originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/911350...

apophenic-ocelles asked:

Neutron stars are essentially spherical, which makes them topologically similar to a deformed ball. How big of a bat (cricket or baseball, and does it make a difference?) would you need to whack a neutron star into the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, what would it have to be made of, and how far away would you want from all this as it goes down?

This is apparently the 1000th post on this blog, so I’d better use it to answer the most awesome question I’ve ever received.

Right, what are we dealing with here? Let’s start by quickly going over what neutron stars are, for anyone who’s not familiar, and a quick chatlog about black holes.

So, what you’ve got is a big ball of stuff which is being held up from collapsing into a black hole only by neutron degeneracy pressure. It’s coated in super-strong polymerised iron, it has a ludicrous magnetic field, it’s spinning really, really fast, it’s about 10km across but in that size is packed the mass of several suns.

We want to hit this object with an impactor of some kind, ideally one resembling a cricket or baseball bat, though that might be a bit difficult.

The challenge

What does the impactor need to do? Well, our neutron star is probably orbiting happily in a more-or-less circular orbit around the centre of the galaxy. Our galaxy’s about a hundred thousand light years (100 kly) across, but the neutron star will probably be somewhere inside that; arbitrarily (since it probably doesn’t matter too much) call it 25 kly, about the same as our sun.

We can change its momentum exactly once, after which we rely on gravity to carry it the rest of the way to the centre of the galaxy. A straightforward way of doing this would seem to be to hit it hard enough in the direction opposite its orbital motion to cancel it out entirely, so that it simply falls directly into the centre of the galaxy.

The supermassive black hole in the centre of the galaxy at Sagittarius A* is believed to have a mass around 4 million times that of the sun, so its Schwarzchild radius is about \(10^{7}\unit{km}\), which is \(\about10^{-11}\) of the orbit of the neutron star. That is our target: if the neutron star goes inside the Schwarzchild radius, it is never coming out again.

For some comparison, a hole-in-one in golf (a subject I know nothing about, but think this is an incredibly difficult and impressive thing to do) generally involves knocking a ball into a hole about \(300\unit{m}\) away that has a \(0.05\unit{m}\) radius, merely \(\about10^{-4}\) of the distance to the hole, i.e. 10 million times more margin for error in the direction (because we can safely make the small-angle approximation here).

Mind you, we probably don’t need to get it quite that near for it to break up and accrete onto the black hole, or even just to curve in like any other massive particle. The precise details of a black hole-neutron star binary system seem pretty damn complicated, but the introduction does have a formula for the time it takes them to lose all their energy to gravitational waves and coalesce.

Then again, while a golf course may have hazards, at least they don’t gravitationally attract the ball while it’s in flight! Our neutron star will inevitably be drawn away from its course by objects it passes en route. Getting it to the centre would require incredibly detailed knowledge of the distribution of mass in the galaxy and equally sophisticated simulation ability.

The bat

OK, so what could we use to hit a neutron star so hard that it stops entirely (relative to the centre of the galaxy)?

Let’s first figure out how much momentum our neutron star needs to lose. It’s orbiting the centre of the galaxy at some speed, determined by its position on the galaxy’s rotation curve.

The rotation curves of galaxies is something astrophysicists are pretty interested in, because when we look at galaxies through our telescopes, they don’t act like we expect them to if they were just made of stars. This is one of the lines of evidence leading to the idea that there’s some kind of thing we don’t know much about, termed dark matter. I’ll talk a bit more about this later.

For now, we just need the orbital speed of our neutron star, which is the same as that of the sun, \(220\unit{km\,s^{-1}}\). The mass is between 1.4 and 3.2 solar masses; call it 2 solar masses. The neutron star’s momentum is then around \(9\times10^{35} \unit{kg\,m\,s^{-1}}\).

So, we need to hit this with an impactor which

- imparts this absurd amount of momentum in a precisely controlled direction

- does not splatter the neutron star into pieces

- does not add so much mass to the neutron star that the neutron star becomes a black hole

- is vaguely bat-shaped

Hmm.

The universe generally doesn’t have many collisions involving that much relative momentum. Neutron star collisions are a thing which happen, though - either neutron stars with other neutron stars, or neutron stars with black holes. (Ordinary stars, as I understand it, don’t so much collide as get torn to pieces and steadily accrete onto the neutron star.)

Briefly, neutron stars in orbit around each other steadily radiate away their energy and grow closer together. Eventually, they tear each other apart and merge, which very likely takes their combined mass over the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit and causes them to collapse into a new black hole over the course of a couple of seconds.

