originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/703739...

Good afternoon everyone! Welcome back to my odd little… column I guess, in which I infodump about animated films (or topics only tangentially related to animated films, like the history of the samurai) and attempt to, in some sense, curate a big collection of all the great animation in the world that I can find? That’s kind of what this ended up being, huh.

Writing about animation is tricky. After avoiding some of the most obvious clichés - it’s so smooth! - you’re left with some slightly less cliché phrases like ‘strong key poses’, ‘graphical’, ‘sense of form’, ‘energetic’, ‘weighty’ ‘strong character acting’… or maybe you throw open your mental dictionary of production terminology and praise the ‘boards’ and ‘LO’ and ‘sakkan work’ and ‘genga’, which has the great advantage of making you sound like an industry insider even if you’ve never worked a day in animation (*cough*).

To get further you need to get very specific, and start pausing on specific frames and drawing bright red over things, and pull out your deck of animation principles and artist words - timing, spacing, arcs, line of action. This is the specialty of the Twitter account Frame by Frame. A useful type of analysis but also one that is very easy to parody…

‘course you might say this is less a parody and more a perfectly legit “animation” analysis with an unusual subject.

But the real reason for all of this is that animation is something you feel more than process in words. When you create an animation, you can plan it out carefully with keys and breakdowns and arcs and timing charts (a skill that was all the more necessary when you couldn’t hit a ‘play’ button in your software) and apply concepts you might know about like ‘hand accents’ and ‘overshoot and settle’ and so forth, but even with that you are going to spend a pretty long time flipping between drawings, erasing and redrawing bits, and shifting the timing to and fro until it just looks right. And then when you watch an animation, it evokes a feeling that can’t just be broken down into all those applications of technique. And describing feelings in words is its own entire art form…

Anyway, that’s a roundabout way of… partly self-reflection, because for a series of essays about animation I don’t do a ton of actual animation analysis so much as biographising, but also to say, today’s subject is a pretty tricky one to approach!

Tonight the plan is to look into the Zagreb School of Animation - not a literal institution but a (loosely defined) artistic tradition that began in the 50s in what was then the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, centered around (you’ll be shocked to learn) the city of Zagreb, capital of Croatia.

The occasion for this is the appearance of the Zagreb Film channel on Youtube, which has been uploading clean, HD releases of dozens of old Czech films. But it’s also heavily indebted to the blog Animation Obsessive, who wrote about the Zagreb Film channel, and before that, a great deal about them and specific films made by artists associated with the Zagreb School.

OK, these guys are from Zagreb, but what makes them a big deal? We can say their influence is a unique graphical style influenced by the once-renowned UPA in America, all an overt and conscious break away from the ‘full animation’ of Disney. We could talk about their influence in Eastern European animation and worldwide. We can perhaps quote a certain manifesto, from an art show in 1968…

Animation is an animated film.

A protest against the stationary condition.

Animation transporting movement of nature directly cannot be creative animation.

Animation is a technical process in which the final result must always be creative.

To animate: to give life and soul to a design, not through the copying but through the transformation of reality.

But that doesn’t actually tell you very much, and also that’s where it gets trickier, because the Zagreb School - especially in their earlier years - were crazy varied in their output. As AniObsessive put it…

The Zagreb School is a tricky thing to pin down — scholar Ronald Holloway said it best when he called it “a loosely fitting group of artists in open competition with each other.” Many of its key figures were art-school graduates. Even more had a background at Kerempuh, something like Yugoslavia’s answer to MAD Magazine.

It was never just one thing. Zagreb School cartoons are wild and anarchic until they’re sad and serious. They’re cartoony and geometric until they’re loose and painterly. It’s less of a style and more of a “protest,” per a manifesto signed by some of the key members.

So to get more concrete, we’ll have to narrow our scope to particular artists and films. I’m not going to be able to do the Zagreb School anything like justice - there have been massive books written about them, and even when AniObsessive boil it down, that gives several long articles - so take this post more as a signpost, to explore further if you’re curious…

Here is Kod fotografa (At the Photographer’s) by Vatroslav Mimica, with lead animation by Vladimir Jutriša. I’m leading with this one because AniObsesive have written an extensive breakdown of the animation style, which is a great read. But here let me put in a little background…

Traditional animation is usually divided into two broad strands. To start with, there is the famous ‘full animation’ pursued by Disney, spreading to Warner and later carried on by Disney offshoots like Don Bluth and Dreamworks. It’s a style which really came into its own in 1937, with The Old Mill (1937) and Snow White. Inspired by studies of live action film using the rotoscope (see: Animation Night 65), ‘full animation’ pursues what Disney called ‘the illusion of life’, when the drawings cease to seem like drawings and appear as a living, breathing character.

