originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/687244...

That manga… No… too large to be called a manga…

Hello once more my friends! Happy Thursday. It’s finally time for Berserk!

So. Today we’re going to be looking at one of the adaptations of Berserk - not the renowned 90s TV show, although I will tuck in an episode of that, but the movie trilogy by Studio 4°C that ran from 2012 to 2013. But first! Let’s talk about the manga…

What has not been said about Kentaro Miura’s genre-defining epic? Probably very little, but that’s never stopped me before!

So. Berserk is a ‘dark fantasy’ manga series that ran from 1989, when Kentaro Miura was just 23, until his death in May last year - a span of 32 years. At this point I have read up to

The story has gone, as you’d expect, many different places, but broadly it is a projection of the horrors of the European Wars of Religion into a heightened fantasy world - all centered on the character of Guts, a badass traveling swordsman who, marked for demonic sacrifice, persists in the world out of sheer stubbornness and battles the demonic ‘Apostles’.

The real meat of it begins with the Golden Age arc, the point where we see just how great a storyteller Miura really is. He precisely lays out a kind of grand Shakespearian tragedy, following Guts’s growth to adulthood with a mercenary band led by the iconic ambitious (evil) femboy Griffith, and the grand betrayal that set him on the present path. Even though we have some idea how it will end, the story rolls on with a feeling of terrible inevitability.

One of the great strengths of Berserk is the sheer variety of emotional tones Miura can convey. It is of course best known for its incredibly vivid and detailed battle scenes, the splattery panels of people being hacked apart by swords - and certainly Miura is one of the best at composing action, and a ludicrously methodical illustrator. Berserk loves to deliver the spectacle of, say, a massive cavalry charge…

(Look at all these horses in distinct, active poses and dynamic perspective, the use of value in the composition to make sure it reads, the sheer amount of effort put into precise hatching around the muscle shapes of each horse. I can only imagine how long it took to draw just this one panel.)

But more than that, Miura is capable of portraying moments of painful tenderness and wicked humour. The Golden Age arc wouldn’t work nearly so well if we didn’t feel the sense of camaraderie in the Band of the Hawk, watch Guts warm up to them, or even ourselves come to believe in Griffith’s dream. The horror of the eventual climax at the Eclipse depends on all of these moments leading up to it.

Yet that’s only the first quarter 100 chapters or so of a manga that has so far reached around 364 (with Miura’s assistant Kōji Mori now set to continue). Following this point, the story enters the Conviction arc, beginning with relatively self-contained stories but building up into a new story about a depraved inquisitor. Miura has a good eye for turning these stories into not just a monster of the week, but compelling self-contained story in its own right (usually a very sad one!), embedded in an overall arc of the traumatised Guts cracking his cynical shell and slowly growing to once again accept connections to other people and become more of a protector figure.

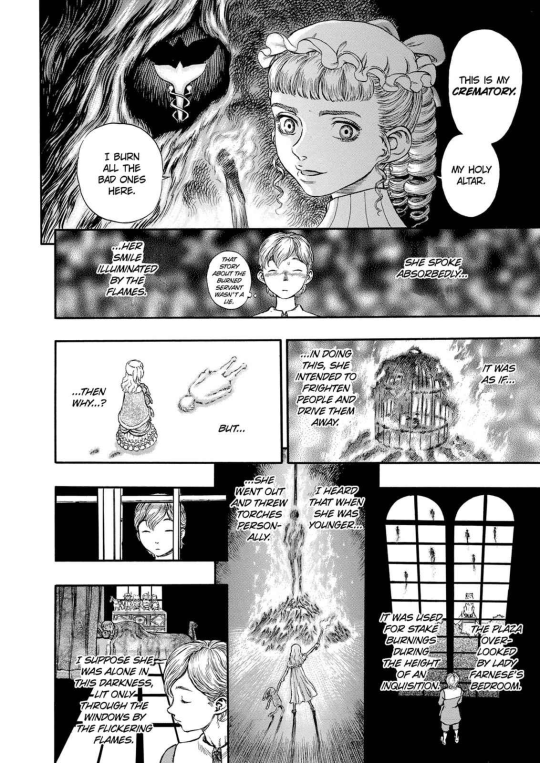

So by the following Falcon of the Millenium Empire arc, the central cast has expanded considerably: Guts, now on a mission to heal his wife Casca who has been traumatised to the point of taking on a totally childlike demeanour, gradually finds himself joined by a whole party. Puck the elf (here more like a fairy than a LotR elf) is a fourth-wall-breaking Greek chorus present from the start; alongside him arrive Isidro, a young boy who idolises guts and tends to form the comic relief; Farnesse, once an aristocratic witch-hunter fascinated by flames; Serpico, her loyal retainer and secret brother; eventually even Schierke the young apprentice witch and her own elf companion Ivalera.

