originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/113281...

In ancient Greece, the philosopher Aristotle decided, basically for the aesthetic (it’s more complicated than that, I know, shhhh), that celestial bodies ought to move in circular paths, centered on the Earth, as if attached to gigantic crystal spheres.

After his death in Ancient Greece and later the rest of Europe, Aristotle was generally thought to be the shit, and if he said circles, circles it should be. Unfortunately, the planets seemed not to behave the way you’d expect if they were travelling smoothly along circles around the Earth. Every now and then, they would slow down and move backwards, tracing out a little loop in the sky.

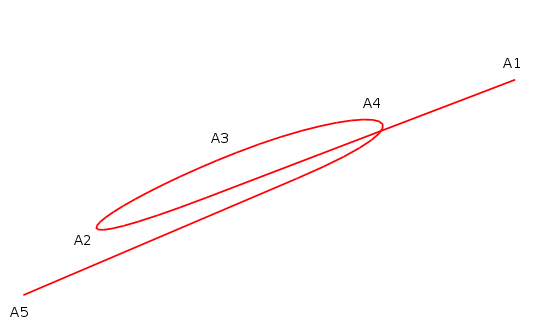

For example, here’s the apparent motion of mars in the sky in 2009-2010, relative to the background stars (source)…

To get around this problem, the people, such as the Greek philosopher Ptolemy, who were trying to predict the positions of the planets had to add some component to their models. You could imagine Aristotle’s original model as a bunch of big wheels, called deferents with their hubs on the Earth… or at least near the Earth. The idea of an epicycle is basically to add another, smaller wheel attached to the rim of the outer wheel, with the planet attached to that. That way, the combined motion of the deferent and the epicycle could make the planet appear to move backwards, or speed up and slow down at different points in the planet’s orbit. And that actually worked really well.

But with precise measurements of the positions of planets relative to the background stars, even that wasn’t enough. So the people doing these calculations had to add more epicycles attached to their epicycles.

Epicycles work on a principle similar to Fourier series. Though, to make sure no historians of science jump out and eat me, they’re not actually Fourier series; but like with Fourier series, by stacking enough epicycles on top of each other, you can basically get a planet to do anything you want.

There were a lot of models floating around in ancient Greece, but the Ptolemaic model is the one that stuck around. It was only much much later in the 1500s that a guy called Copernicus showed up with the idea that maybe the Earth is not at the centre of the solar system (and indeed the universe) - instead all the planets orbited in circles around the sun.

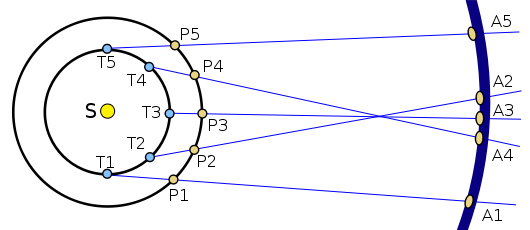

This offered an explanation of apparent retrograde motion instead of epicycles: if the Earth overtakes a planet that is orbiting on a larger-radius orbit, the planet appears to move backwards relative to the faraway stars. (source)

However, Copernicus’s model didn’t really catch on, and for pretty good reasons. Copernicus’s model, in which the planets still moved on circles, didn’t need epicycles to explain apparent retrograde motion, but it still needed quite a few epicycles and didn’t really offer any better predictions. (Though predictions were only partly the point - apparently there was a division between the people who did the calculations, and used a lot of epicycles, and the supposed philosophical truth, which still went with what Aristotle said. I think, this is half-remembered from a history and philosophy of science course I sat in the lectures of a few years ago!)

Tycho Brahe, as mentioned, took a bunch of very very very precise measurements of the planets around the end of the 1500s - without a telescope! From this, he found the Ptolemaic system (and the Copernican system) just weren’t good enough to predict the motions of the planets, and came up with a sort of weird hybrid system in which the sun orbits the Earth, and the five known planets orbit the sun. But still with circles for the orbits. Galileo, meanwhile, was arriving on the scene and making waves with his telescope opservations. He discerned phases of Venus like those of the moon in the early 1600s, which generally ended things for any system but the Copernican and Tychonic systems. Tycho’s system was kind of troublesome for Aristotle’s crystal spheres, but it was still (apparently) more intuitive to people in the early 1600s.

To emphasise, during this time, it wasn’t obvious that either model was inherently better. Galileo pushed the Copernican system hard, and the Pope asked him to write a book on the subject, expecting him to ultimately favour Tycho’s system. His book ended up apparently really heavily mocking the Pope, who up until that point had been one of his few allies (Galileo had a habit of pissing everyone off). For his trouble, Galileo ended up under house arrest, and the Catholic church - previously kind of neutral on these things - put itself definitively in favour of the geocentric/Tycho side.

So around this time, Kepler, who had been an assistant to Tycho, does a bunch of calculations trying to find a better model. Kepler concluded that he could fit the motion far better if the planets moved on ellipses instead of circles given a few rules. The sun would be at one of the focuses of an elliptical, and the speed of a planet moving along the ellipse would be such that if you draw a line from the sun to a planet, and calculate the area swept through by that line in a certain amount of time, it would be the same regardless of where the planet was in its orbit.

And this model was great. It didn’t need anything ugly like epicycles (and being heliocentric could account for apparent retrograde motion), and it was a much better predictor of what people saw in the sky than the other models of the time. Using his ellipses model, Kepler managed to predict when Venus would move in front of the sun, which was a big deal. Kepler was on to something…

What Newton did with this is a story in itself, and you can read more about in What IS the canonical momentum?. And if you’d like more detail on how the planets move, you may enjoy this post.

Comments