originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/678399...

Hello friends! Happy thursday! This time I write to you from (somewhat) sunny Egham, proud home of the Magna Carta, a power struggle between feudal nobility that would later be mythologised as the first constitution, rule of law etc. etc. - something that would prove a very effective technology for social control in the future.

Tonight, though, our animation studio comes from the States! Actually it was the Americans who built most of the little monuments I saw today, lots of neoclassical architecture in evidence. We’re going to visit… Laika.

I suspect people know of Laika already. The dog who was put on a rocket and sent to die alone in space, of course - but also the American animation studio who borrowed the dog’s name that became known since 2009′s Coraline for their charming, comfortably dark stop motion films…

So what’s the story here? Like a lot of stories about the American entertainment industry, a lot of the story is about money and the weird foibles of the rich. But we have a winding path to get there, including the very dawn of clay animation.

Our story begins (if we can perhaps arbitrarily pick a beginning) in the early 1970s with the meeting of Will Vinton, who had just finished his architecture degree during which he’d experimented with making documentary films about student protests and the counterculture movement, and Bob Gardiner, a stop motion animator (check out Animation Night 50!!) who was among the first to start using clay models in a really significant way. In Vinton’s basement, they started experimenting with clay animation, with Vinton figuring out a way to use his camera to animate Gardiner’s sculptures.

Together, the two made a short film, Closed Mondays, from 1973-4, which found unexpected great success, winning the Oscar for Best Animated Short and connecting the pair to the wider animation world…

The film features a drunk man wandering around an art gallery, with the paintings and sculptures transforming into little vignettes elaborating on the artworks. Although the character animation isn’t as subtle as later stop motions would achieve, there are some really cool creative morphing effects and it’s got a ton of charm and creativity, no surprise people liked it!

They parted ways not long after that, with Gardiner focusing on PSA films in local politics, while Vinton founded a company called Will Vinton Animation Studios to further develop the stop motion animation, hiring on a handful of new animators who spent the 70s creating a trilogy of 27-minute animated fairy tales. During this time, he trademarked the term ‘claymation’, although it seems to have soon become genericised as other studios like the UK’s Aardman took up the technique.

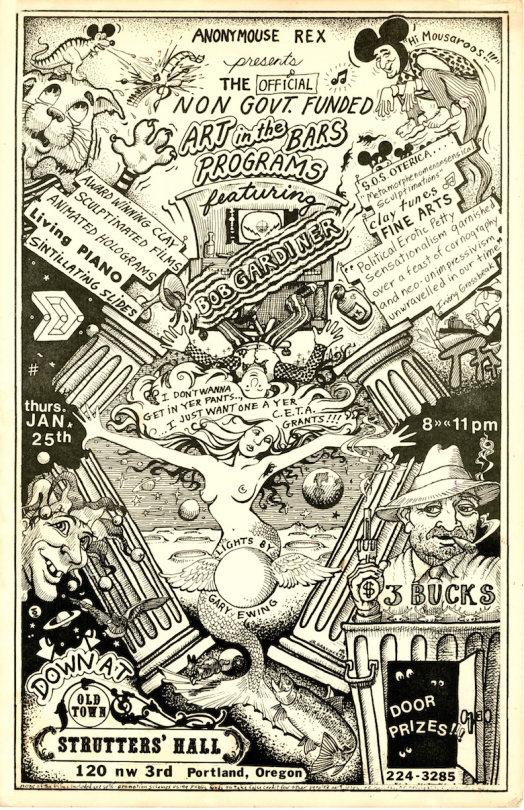

And while the rest of our story is gonna follow Vinton, let me quickly show you this cool poster that Gardiner produced in 1979:

“Political Erotic Petty Sensationalism granished over a fast of carnography and neo-unimpressivism”, what a statement lol. Anyway, let’s continue the Vinton story…

Hitting the 80s, Vinton and his studio moved up to 35mm film, continuing to make short films, music videos and adverts. They are responsible, among other creations, for the character ‘The Noid’ associated with Domino’s Pizza, and uh, read this sentence for me,

The California Raisins were a fictional rhythm and blues animated musical group as well as advertising and merchandising characters composed of anthropomorphized raisins.

America!

Moving into the 90s, they started switching from clay to moulded foam rubber, which apparently solved various production issues; using this technique, they animated Eddie Murphy’s series The PJs, which I managed to say almost nothing about back on Animation Night 21, as well as adult road trip comedy Gary & Mike. Unfortunately, this period was to be Vinton’s personal downfall…

Seeking to expand into feature films, Vinton sought outside investment, and found it from Travis Knight, the son of Phil Knight, who founded the Nike sports equipment company and thus must have more money than god. Travis had actually worked at the company as an animator himself, and so he must have seemed like the perfect investor.

