originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/677763...

Hello, friends. Been a tough week, apologies Gundam trilogy night kind of collapsed on itself without even showing the third film, but Animation Night is one of the only constants I have so it’s going to keep going.

Usually the tradition is that on numbers ending in -5, I tell a story about the history of a particular animation technique. However, we have actually covered most of the major ones!

So instead, let’s have a look at someone who was very influential on a particular style of animation - the renowned Osamu Dezaki (出﨑 統)…

You hear anything about Dezaki, it’s that he’s wildly influential. While a different Osamu may have established TV anime to begin with, Dezaki gave it a new identity. You’ll often see his name pop up in writing about other anime auteurs, such as Hiroyuki Imaishi (whose works are full of overt allusions to Dezaki, like the end cards in KLK or Kamina’s entire death scene) or Kunihiko Ikuhara. Indeed, he was among the co-founders of Madhouse, and directed most of their work through the 70s.

But let’s try and dig a little deeper…

What are these characteristic Dezaki-isms, apart from those heavily stylised still frames? Perhaps his theatrical approach to staging, or the detailed end cards known as ‘postcard memories’ he popularised with Ashita no Joe. I haven’t been able to find a really good source on his life specifically, but I do have Matteo Watzky’s history of Tokyo Movie Shinsha, and that’s perhaps more useful for the broader framing. This led me to an interview here where Dezaki talked about his own early years.

Dezaki got his start back in the old days of Tezuka’s studio Mushi Productions, one of the first wave of artists - many with no experience in animation - drawn by Tezuka’s charismatic repuation. Watzky says he actually got his start as a series director on a TMS show, The Big X, a robot show in the vein of Tetsujin 28-go. Before long, with the completion of Astro Boy, he would advance from mostly doing key animation to mostly doing direction, and leave Mushi Pro to go freelance.

At this time, there was at this time a division between two major schools of animators - the limited animation school of Mushi Pro and descendents, for whom the quality of a single static illustration was a higher priority than motion, and the Toei Douga school whose ideal was closer to ‘full animation’, and frequently disdained the former group. Let me quote Dezaki’s own words on this, from the above interview:

Dezaki: Mushi Pro was comprised of rental manga artists who had trouble making ends meet once TV was widespread and the rental manga boom had dried up. Lots of those people could illustrate well. The Tōei Dōga folks were different. They were people who went into the industry with the explicit purpose of becoming animators. This was the fundamental difference between the styles of these two groups. The Tōei folks prided themselves on being people who created feature length animated films, whereas the Mushi Pro folks, as you’re well aware, kicked off the trend of limited animation with Astro Boy. In limited animation, due to the severe limitations in budget and framerate, it was focused on expressing the qualities of the illustrations themselves. The quality of those illustrations is what crafted the scenes.

Watzky notes a technical element in this story. Originally, drawings would have to be traced onto animation cels, usually by a tracing department that was majority women. However, the invention of the Xerox machine in the 60s - which famously allowed Disney to create 1001 Dalmations - shook up this structure, unfortunately eliminating the tracing department. It particularly allowed illustrators of the Mushi-Pro school to draw extremely complex and detailed illustrations, opening the door to Dezaki’s ‘picture memories’.

What narrative possibilities did these detailed illustrations, with their rough pencil lines, create? At this time, boys’ manga was seeing a movement called ‘gekiga’ featuring gritty stories and heavily hatched, more realistic drawings, and meanwhile shōjo manga was being transformed by artists like the Year 24 Group. Many gekiga stories were about sports, in the wake of the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, and in 1968, this movement reached anime with baseball series Star of the Giants at TMS, on which Osamu Dezaki’s older brother Satoshi was a storyboarder. You can read more about that here; for our purposes, let’s just note that as the environment that Osamu would soon establish himself.