To this end, ‘full animaton’ places drawings on 2s and 1s (12 or 24fps) - mostly on 2s, speeding up to 1s for rapid actions, and applies a body of techniques summarised by Disney’s ‘Twelve Principles of Animation’ to create a sense of continuous motion: arcs, overlapping action, overshoot and settle, lots of dangling bits to shake and wobble. A huge emphasis is placed on acting, with the animator conceived of as an actor inhabiting that character and lending them unique mannerisms, drawing initially on the ‘broad’ acting of vaudeville performers but later splintering into more reserved styles suitable for more dramatic stories.

‘Full animation’ traditionally avoids certain techniques that will break the ‘illusion’. It will rarely use hold frames, or shots that are just multiplane effects. The extreme of full animation is the work of Richard Williams (Animation Night 119).

Then there is ‘limited animation’. This is mostly associated with TV animation, both in the States and in Japan, where the need to make a lot more animation in a much shorter time necessitated production shortcuts. These include

- animating at a reduced framerate anime will usually animate on 3s i.e. 8fps, or even 4s i.e. 6fps, and drop to 2s for fast action

- hold frames the same drawing stays on screen for a long time

- partial holds when most of a drawing stays still, but a small part is varied, e.g. a character’s mouth and maybe jaw moves to indicate speech while the rest of their face stays still

- moving holds a single drawing is moved across the screen without changing. can be used to, for example, make a very cheap walking shot by shooting a character from the shoulders up and moving them up and down while scrolling the background

- bank shots repeated footage that is reused, sometimes every episode - e.g. henshin (transformation) sequences in old-school magical girl and super robot anime

- multiplane effects/animetism when animation consists of sliding ‘book’ layers passing over each other, without trying to create an appearance of 3D space

- loops particularly for repetitive actions like walking, but also sometimes for background animation - a handful of frames can be cycled repeatedly

As anime envolved, animators like Yoshinori Kanada (AN 62) and directors like Osamu Dezaki (AN 95) appeared who found ways to make animation that turned these limitations into strengths. Anime started to emphasise the storyboard and layout, with increasingly elaborate camera moves and a very cinematic approach to the animated ‘camera’. And viewers got used to animation on mixed 2s and 3s, and even started to come to recognise the special value of its ‘snappy’ feel - which is incidentally part of the reason for animators’ loathing for AI interpolators.

It’s not strictly that one is the ‘Japanese style’ and one is the ‘American style’ mind you. Indeed, ‘full animation’ has mostly been practiced in just a handful of studios, mostly in America, and almost exclusively in films, because it is kind of insanely expensive.

Then we come to the slightly more obscure terms for ‘hybrid’ styles, such as the ‘full limited’ of Mitsuo Iso - although this is subject to many misconceptions as @why-animation noted for this translated interview. But to briefly summarise, ‘full limited’ refers to mixing the techniques of full animation - constant movement, strong sense of weight and overlapping motion - with the reduced framerates of anime (typically on 3s). The iconic example is Iso’s animation of Asuka fighting the Mass Production Evangelions in End of Evangelion.

I mention this because I’m about to talk about a very different sort of ‘full limited’. The ‘reduced animation’ - a term coined at UPA - practiced by the Zagreb School is a form of ‘limited animation’… yet one that paradoxically often involved extended sequences on 1s, as you can also see in this brief ad…

The way this is still ‘limited’ is that these ‘smooth’ sequences are one of two extremes. Characters slide with uncanny smoothness from pose to pose… or they remain perfectly still, moving our attention around the frame. As AniObsessive note, the spacing is very even, where conventional animation wisdom would say you should use a slow-in or slow-out, overshoot and settle. It’s consciously extremely unnatural, in an arresting way.

So returning to At the Photographer’s… (link, again) - this film builds on that into a fascinating string of visual gags, morphing pespective, playing with shapes… it feels in some ways like Flash animation, way ahead of its time. The film’s soundtrack is entirely musical, timed with the animation in a way resembling the ‘Mickey Mousing’ of Disney, but here used to create an uncanny distancing effect. The photographer struggles to get the boy to create a proper smile, an expression represented by hyperdistorted photo collages, a technique also used (along with painted elements) in the background.