Knight gradually became the majority shareholder in the company, and in 2002, as Vinton failed to secure more funding, Knight ousted him and took of the company completely. Vinton sued for use of his own name, and so in 2005 the studio was re-founded as Laika, with renowned stop motion director Henry Sellick of The Nightmare Before Christmas fame joining the company a year later. Soon they would become a major stop motion studio…

But what of Vinton? He founded a new, much smaller company to make stop motion animation called Will Vinton’s Freewill Entertainment, who made one short film, The Morning After, combining live action and CGI. Tragically, in 2006, he was diagnosed with cancer and retired from filmmaking in 2008. Still, he kept creating stuff in his last decade, including writing a musical The Kiss based on The Frog Prince and a graphic novel, Jack Hightower. Eventually, he died in 2018.

So, what became of the studio in the new hands? Their first film project saw Henry Sellick adapting a novel, Coraline, by Neil Gaiman, a British fantasy author who I find very annoying for entirely petty reasons. It was the perfect fit for Sellick, who likes to play in a sort of very stylised horror aesthetic while remaining ‘appropriate for kids’, and the studio brought an excellent design sense and a lot of compelling creepy images like the button eyes. The story sees a young girl called Coraline who’s drawn into a parallel world by the temptations of her stepford-smiling ‘Other Mother’, actually a child-consuming spider entity, who Coraline figures out how to outwit by exploiting the right fae tricks.

It was a strongly executed, visually striking film right out of the gates, and won Laika a lot of accolades - not to mention helping rebuild Sellick’s own reputation after he had once been under the shadow “hey, did you know Tim Burton wasn’t the director of The Nightmare Before Christmas?”

Unfortunately their planned second was cancelled and, ulp, the studio faced a wave of layoffs. The animation industry is not friendly to its animators!

The next film continued the halloweeny vibe, albeit more comedic, Paranorman - a film I haven’t seen about a boy who can see the dead that landed to another warm reception. Their next entry was a little less successful, in The Boxtrolls, adapting a children’s book; this one provoked a bunch of discourse on here I recall about some dumb man in a dress gag they threw in.

Then 2016 saw Kubo and the Two Strings, which took things to a Japanese-pastiche setting, and Travis Knight - the son of the Nike guy we mentioned above - stepping in to direct. Isn’t it nice when your dad can just buy out an entire animation studio for you? Still, he took on a very ambitious animation project, an adventure story about a travelling shamisen player, with some truly enormous stop motion models, and a studio whose character animation was refined by years of feature film production. It landed to enormous critical acclaim, and duly reaped its reward nominations.

Kubo, which takes inspiration from ukiyo-e in its visual design, follows in the footsteps of American productions like Avatar: The Last Airbender, Disney’s Mulan and Kung Fu Panda of taking a sort of more or less mythologised Asian setting… and like many of these projects saw only limited involvement of Asian people. This drew a certain amount controversy at the time, particularly in the casting; I’d be very curious how the film ended up being received in Japan itself. I’m not writing this to totally condemn, of course, it would be crazy for me to reject cross-cultural inspiration, it would ludicrous to say only the Japanese have the right to respond to Japanese history… but it definitely adds a contextual layer to know this vision of Japan comes from the son of a hyper-rich American businessman!

In a way, although Kubo is genuinely a stop-motion film, it’s a different flavour of stop motion due to the extensive amount of 3D printing involved in the production. I don’t know if it’s quite at the level of being ‘a CG film which uses physical models as its rendering engine’ but it’s an interesting evolution of high-budget stop motion. In all sorts of ways, the touch of the individual artist is pushed out - no more literally visible thumbprints, now we have a pipeline of hundreds of people to match the largest VFX house! (Later Aardman can feel the same.)

Presently the most recent film of Laika is Missing Link (2019), a lighter-hearted comedy about cryptids. I vaguely remember seeing marketing for it, but it doesn’t seem to have found a big audience in the way of some of their earlier films.

Overall, I’m not sure how I feel about Laika. Technically, their artists’ animation skills are inarguably fantastic: consistently strong visual direction, subtle and expressive motion, fantastic lighting work. There seems to be a real flair and evident passion to their best entries, rather than just soullessly presenting wildly expensive but meaningless animation. And, I will admit, however much his dad’s money opened the door for him, Travis Knight does seem to have done the work (even if his next film was uh a spinoff of the Transformers franchise sdfsdf? Showbiz, huh…). But there is something that rankles about Will Vinton being frozen out by the power of sporting goods capitalism. I don’t trust this new beast’s motivations!

Maybe I’ll feel differently after experiencing Kubo? We’ll see… As far as shamisen and biwa players go, I’ll definitely be thinking about Heike Monogatari and, whenever we actually get to see it, Masaaki Yuasa’s film Inu-Oh.

Tonight I’ll be travelling back to London by train; when I get back 1.5-2 hours we’ll watch Laika’s two most successful films, Coraline and Kubo and the Two Strings. I’ll post here once we’re ready to start! See you then~

Well, here’s the bit afterwards where I review the films :p

Coraline sadly did not hold up quite as well as I remember it. I remember the discourse of the time - this was 2009! - was very focused on like, #feminism - whether Coraline’s agency is compromised by writing Wybie into the last scene or whatever. Which seems to miss the far larger problem with the story in both book and film form: the arc of Coraline’s parents’ distance and neglect, which forms the entire motivation for the plot, is brushed over without a genuine resolution. She frees them from the evil faerie world (deciding they are, at least, better than a cool sexy spider mum who wants to eat her soul) but they have no memory of it, and they just kind of fall into being a family.