Dezaki’s star really rose with Ashita no Joe, working as a freelance director at Mushi Productions, one of the studio’s final works. (He also worked on their last gasp ‘animerama’ trilogy, including Belladonna of Sadness (Animation Night 69), although ‘only’ as a key animator.) This was a sports manga adaptation, very much in the vein of Star of the Giants, but this time focusing on boxing rather than baseball; like many gekiga works, it has a heavy overtone of drama and realism: the young protagonist is poor and soon ends up in prison, where he gets his start as a boxer.

The series, both in manga and anime form, was a massive hit, with some surprising impacts. The death of a major character led fans to stage a funeral:

When the fans of the series saw the death of Rikiishi, there was a special funeral for him. In March 1970, about 700 people packed the streets dressed in black, wearing black armbands and ribbons with flowers and incense, participated in the funeral. The event was called for by poet Shūji Terayama. The service was conducted in a full scale boxing ring watched over by a Buddhist priest.[1]

Even wilder, its hero became a working class icon, and even inspired members of the Japanese Red Army Faction to shout ‘We are Ashita no Joe!’ during the Yodogo Hijacking Incident.

Approximately 20 minutes after takeoff, a young man by the name of Takamaro Tamiya got up from his seat and drew a katana shouting “We are Ashita no Joe!”[3], stating his intent to hijack the plane, and instructed the other hijackers to draw their weapons.

The hijackers ultimately managed to direct the plane to North Korea, after several exchanges of hostages, where they defected and were offered asylum.

Not so long after this, Mushi Pro collapsed under the weight of debt and folded. Dezaki, along with some other former Mushi-Pro artists including Rintaro and Yoshiaki Kawajiri, founded a new studio, still in the TMS orbit: this was Madhouse, and would go on to become one of the most storied studios of the 80s and 90s.

Dezaki became the studio’s main director throughout the 70s, a presence so overbearing that some of the others would actually leave the studio to learn to direct in their own way. His first project there was tennis series Aim for the Ace! (エースをねらえ! Ēsu o Nerae!), adapting a manga by shōjo artist Sumika Yamamoto. Over this period, he developed his iconic stylings: highly abstract backgrounds, compositing elements to create meaningful narrative relations rather than construct a realistic 3D scenes, lens flares and other lighting effects, and camera techniques in the multiplane like depth of field and false colours.

Aim for the Ace! ultimately set the template for the classic Gainax OVA Gunbuster (Animation Night 29), which took elements of its storytelling and projected them into a space opera story.

At Madhouse, Dezaki would work simultaneously on a variety of projects. These would include The Adventures of Gamban about a group of sailor mice which took on some of the gekiga stylings of Ashita no Joe, discussed extensively in that interview. Then there was Nobody’s Child (Ie no Ko) adapting a French novel about an orphan travelling with a group of players. Watzky writes of the latter:

First, it was Dezaki’s first experimentations with 3D animation – or what was called 3D at the time. This claim by the studio’s producers was probably because of the show’s strong designs, animation, and especially its innovative use of the multiplane camera to create a dynamic sense of depth. TMS would go further in 1980, as they used a certain stereoscopic process during the projection of the show’s compilation movie, which appears to have made it the first real 3D anime [Clements and McCarthy, 2015, p.584]. Moreover, Remi appears to clearly have been TMS’ attempt to renew itself and rival Nippon Animation’s World Masterpiece Theater : it followed the exact same yearly format and adapted a classic of children’s literature – in that sense, it might be considered as Dezaki’s attempt to imitate and overcome Takahata’s realism that was developing at the same time in the series.

Another notable series from this period was the Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi, a collection of ten minute adaptations of folk tales from around the world, directly inspired by an earlier Japanese-focused series Manga Nippon Mukashi Banashi. (Many of the latter have been uploaded by someone called Toadette on her channel.) Both MSMB and MNMB are notable for their much more experimental elements, setting up for the auteur-driven madhouse of the 80s.

Dezaki’s other big direction from this period was, from episode 19 onwards, the adaptation of renowned proto-yuri shōjo manga The Rose of Versailles (a manga highly influential on the Takarazuka Revue, which I discussed briefly a couple of weeks ago on Animation Night 92). This last would also be incredibly influential on Ikuhara’s Utena, not just with its images of women in French courtly uniforms, duelling swords, roses and thorns, but also in the directing style.