One of the biggest concerns of Berserk is to show how these various characters came to be as they are, and show the events unfolding as a chain of causality. Every so often, we’ll dive into a flashback to flesh out one of the central characters, and honestly these tend to be some of my favourite parts of the story.

This idea of causality is actually explicitly discussed by characters like the mysterious Skull Knight, implied to be something of a predecessor to Guts who seems to have a sense of how the plot will unfold; Guts is described as existing outside the chain of causality by virtue of being sacrificed - and though he has become a kind of homo sacer to be killed with impunity by demons, this also gives him the opportunity to intervene in events. But how is in question; Guts is torn between two impulses: his desire for revenge on Griffith, his desire to protect Casca and the others who came under his wing, mixed his fear about hurting people in rage and bloodlust during fighting.

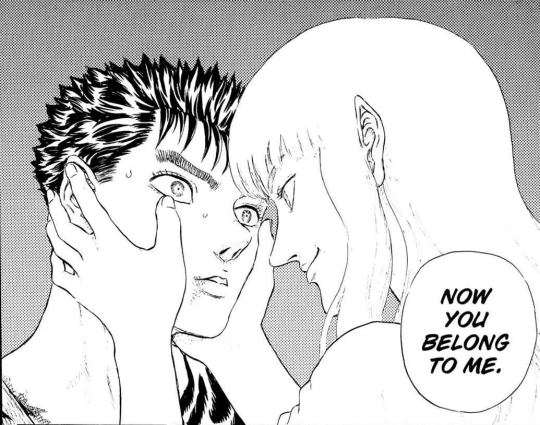

All this must sound very macho, and yeah, it often is - but right from the very start of Berserk it’s balanced by symbols of effeminacy as well, whether in the form of Puck the neotenous elf (who the camera loves to linger on) or, of course, Griffith - and the relationship between Griffith and Guts is very heavy on sexual tension…

So, wherever did all this come from?

Prior to Berserk, I don’t believe this particular kind of fantasy manga was well-established. Certainly pretty much all subsequent works in the ‘dark fantasy’ genre, from other manga like Claymore (2001-2014) to games like Drag-on Dragoon (2003) and Dark Souls (2011) cite it as a massive influence.

In the 80s, Western fantasy works were enjoying a wave of popularity, particularly in computer RPGs attempting to capture the experience of D&D - which of course ended up with quite a different lineage in Japan (a divergence exemplified by the Wizardry series, which spawned a completely different line of sequels in Japan and the West). And by this point, Dragon Quest (1986) and Final Fantasy (1987) were on the scene; there was a big interest in fantasy art. However, the tone of these games was quite different, targeted much more at children.

Here we’ve got to tread a little carefully to avoid muddying the picture! When we talk about the ‘grimdark’ movement of Western fantasy novels that kicked off with A Song of Ice and Fire in 1996, there’s a narrative that claims all prior fantasy was highly moralistic and full of uncomplicated romantic heroes, but thanks to authors like Martin, there was a turn to cynical realpolitik, bloody violence and torture, and sex (and in particular lots of rape). But it’s not true; this narrative erases the whole ‘sword and sorcery’ and ‘dying earth’ subgenres from existence; in fact there has been ‘dark fantasy’ pretty much from the start, at the very least from the 1960s. Such works, particularly the writing of Jack Vance, Poul Anderson, Michael Moorcock, and (sigh) yes Lovecraft and Howard formed a major part of the fabric of D&D in 1974.

And indeed, Miura cites two major sword-and-sorcery works as part of his inspiration for Berserk’s setting: the 1982 film adaptation of Howard’s Conan the Barbarian (featuring Arnie!) and Moorcock’s Elric of Melnibone series. I think the Elric connection would be very interesting to develop, because Moorcock was definitely interested in the same sort of grand themes as Miura, but I’ll have to actually read it first lmao…

Alongside this, Miura cited some other works from the West, namely the films Mad Max (you can kinda see it) and Star Wars (bwuh?).

