originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/677111...

Apologies for the very late start today. I’ve not been at all functional. I understand that most eyes are on Ukraine right now. Nevertheless, it is important to me to keep up the streak of Animation Nights, so an Animation Night there shall be.

Since it’s so late, and I’m not in the best sorts, I’m going to lean on a previous writeup; we’ll be looking back at the misty origins of the vast Gundam franchise, and a curious set of historical events.

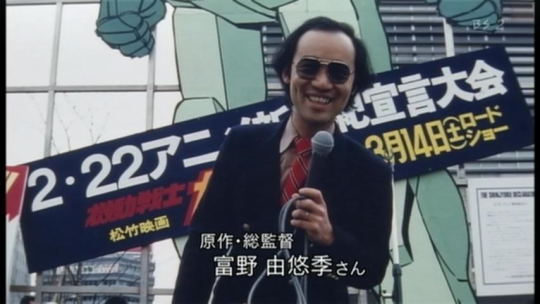

Today is 24th of February, two days off from February 22. Back in 1981, February 22 was the premiere of the film adaptation of Mobile Suit Gundam; at first an unsuccessful television show that tried to inject elements of ‘realist’ sci-fi war drama, which became a cultural phenomenon on the back of ‘gunpla’ model kits, and then, a symbol of the changing audience of animation in Japan - something which Tomino would claim as a ‘New Anime Century’ (anime shinseiki sengen) at the occasion of the film’s premiere.

Normally I would launch right into the history, but I feel like the context means I ought to say at least something about how this all connects to our time. Because a war has just considerably escalated in Ukraine, joining the ongoing wars in e.g. Syria and Yemen, as various imperialisms vie for dominance and various groups of people of myriad ideologies cast in with this or that faction that might protect them, or get caught in the fighting of others, like the Saudi naval blockade and resulting famine. “What the hell you even do” is a question we continually face, especially when we are so powerless - something acutely experienced by e.g. the Ukrainian anarchists interviewed here, for whom the choices not ‘what to tweet’ but whether to pick up weapons, and if so, how to avoid their tiny movement getting subsumed into a nationalist project.

Understanding a war at the time it’s taking place is very difficult; in the years following, it falls to artists of various kinds to end up defining the social meaning of that war, and the whole sorry spectacle of war in general. Is that a good thing? Who the fuck knows. But it happens, regardless.

So, for example, thanks to novels and memoirs like All Quiet on the Western Front and Poilu, famous poems, and various histories (an art form itself) constructed by sifting through the records and propaganda, the gigantic act of human sacrifice that broke the old imperialist system and opened the ‘bloody twentieth century’ can be turned into a story that we can at least pretend we comprehend in some way as ‘World War I’. (For good or ill! The Italian futurists and, later, Nazi propagandists turned their artistic efforts towards telling a story to further or repeating that war. And of course, during the war itself, all sides called on their artists and reporters to tell stories that would maintain the supply of bodies and shells to combine alchemically into ‘political power’ and corpses.)

In the decades after whatever temporary peace is found, the art ends up talking not about our direct experience of living through a war (an experience that is traumatic even far from the actual fighting), but the images of it we receive in art. The Nazis, for example go from actual people who you or your audience may have physically fought or lived under or fled, whose genocides were only recently exposed, to cartoon villains or even edgy sex symbols. The survivors gradually die and romantic narratives take over from people to whom that war was a story. And yet, the experience of these later generations living in the shadow of all the millions of empty deaths is still something that will - inevitably! - be expressed in art.

(this is from 08th MS Team so the animation is a bit more modern than what we’ll see today - I don’t really have time to scour the gif searcher for OG gundam clips!)

So, Gundam. Famously, Tomino is an ‘anti-war’ director. But whether an ‘anti-war’ film is even possible has often been called into question. Certainly, you can present images of senseless death and suffering - but the cult of the soldier loves the struggles borne by its ‘heroes’ for the sake of the nation. (The logic of sacrifice transfers the value of the thing sacrificed; kill a prize cow for a god, and you are declaring that to you, such food and wealth is less important than the god. Kill a million soldiers in ‘service’ of a nation, and the psychic power of the nation is strengthened, not weakened, by the value of a million human lives.)

It is easy to say “war may be an awful thing, but this time, we must fight” - and to recognise the logic of violent domination and coercion that doesn’t care for principle. And so, those who wish to start or sustain a war have long, long ago learned that they need to make a plausible-enough case that it is ‘justified’ to maintain their supply of bodies, and have developed very sophisticated ways of telling that story.

Mecha anime, and Gundam in particular, inherits a curious relation to war in general and Japanese history in particular (their failed imperial ambitions and the aftermath of near complete destruction by war, their relationship to the USA in the Cold War, and the question of the restrictions placed on the JSDF, much to the resentment of far-right nationalists).

