want to get all relativistic on me), and the sky forms a 2D plane, so you have to invoke a lot more parameters to describe the motion of the planets of the sky in all its precise grisly detail. To fully describe an elliptical orbit, you need six numbers. To precisely state the position of objects in the sky (in terms of “point your telescope here”), there are many coordinate systems. Like, really a lot.

Also I guess… I have no wish to be the ‘no fun allowed’ person, but if you’re genuinely worried about Mercury going into retrograde (I can never tell quite how serious people are about that, but… I know what it’s like to have anxiety :/), astronomically there’s nothing more going on at present than an interesting visual effect that becomes apparent if you very carefully keep track of the position of Mercury in the sky over a long period of time. There’s no special reason why things are more likely to go wrong while Mercury and the Earth are in these particular parts of their orbits.

Comments