Of course, Miura also had plenty of influence within manga. Buronson and Tetsuo Hara’s post-apocalyptic fighting manga Fist of the North Star (北斗の拳, 1983-88) frequently comes up as a big influence, and we can certainly see the resemblance between Kenshiro (above) and Guts, as well as the general post-gekiga art style full of heavy hatching and intricate, thin lines that Miura would pick up so well.

Alongside that, Miura’s demons unsurprisingly owe a lot to Go Nagai; he also heavily praises Osamu Tezuka’s historical manga Dororo. But there’s actually another line of influence that may or may not be surprising: shōjo manga, particularly that of the Year 24 Group…

Miura commented about the influence of shōjo manga on the series, stating that it is about “expressing every feeling powerfully.”[17][23] Particularly, he mentioned influence from Yumiko Ōshima,[17][23] and that the anime adaptations of The Rose of Versailles and Aim for the Ace!, both directed by Osamu Dezaki, inspired him to read The Rose of Versailles manga and the works of Keiko Takemiya, notably Kaze to Ki no Uta.[16][24]

Dezaki we covered previously on Animation Night 95, and we watched the anime adaptation of foundational yaoi manga Kaze to Ki no Uta back on Animation Night 69 - and, like, yeah! You can certainly see how Griffith in particular, with his flowing curly hair and pouty lips, looks like he comes straight from a shōjo manga - something perfectly fitting the larger-than-life charismatic hero role he assumes. And in general, this old school shōjo approach to storytelling proved an absolutely perfect fit for the quieter, emotional parts of the story: repeated lines to establish a certain cadence, panels which don’t show events but just establish mood, a certain wistful beauty.

It is the contrast between these two elements that makes Berserk sing. It invites you to indulge in its gleeful fascination with fever-dream ultraviolence but it’s also very determined in observing its consequences on the survivors.

Surely the most controversial aspect of Berserk is how frequently it portrays rape. Make no mistake, it is quite a lot, and if you do not want to deal with that, just don’t read Berserk.

So, how exactly does it go about this? Notably, the main three characters of Berserk are all survivors of sexual violence. Guts was betrayed by his father-figure early in life; Casca was rescued from rape by a noble by Griffith; a young Griffith did deeply traumatising sex work for a different noble to fund the Band of the Hawk in its early years. All three of these events, while they might be a bit absurd and melodramatic on some level, are treated with a great deal of care and gravitas - in particular, the arc of Guts and Casca sharing their respective stories and growing closer together and creating a more positive form of sexuality is one of the most affecting parts of the Golden Age arc, frankly the best het scene I’ve ever read lmao.

Furthering that approach is effective use of rape as an element of horror, namely the climax of the Golden Age arc, where (spoilers) the tortured Griffith, rescued from the king’s dungeon but too injured to ever carry on his rise as a mercenary leader, chooses to sacrifice the entire Band of the Hawk to demons in order to make himself a kind of demon lord. Most of them are torn to pieces, but Casca is raped, first by tentacle monsters and then by Griffith himself while Guts looks on powerlessly. The manga forces us, like Guts, to watch; it is one of the most viscerally upsetting scenes I’ve read in manga, even by contrast to the blood and guts and deaths of beloved characters throughout the rest of the eclipse.

At the same time, there’s a lot of rape or attempted rape that’s just kind of… there, part of the broader texture of violence that fills the series. Our actual and would-be rapists include mercenaries, apostles and at one point monstrous trolls; Casca in particular gets the absolute worst of it, with many attempted rapists showing up both before and after the eclipse. The first time I read Berserk, I felt strongly about such portrayals and couldn’t read much further than the Golden Age arc - now I’ve evidently changed my mind about what’s appropriate to treat in fiction in general.

At this point I think it’s up to each person to decide what they’re comfortable reading and all I can do is just, tell you what you’re in for.

Perhaps it’s worth digging into what role this serves. Berserk is of course deeply concerned with the subject of violence in general. Guts’s defining feature is his connection to violence; he has killed hundreds if not thousands of people and is separated from the rest of the world by the fact he’s attacked nightly by demons. It does a good job of depicting violence as both alluring and repulsive and in many ways, nihilistically treating it as just natural; we’re often reminded that the people slaughtered for Griffith’s dream or because they got on the wrong side of Guts are often just people, other mercenaries, who probably followed their own charismatic leader or just went to war because they had no other way to make a living. Moreover, it is very interested in notions of domination and powerlessness, and this is where the sexual violence fits in. And honestly, these kinds of ero-guro elements seem appropriate for what this story is about.