It depends, fundamentally, on lavishly elaborate depictions of military equipment - before it narrowed to ‘giant humanoid robots’, the term ‘mecha’ simply meant machinery in general, and the visual language of giant robots (especially in Gundam’s ‘real robot’ subgenre) takes a lot of cues from jets and tanks and other such machines. (Last time around, we talked about how the first ‘super robot’ manga, Tetsujin 28-go, imagines a secret WWII weapon in the hands of a child.) Mecha have many meanings, but an inarguably important one is that we are captivated by the image of precisely engineered killing machines; for much the same reason, people adore guns even if they have no intention of killing anybody with them. I don’t think this enables war, inherently - it is a reality of our experience of a violent world that is being reflected truthfully in our art.

And yet, for all that, Tomino wished to tell specifically a tragic story about war; calling attention to the humanity of the enemies, and filling his story with senseless death and grief proper to the subject matter, which was a significant break. How strongly and coherently this theme has been expressed and developed varied through the franchise, which was primarily an instrument to move gunpla models and faced many constraints, but it’s a stance he held fast to pretty much throughout. This productive contradiction has fuelled several subsequent decades of robot anime; in the 90s, Anno’s ‘New Gospel’ of Evangelion would take mecha into a much more psychological direction, but it’s always been in part about war.

And how animation should treat the matter of war (as a subset of film in general) was at the time becoming a significant subject of contention. A year after Gundam‘s film premiere would follow the conflict over the film Future War 198X in which anti-war, Soviet-sympathetic trade unionists vehemently protested what they saw as a warmongering film.

To say more is really more than I have time to talk about tonight; let’s press on to the event in question that frames tonight’s screening: the 1981 release of the Gundam theatrical trilogy and the ‘New Anime Century’. (I talked about Tomino’s career leading up to Gundam last time so go back there for that!)

As this page recounts, the original Gundam TV anime was cancelled, but the series became increasingly popular off the strength of gunpla kits, eventually resulting in a recut of the series into three theatrical films with a great deal of ceremony. The turnout on the day was unexpectedly huge (in part due to the temptation of 10,000 free Gundam posters), and Tomino became afraid that a riot might break out:

By the morning of the 22nd February, there were 2,000 fans at the east exit to Shinjuku station. Tomino wryly observed that a TV director’s life was often lived hand-to-mouth, worrying about little more than the next meal, but here, outside a cinema for one of anime’s first big grown-up movie events, we were seeing the true power of television – its ability to attract an exponentially larger number of viewers. TV people had always been excluded from the movie world – now, suddenly, he saw that they had taken it over.

The posters were gone by 10am. By midday, Tomino estimated the numbers were pushing 15,000, which threatened to turn the event into a riot. Ever since the Anpo Protests over the controversial US-Japan Security Treaty (an event later referenced in the opening unrest of Akira), “public demonstrations” had been illegal around Shinjuku station. Enough Gundam fans had now gathered to risk attracting police attention, and Tomino fretted that an injury in the crowd could attract exactly the wrong kind of media attention. His “new anime century” risked dying before it could even begin, with future events shut down as too dangerous.

So, Tomino made an address to the crowd, like a politician speaking at a rally, with little preparation. His statement was… a curious and still rather boastful one:

“Sorry, but you are dummies,” he shouted, presumably in reference to the number of bodies needed to create a noticeable crowd. But then again, you never knew with Tomino. “We gathered you here to make a statement, to make all the grown-ups wonder what so many young people want to say. And in fact, the statement we really want to make is not about Gundam at all! But Gundam is the name that has gathered you youngsters here today. We need the grown-ups to wonder what this Gundam is all about. We need them to understand what young, modern people, teenagers, are seriously thinking about, and grasp that by seeing Gundam for themselves, even once.”

His awkward address, and official declaration of the ‘New Century’, would be repeated by two younger anime workers:

Tomino spoke from the stage, but doubted anyone heard him. At 40 years of age, he already belonged to a different generation. Ultimately, the proclamation’s official delivery was read out by “the kids” themselves, two young students, who were both already intimately involved in Tomino’s new era of anime: Mamoru Nagano, the future creator of Five Star Stories, and Maria Kawamura, already a voice actress in several Tomino productions, fated to become the iconic Jung Freud of Gunbuster.

Both in cosplay at the time, the two would eventually marry.

Much later, this event would be narrativised as ‘the day anime changed’ - though this seems like far too neat a narrative and many of the elements popularised by Gundam had been in the works throughout the 70s. Still, it did correspond to a turning point: the 80s soon saw the rise of the OVA market and rapid transformation of animation from purely a children’s medium to one capable of attempting more challenging stories - or serving the very specific tastes of adult otaku. Anime directly addressing war would become increasingly emotionally sophisticated - subsequently we would see films like Barefoot Gen (Animation Night 26), Grave of the Fireflies and In This Corner of the World as the realist movement developed. It would be absurd to ascribe all this to the influence of Gundam (as much as it would surely flatter Tomino) but the three Gundam films do stand at a pretty important point in that big historical flow.

Comments