I won’t try to itemise every gag, but I think it is cute how the kid’s mouth floats around his face like a little fish.

Czech animators at the time of this film, and honestly pretty much throughout the existence of the ‘school’, were working with truly limited resources. Pavao Štalter, director, background artist and lead animator of The Masque of the Red Death (1969) once described it…

All of our cameras are made from aircraft scrap from landfills. We are madmen who work with abnormal effort. Instead of making a film in three months, it takes us a year. Everything is done by hand. … Here in my little room in the studio, it is 45 degrees Celsius in the summer, and we work ten hours a day! I really don’t know how long we can say, “Tomorrow will be better!”

Masque shows a very different face of the Zagreb School, with the gloomy, textured, bleak world of expressionist paintings. Its animation is a mix of cutouts and traditional animation in paint. Its process was discovered experimentally, Poe’s story is presented without dialogue, though there are some really choice screams and there is a song with lyrics. But mostly it’s an incredible atmosphere piece.

Masque, writes AniObsessive, was also unusual in its funding: while Zagreb Film received funding from Tito’s government, in an unusually hands-off arrangement, it didn’t go very far. For Masque, a large part of the money instead came from the American company McGraw-Hill, primarily an educational publisher, a serendipitous connection made by a display of the film’s storyboards at MoMA. You can read more about its story here.

So that’s two points in the constellation - but where did this distinctive school come from? Well, we need to take our story over from Croatia to Czechoslovakia, on the far side of Hungary. (Hungarian animation is also a story, but one for another night.) That takes us back to the 1940s, with the early films of Jiří Trnka, covered here by AniObsessive.

At this time, Czech animation under studio AFIT had just been freed from Nazi control with the end of the war. Their managers in this period were outright caricaturish, like, if you wanted to imagine a Nazi directing a cartoon studio it would probably go something like this…

The owner was an Austrian architect with ambitions to become something between a European Disney and Richard Wagner. He liked to do operas in cartoon. Unfortunately, he had a very limited imagination. Everything we drew was rotoscoped from poorly-acting opera singers. The results were awful. At the same time, we were learning basic animation by secretly studying a few prints of Disney films.

AFIT were eager to get a Czech illustrator to get things back on track, so they turned to a local comic book artist in his 30s, Trnka. And Trnka, despite having zero animation experience, turned out to be the perfect man for the job, pre-empting what would later be known as the ‘UPA style’ of flat graphical shapes and limited animation.

That brings us to The Gift, a charming metafictional satire about filmmaking, and although initially landing to a poor reception, it spread around the world - actually influencing that same UPA. Naturally, it made the short hop to Yugoslavia…

it was a pillar for animators there. “The Gift was the key film in the formation of the Zagreb School of Animation,” per Holloway. The young animators studied it closely, intrigued by its “national character.” Just as Trnka had created a so-called Czech school of animation, they would create their own.

But even more influential on their style was Trnka’s next film, Springman and the SS, which pits folk hero ‘Springman’, a chimney sweep with spring heels, against the recent occupiers. The film’s wildly inventive animation, with its ‘long weaselly tube’ of a collaborator and other abstract designs, apparently really lit a fire under the Yugoslavian animators.

Yugoslavia pilfered from this film relentlessly, and with great results. The tall character in Dušan Vukotić’s Piccolo looks suspiciously like the collaborator. Even Springman’s photo-collage backgrounds turn up in Zagreb’s The Inspector Returns Home.

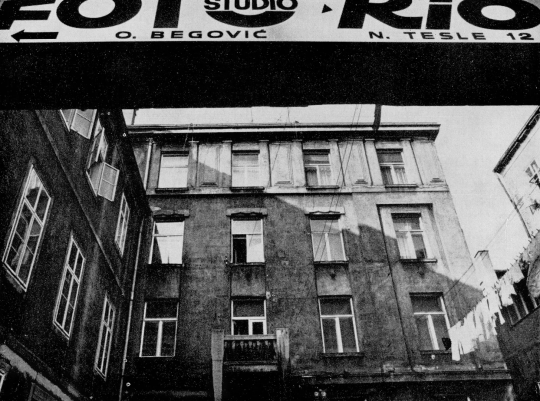

Over in Yugoslavia, the story begins with The Big Meeting (Veliki Miting, 1951), some time before the government art funding even began. The “Zagreb school” was never concentrated around just one studio.The Big Meeting was succeeded by the founding of Duga Studio in an effort to make better cartoons, but it imploded fairly rapidly under the weight of trying to make animation in the Disney/Fleischer style with its demanding drawing counts. A handful of its animators gathered in a small apartment on Nikola Tesla Street, desperate to keep the art alive.