It looks something like this still from a NASA video.

In the process they create absurdly strong (even by neutron star standards) magnetic fields that last only a few milliseconds. This is thought to be the source of short gamma ray bursts, which are followed by flashes as the bits of neutron star that splashed out from the collision spiral into the black hole.

Oddly enough, these collisions make gold, and though rare, they’re apparently even thought to be the source of all the gold in the universe (or at least, so Wikipedia says). These collisions are also interesting because the spiralling neutron stars make (comparatively) lots of gravitational waves, which is something general relativity predicts but we haven’t directly detected.

That describes neutron stars in orbit around each other, a relatively comfortable situation compared to what we’re talking about. Still, it looks like we can maybe expect ludicrous magnetic fields, gamma ray bursts, gold forming, and bits of former neutronium going all over the place. It sounds pretty difficult to aim.

Anyway, it would be a bit strange to have our impactor be a neutron star, because if we can accelerate a neutron star to be our impactor, we could skip a step and do the same thing to the target neutron star straight away. The same probably goes for ordinary stars or black holes: whatever magic means we have to accelerate them would be more sensibly applied directly to the neutron star.

If we can’t make an impactor of many solar masses, an alternative might be to use a much lighter bat and achieve the necessary momentum by hurling it at relativistic speeds. We could even use an actual cricket bat! Even if we used the entire Earth, it would have to travel so close to the speed of light that Wolfram Alpha can’t tell the difference.

The problem I envision here is that a small relativistic ‘bat’, like an actual cricket bat, might punch straight through the neutron star and out the other side (albeit having completely disintegrated into a cloud probably) without imparting much momentum. It would probably create some pretty absurd shock waves in the neutron star surface though! A large ‘bat’ like a planet, meanwhile, would probably splash on the neutron star and smash itself to pieces.

Unfortunately I’m not sure I really know enough to make sense of the dynamics of a neutron star/relativistic impactor collision. For the next few sections, we’ll just assume that something like that is possible.

Falling neutron star

The mentioned coalescence formula concerns a black hole and a neutron star in orbit, but our poor neutron star is going to gain a huge amount of speed as it falls into the centre of the galaxy. To work out how fast it will come in, we need to know the density profile of the galaxy.

I’ve had a surprisingly difficult time tracking down a model of the density profile of our galaxy, but the basic structure seems to be like this:

- there are three main components: the bulge, the disk, and the halo. You add them up to get the density.

- the disk contains about \(6\times 10^{10}\) suns worth of mass. 95% of that is in the ‘thin disk’, and 5% in the ‘thick disk’.

- the halo contains about \(2\times10^{10}\) suns worth of mass.

- the disk falls off exponentially with radius, \(\Sigma(r)=\Sigma_0\exp\left(-\frac{r}{r_d}\right)\) The scale length of the falloff is about \(r_d=3\unit{kpc}\) (kiloparsecs).

- the dark matter halo has a more complicated shape and contains about 90% of the matter.

- the bulge is approximately spherical, falling off according to something like Plummer’s model.

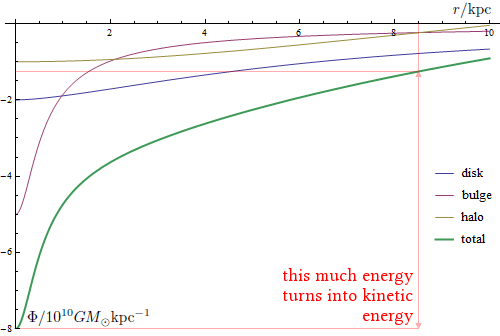

Because the Laplacian operator is linear, we can work out the potentials individually and add them together. We can then use this to work out the speed it arrives at the centre by just conserving energy.

The Disk

The potential of the disk turns out to be this mean looking thing involving Bessel functions (source):

In the plane of a thin disk with scale length \(r_d\) and central surface mass \(\Sigma_0\), the potential is $$\Phi(R,0)=-\pi G\Sigma_0 r [I_0(y) K_1(y)-I_1(y) K_0(y)]$$where \(y=\frac{r}{2r_d}\), and \(I_n\) and \(K_n\) are modified Bessel functions of the first and second kinds.