And yet, the way it treats rape is curiously… limited. It seems even a giant monster completely divorced from humanity will only ever get the tentacle dick out because they see a woman. Casca is often quite awkwardly depicted as ‘the girl one’, with most of her conflicts stemming from that - there’s even a plot point where she goes into battle and can’t fight as effectively because she’s on her period. Often it seems like the only way Miura can think to give a conflict to Casca is by having someone try to rape her. (By contrast, women who appear later in the story like Farnesse and Schierke tend to get very different conflicts - as much as even early Berserk features brilliant writing, I think Miura surely matured while writing it.)

One possible explanation I’ve heard is that Miura’s editors at Young Animal magazine knew that the sexual violence sells, so they would pressure him to put in things like rapist trolls to satisfy that side of the audience. Right now I don’t really have any evidence to confirm this one way or another.

So… all in all, it is what it is I guess. Know what you’re going in for and make your decision appropriately.

Berserk has been adapted to animation three times. The best known one is the TV adaptation by Oriental Light and Magic (OLM), best known for their adaptation of Pokémon(!), which actually began at the same time as their Berserk in 1997. It’s hard to imagine two more completely different franchises. Their adaptation, and in fact subsequent, focused on the Golden Age arc - unlike the manga which introduces the Golden Age as a flashback, it starts the story from the beginning.

This 90s anime series, although inevitably limited by the bounds of TV animation, was very well-loved and was for many people the first introduction of the series. Even with two cours (25 episodes) to play with, it had to cut a little, and due to TV censorship I’m told it ends rather abruptly in the middle of the eclipse sequence.

Notable is the soundtrack by Susumu Hirasawa, who would later become famous as the composer for almost all Satoshi Kon’s films (Animation Night 16, Animation Night 42). It’s got that classic 90s end-of-the-cel-era look, with muted colours and frequently impressively detailed drawings. It’s of the kind of vintage where encoders will be quite particular about preserving film grain or not!

However, two cours of anime is too much for Animation Night, so this is not the version of Berserk we’re going to cover. Instead, we’re going to look at Studio 4°C’s take, a trilogy of movies released 2012-2013.

Here, I may refer you to youtuber SteveM, who made a good retrospective on the trilogy in the context of 4°C’s broader work:

The impetus for this one comes from Lucent Pictures, who approached 4°C after seeing their work on films like Tekkonkinkreet and the Animatrix. Producer and 4°C cofounder Eiko Tanaka was actually unfamiliar with the work at the time; the decision to focus on the Golden Age arc comes from the screenwriter. First came a pilot in 2008, which earned Miura’s approval; the subsequent single movie ended up splitting into three to contain the material, and still cuts a lot compared to the pacing of the TV series.

4°C’s overall approach was to combine cel-shaded CG with traditional animation, an approach which would allow them to take on the enormous battle scenes and complex suits of armour. As SteveM describes, the result is… a bit of a mixed bag, visually speaking. 4°C are definitely one of the best when it comes to merging 2D and 3D, but this time they were applying it to living creatures rather than environments or machines for the first time. The results often looked awkward and uncanny in motion, with the attempt to animate the CG on 2s to mesh better with the 2D frequently ending up with the worst of both worlds. This was improved a lot by the time of the third movie, but still an unfortunate weakness.

Despite this, this is anything but a passionless project; they got in HEMA practitioners to choreograph the fights and went to considerable effort to include historical armour and weapons - perhaps a misguided effort since historical accuracy was never especially the point of Berserk, but definitely a sign of something. And at least going by the reactions of critics, the troubles were largely ironed out by the third movie, which finally got to deliver the Eclipse sequence in its full horrible splendour. In the comments of that video, there are some interesting discussions of what 4°C did better: some people point to the romantic scenes between Guts and Casca, the moment where Guts accidentally kills a child, and the amputation scene in the eclipse arc.

I don’t have an opinion yet! Right now I’m purely a manga reader and haven’t seen any adaptations of Berserk. So I’m looking forward to seeing how all this hangs together in full tonight. Berserk is something that’s impossible to adapt without some sort of compromise, so the strength of an adaptation will be what it chooses to make of the material.

And oh, god, look at the time - that’s about all I have time to write. Thanks for bearing with me. We’ll be starting the Berserk movie trilogy very shortly, at our usual spot, twitch.tv/canmom - hope you can join me, I’ve been looking forward to this a while!

Comments