The apartment studio was stacked with talent. There were designers Aleksandar Marks and Boris Kolar, animator Vladimir Jutriša and more. Most crucial of them all was the main director and writer, Dušan Vukotić, who’d been a huge force at Duga Film. He would go on to win an Oscar for his cartoon Ersatz in 1962.

Their early works were thus mostly ads - and this is where they pioneered the ‘reduced animation’ style discussed above.

In 1956, this group of animators found itself absorbed into the larger Zagreb Film as a specialist animation division, and it’s here that the ‘Zagreb School’ of animation really took off. Not that they didn’t continue to face some honestly kind of absurd obstacles. In 1958, Vatroslav Mimica smuggled his film Alone to the Cannes film festival in France, against the orders of the government.

You see [the slower, more meditative pace of Mimica’s films] in Alone (1958), a Zagreb masterpiece. Amid the modern graphics and indescribable soundtrack, it’s a beautiful film — in its own way. It’s a parable about a man who gets sick of his fellow humans, and the office co-worker whose love he rejects and ignores. Then he has a terrible dream where he’s truly, fully alone, at last. When he wakes up, he realizes that he has to accept the love that the world offers him.

Luckily for him, his film was a big success - the French coined the term ‘Zagreb School’ for this exciting new movement.

And here’s another fun anecdote, which I can’t paraphrase…

There was strife, too. All the awards inspired Vlado Kristl to return to Yugoslavia and join Zagreb Film. He pushed the team’s design sense forward, but battled with them every step of the way. (Holloway called him a “mad genius.”) When someone suggested a change to Kristl’s landmark Don Quixote, he threw an inkwell at them. By the early ‘60s, he’d made a film attacking Tito — and was forced to flee Yugoslavia.

In 1962, Dušan Vukotić saw his film Ersatz nominated for an Oscar - but no film by a non-American director had ever been recognised with a win at the award for animation (at the time, ‘Best Short Subject - Cartoons’), so he didn’t bother to go. To the surprise of pretty much everyone, Ersatz (Surogat) took the award. His friends gave him a box of Oskar-brand detergent while they waited for the award to make its way over. Here’s the film:

It depicts a beachgoer with a variety of inflatable objects… honestly I don’t know how else to describe it but harassing the hell out of an inflatable woman, and failing to win her around through a series of visual gags. I’ll admit, I can see why AniObsessive saw it as not being Vukotić’s best film, but it is the one that made history by impressing the Americans. Like most of the other films we’ve seen, it’s wordless, with just music; its character designs have been abstracted the point of being geometric figures connected by lines, which really does underline just how much you can show with the most abstract shapes.

For a better work of Vukotić, they instead would suggest we go with Cow on the Moon (1959), which does some classic ‘playing with the medium of film’ stuff, and which our guides compare to Dexter’s Labatory.

And oh, is that five videos? That’s five videos again.

There’s many more films we could yet cover, but I’d like to start in about 25 minutes, so for now I will say if you want to get a preview of our programme tonight, read AniObsessive’s (non-paywalled!) article here. Some sound especially enticing…

Maybe even more reckless is Kostelac’s Ring (1959), a film whose look needs to be seen to be believed. Far from using “limited animation on ones,” lead animator Leo Fabiani drew quite possibly the most chaotic motion ever put to mid-century graphics. His disregard for forms, volumes and model sheets can only be compared to Jim Tyer. This is a rare cartoon, new to us, and we can’t stop thinking about it.

So, while I hope I’ve conveyed the main points of AniObsessive’s wonderful coverage of the Zagreb School, please don’t take this as anything more than a skim over the surface. Read their articles (they are so worth the sub), or if you’re feeling really eager, dig into books - the multi-volume The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films or Z is for Zagreb.

Soviet-bloc animation has been a bit of a neglected side of the world on Animation Night, which is a shame because there’s a ton of really inventive stuff - but unlike with anime, it’s hard to come by info in English without shelling out a lot of money for academic books (and knowing what books to get in the first place). I’m eternally grateful for AniObsessive helping to improve the situation.

Animation Night 136 will go live at twitch.tv/canmom on the hour (9pm UK time), about 15 minutes from now, and commence films about 20 minutes after that! We’ll be running all over AniObsessive’s picks from the Zagreb Film archive - you should be able to jump in pretty much whenever. Hope to see you there!

Comments