I don’t have a detailed account of the production of Rose, but I get the impression that Dezaki worked closely with the mangaka Riyoko Ikeda; also frequently mentioned in the credits is animation director and character designer Shingo Araki (not to be confused with the other Araki!). When Dezaki stepped in as director, it apparently created a notable tonal break in the series, although I’m only going to be able to sample it tonight.

This period also covers Dezaki’s work on Lupin III, but I’m going to save that for a future Animation Night.

Dezaki actually went on to leave Madhouse in 1980, in pursuit of more focused work on series like Ashita no Joe 2, creating a new studio called Annapuru, ending that particular era for the studio. That takes us on to… Space Adventure Cobra, a film and then series that has been compared to such works as Barbarella and Zardoz, and elsewhere termed ‘psychedelic’, so I’m fascinated to see what that means in practice.

This is I think where I’m going to have to stop my story, for the sake of time as much as anything. Tonight’s bill is gonna be…

- a sample from Ashita no Joe and Rose of Versailles

- the Aim for the Ace! compilation film, which is actually mostly reanimated footage

- and Space Adventure Cobra!

We’ll be starting very shortly at our usual place, twitch.tv/canmom, and probably continuing until quite late. Hope to see you there!

Having now watched the above things!

Ashita no Joe was a blast, holds up really quite well! Genuinely charming sense of humour, it’s got those simple but compelling characters of that sort of period of anime, Joe is a very enjoyable MC, arrogant kid less interested in being a champion boxer in the first couple of episodes as raising havoc with the local yakuza. Definitely gonna watch the rest of this!

The Aim for the Ace! compilation film was a very fascinating one. I thought it would be a fairly straightforward story about doing your best and winning at sports, and to some extent it is, but the shōjo trappings were much more overt than I expected, and the narrative honestly took a darker turn. The emotionally distant coach in this one is an aging former athlete who essentially singles out a fairly average girl who reminds him of his mother to a viciously intense training regimen for reasons that are entirely his, and most of the film actually sees her failing at tennis, with nobody able to explain the coach’s interest in her. The way he treats her is very uncomfortable - not just making unreasonable demands for training but even confiscating her belongings - and it comes across as a very dark film. Beautifully shot - you can really see Dezaki the director here, with a lot of very artfully composed shots.

The two episodes of the Rose of Versailles anime we saw were great - all that shōjo decadence and melodrama perfectly at home in Versailles. We watched episode 1, and then Dezaki’s first episode 19, and you can definitely see it’s him with the “postcard memory” static shots and such - it’s also an immensely dark episode with a young girl killing herself to escape an arranged marriage to a much older man. I am really looking forward to seeing the rest of this, the mangaka’s leftist background is evident in how it’s approached and I can see why it’s such a classic.

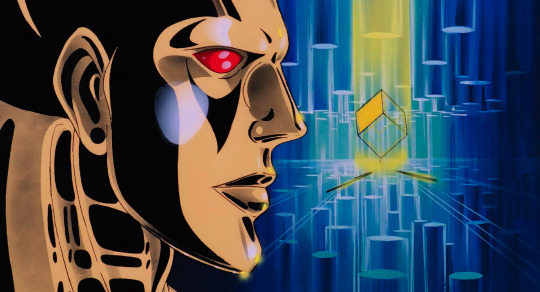

And then, Space Adventure Cobra, holy shit! That was honestly the most Humanoides thing I’ve ever seen that’s not actually French; so many of its stylings seem to draw overtly on elements of French comics, from the derangedly horny grand space opera to the particular ways of drawing very structured faces for the villain. The Barbarella comparison seems very apt. It’s just packed full of beautiful, inventive setpieces and designs for machines, aliens, locations… gorgeous 80s anime colours and animation styles as well. Really outstanding film and I’m kind of surprised I never heard more about it. Look, just check out these stills…

After this, I can really see why Dezaki was such a big deal. Look forward to when we return to him to check out his Lupins!

Comments