For the Milky Way, Σ0 can be set by integrating the exponential density profile over the entire plane to get the total mass Md of the disk (which we already have a number for): \begin{align}M_d &= \int \Sigma(r) \dif A \\ & = 2 \pi \int_0^\infty \Sigma_0 \exp \left(-\frac{r}{r_d}\right) r \dif r \\ & = - 2 \pi r_d \Sigma_0 \left[\exp\left(-\frac{r}{r_d}\right)(r+r_d)\right]_0^\infty \\ & = 2 \pi\, {r_d}^2 \Sigma_0\end{align}

Now the potential takes the form $$\Phi_d(r)=-\frac{GM_d y}{r_d} [I_0(y) K_1 (y) - I_1(y) K_0(y)]$$

We need to evaluate this potential in two places: the initial orbital position of our neutron star, and the centre of the galaxy. At the centre of the galaxy, the function approaches a limit of \(-\frac{GM_d}{r_d}\). At an orbit of \(25\unit{kly}\) which is about \(2.5 r_d\), it’s very roughly \(\frac{-GM_d}{2r_d}\) (actually more like \(-2.8G\Sigma_0 r_d\)). This means the potential difference - energy per unit mass which will become kinetic energy - is also \(\frac{-GM_d}{2r_d}\), in this case \(4.3 \times 10^{10} \unit{m^2 \, s^{-2}}\).

The Bulge

For the bulge, we’ll use the spherical Plummer model potential described here. It takes this form: \begin{align} \Phi_b (r) & = - \frac{G M_b}{r_b} \left(1+\left(\frac{r}{r_b}\right)^2\right)^{-\frac{1}{2}} \\ \rho (r) & = \frac{3 M_b}{4 \pi {r_b}^3} \left(1+\left(\frac{r}{r_b}\right)^2 \right)^{-\frac{5}{2}} \end{align}

We need to have a value for \(r_b\) if we’re going to use this model. The link has a page from a paper where two summed copies of this model was used to describe the Milky Way’s bulge, with the vast majority of the bulge being in the sphere with \(r_b=0.4\unit{kpc}\) rb=0.4kpc.

With this model, the potential difference between the centre (where \(\Phi_b=-\frac{GM_b}{r_b}\) and \(20r_b\) (where it’s about \(\frac{1}{20}\) of that) is pretty much the full \(\frac{GM_b}{r_b}\), or in this case \(2\times 10^{11}\unit{m^2\,s^{-2}}\).

The Halo

One potential yet remains: the dark matter halo. ‘Dark’ matter is something which we can only detect through its gravitational effects on everything else. It doesn’t otherwise interact much if at all with everything else, so we can’t see it with telescopes. Physicists are putting quite a lot of work at the moment into finding out more about it - there are a bunch of possible candidates that we’ve got theoretical descriptions of, but we don’t know which, if any, correctly describe this stuff.

Galaxies are thought to be embedded in a huge halo of this stuff. The halo has a lot of mass, but it’s spread out over a much larger volume than the rest of the galaxy, and I’m not sure how much effect it would have relatively close to the centre.

Astrophysicists have a number of different models for dark matter halos, the most popular apparently being the Navarro–Frenk–White profile. Rather than work out what the potential is for that, though, let’s go with something similar. In the same link that we found the Plummer potential, there's an excerpt of a paper that models a galaxy including a dark halo. It’s logarithmic, like so: $$\Phi_h(r)=\Phi_{h0}\log\left(1+\left(\frac{r}{r_h}\right)^2\right)$$

We’ll just use the parameters from that same link, setting \(r_h=8.5\unit{kpc}\) (pretty much exactly the orbital radius of the sun, and therefore our neutron star!) and \(\Phi_{h0}-G\times7\times10^{20}\unit{kg\,m^{-1}}\). The potential difference is then \(\Phi_{h0} \log(2)=0.7\Phi_{h0}\) per unit mass, in this case about \(3.4\times10^{10} \unit{m^2\,s^{-2}}\).

(Got to admit, this model makes me feel kind of uncomfortable. The potential just keeps growing and growing! I could possibly go and use the divergence theorem to find out if it contains an infinite mass, but this tangent is already too long.)

Adding them up

We could introduce further, smaller potentials, but I think (hope) we’ve got enough here to get a decent estimate of the speed the neutron star will arrive at now.

We’ve also, in the process, found this potential for our galaxy!

Marked on the plot is the total potential difference from the sun/our neutron star’s orbit, which is what we were looking for. It’s about \(6.7\times10^{10}G M_\odot\unit{kpc^{-1}}\), or \(3\times10^{11}\unit{m^2\,s^{-2}}\).

The speed of the neutron star is then \(760\unit{km\,s^{-1}}\).