Like, basically, the resolution is that her parents succeed at business so they have time for their daughter and buy her the gloves she wanted; their role in the whole affair is never really addressed. Coraline just had to learn to suck it up. And since it’s framed as such a parable - a little bubble world where everything revolves around Coraline - it’s hard not to take it as an overt message.

(But that’s Neil Gaiman I guess lol. Smug git.)

Anyway Kubo and the Two Strings had a similar flaw, but its biggest problem was, sadly, being American. By far the worst issue is that the script has no faith that it can keep its audience’s attention without undercutting every scene with a quip every thirty seconds; it seemed constantly afraid to be sincere, like it was constantly turning to us and saying ‘yeah we know this is kind of goofy but bear with us’. The simplicity and narrow focus of the story wasn’t really a problem, but because it seems afraid to commit to its Japanese setting and keeps all mythological and place allusions as vague as possible, so it ended up falling back on a set of very American nuclear family tropes for characterisation. And like Coraline, it brushes over key moments of resolution - the heavily telegraphed reveal that the beetle guy was actually Kubo’s dad all along barely gets any time to land before he’s thrown offscreen and then soon after killed off.

The final confrontation with Kubo’s grandad, wherein grandad lays out his motivation, feels like it should be a key moment for pushing the thematic crux of the movie; but everything the ‘Moon King’ says falls flat for being unsupported by the rest of the narrative. He wants Kubo to be physically blinded to the pain and suffering of the world and live serenely in heaven, but Kubo instead committing to the physical world is a no-brainer rather than a serious choice; there are no conflicts in the movie that aren’t ultimately the Moon King’s fault, nor has the Moon King shown him the slightest sympathy before. Rather than a tragic figure, this heavenly king just seems like a total idiot.

The macguffin quest that drives most of the film also feels really boilerplate (and indeed, ultimately the macguffins are discarded, irrelevant), but a huge amount of time is spent on them. Kubo’s answer to the challenge presented by his grandfather - to draw on the power of the memory of his parents, represented by the ‘two strings’ of the title, with the corny line “memories are the most powerful magic there is!”, sadly did not cohere for me - I can see the elements they were trying to use to invoke the theme (many characters in the film have amnesia inflicted, Kubo’s whole quest is basically an excuse to build up a lot of family memories before they get killed off, his grandfather is trying to get him to forget these connections), but it feels like it never quite figures out how to push beyond cliché. It feels like it’s gesturing towards Buddhist and Confucian concepts but hasn’t quite figured out what it’s trying to say about them (ultimately, it seems opposed to them).

There’s also just smaller annoyances, like puns and jokes (Kubo calling the monkey statue ‘Mr. Monkey’ being treated as misgendering) that simply would not work in Japanese. The film’s opening act - honestly, the strongest part - takes place during the Bon festival, and I think they seriously put some effort into portraying that with the correct signifiers, but it feels like it either leaves out the context of the festival to an oblique mention, or belabours the point in the lantern ritual scene.

It’s a shame because visually, the film is very striking, with some really seriously impressive sequences like the final battle with the centipede monster or the underwater ‘forest of eyes’. It often feels much more like CGI than stop motion, as a result of both the 3D-printing replacement animation meaning everything really moves like CG rigs, the incredible amount of labour spent on secondary motion of hair and cloth, and at a few points actual CG VFX. Despite that, though, the use of real physical models and top tier lighting and compositing gives it a lot of visual weight which would be difficult to achieve in CGI - not impossible, but it’s an effort that pays off.

Some of the shots, like the ocean ones, I find it hard to imagine how they could have possibly accomplished in stop motion, but they have a really interesting sense of shape that makes me wonder if just maybe they had found some incredible trick to animate the surface of the ocean. But that’s probably CGI. It’s still fantastic the brief glimpse they give of the process of animating the skeleton rig, and I’d love to see some making-ofs for this film.

A film that was willing to commit to more than just a surface-level borrowing of Japanese signifiers (look! we have a big skeleton boss just like that famous ukiyo-e print! look, the Bon festival! look, origami!) but also put more care into matters like pacing and thematic content could have been incredible. Alas, it was all in service to something that could not escape being another American kids’ movie. Even so, I think it could easily be salvaged with a different edit. Cutting the quips, and honestly a lot of the other dialogue would make sense - it’s such a simple story that the visuals tend to pull most of the weight, and it could really put the attention on the character animation. The use of the shamisen in the soundtrack is of course very appropriate, but I think in many cases it could stand to distance itself further from Hollywood soundtrack norms, rather than using all too familiar ‘exciting action scene’ cues.

Apparently the Japanese dub was good. It would have been nice to be able to acquire that at some point, I’d be very curious what decisions they made in localising it.

Comments