How long would it take to fall in? This one’s a bit harder to work out, but we can do it numerically, using Mathematica. I set myself up for a massive unit headache here (“So, it hits the centre at 7.7. That’s 7.7 what?”) but after tracking the various kiloparsecs through the equation of motion, it takes about 36 million years. (If it had its final speed from the beginning, it would do it in just 10 million years. Light could do it in just 28,000 years.)

It’s a big galaxy.

Neutron star meets black hole

Our neutron star floats through the galaxy and arrives at Sagittarius A* at around 760km/s.

Outside the inner several Schwarzschild radii, Schwarzschild black holes act a lot like a Newtonian point mass. We can use a normal Newtonian hyperbolic trajectory until it gets close. (This approximation isn’t necessary, since for Schwarzschild black holes we can describe all the orbits analytically. This approximation is a great deal more straightforward, though.)

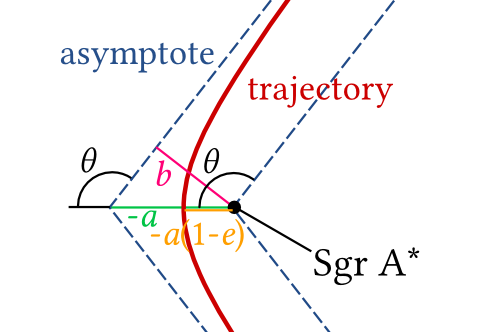

So, we have a hyperbolic orbit with a speed 'at infinity' (rather, when it's far enough away that the black hole's influence becomes less important than the rest of the galaxy, which we'll equate to the speed when it arrives at the vicinity of the black hole) of 760km/s. This implies the semi-major axis of the hyperbola is \(a=-6620\unit{AU}\). (For some reason, the convention is that a is negative for a hyperbola, which seems needlessly confusing). The distance of closest approach is then \(-a(e-1)\), where \(e\) is the eccentricity of the hyperbola.

The eccentricity essential depends on how well we’ve lined the neutron star with the black hole. OK, so imagine that the black hole had no gravity, and the neutron star just flies past in a straight line. The closest that line gets to the black hole is \(b\), the impact parameter. Based on the diagram and the property that \(\cos(\theta)=-\frac{1}{e}\), this is related to the eccentricity by $$e=-\frac{b}{2a}+\sqrt{\left(\frac{b}{2a}\right)^2+1}$$

Then the distance of closest approach is given by $$-a(e-1)=\frac{b}{2}+a+\sqrt{\left(\frac{b}{2}\right)^2+a^2}$$

As we’d expect, this goes to 0 when \(b\) is 0.

We want to get this distance to be around, say, order of magnitude 10 Schwarzschild radii, by which point the general-relativistic effects are going to become quite serious. For Sagittarius A*, the Schwarzschild radius is about \(0.08\unit{AU}\), so we want to get it down to about \(1\unit{AU}\). This implies \(b\) needs to be about \(2\unit{AU}\).

What’s \(b\) likely to be? Way too big. Suppose we manage to get our neutron star to go in almost the right direction, but get the angle wrong by a few fractions of a radian. We’re in the small angle approximation here, so we multiply that mistake by the \(8.5\unit{kpc}\) between us and the centre. Uh-oh. \(8.5\unit{kpc}\) is an awful lot. We need to be accurate to within \(10^{-9}\) radians (\(7\times10^{-8}\,{}^{\circ}\)).

So (the tl;dr version)…

It’s hard to think of any object which could impact a neutron star precisely enough, since you need to be accurate within \(10^{-9}\) radians. It’s even harder to imagine one that would survive, or that resembled any kind of bat. The impact could involve all kinds of nasty business, like squirts of superheated neutronium turning back into atoms like gold, and overwhelmingly intense gamma ray bursts and magnetic fields.

Supposing you managed it, though, and you used to to put the neutron star into direct freefall to the centre of the galaxy, it could get to the centre of the galaxy over the course of 36 million years. If you’re lucky, it seems like it could dump its energy through gravitational waves and be torn apart swallowed up by the black hole.

If you got it even slightly wrong, the neutron star would zoom around the black hole (acting much like the nearby stars) and fly away out from the centre again, slowing back down to \(760\unit{km\,s^{-1}}\) as it leaves the black hole. I imagine from that point it will fly some kind of complicated rosette over the next few million years.

(Please let me know if you have any good ideas for a suitable bat, or know of any work that’s been done on neutron star-relativistic impactor collisions!)

Comments