Today I was looking at electric fence battery that my parents use to keep ponies in a field. The battery in question produced a potential difference of \(12\unit{V}\), and stored a total of \(100\unit{Ah}\) (amp-hours) of charge.

I had the thought like, OK, when a battery is fully charged, it will weigh ever so slightly more than it does uncharged, due to mass-energy equivalence. By applying \(E=mc^2\), we can work out precisely how much heavier: in this case, it turns out to be \(48\unit{ng}\).

While I don’t know the precise model of this particular battery, a different battery with the same charge and voltage weighs just under \(30\unit{kg}\). So, we’re converting \(1.6\times10^{-10}\%\) of the battery’s mass-energy into other forms: in this case, energy imparted to electrons flowing in the wire. This energy is liberated by chemical reactions in the battery: electrons in the shells of atoms inside the battery transition into lower-energy states.

Well, I think 0.0000000001% of the mass-energy of the battery is pretty pathetic. Can we do better?

Nuclear reactions

It’s unlikely that we’d find a chemical transition that would beat that. I mean, maybe we could set the battery on fire, i.e. add some highly reactive oxygen and liberate energy that way? But, it wouldn’t be orders of magnitude difference.

Nuclear reactions, on the other hand, are much more energetic than chemical ones. Oh yes.

There are two relevant types of nuclear reaction if you want energy out: nuclear fission and fusion. In a fission reaction, one atom splits into two smaller atoms, plus a few other particles such as neutrons, electrons and neutrinos; in a fusion reaction, two atomic nuclei come together to form a new combined nucleus. Depending on the atoms under consideration, one or other will give out more energy.

Which one depends on the nuclear binding energy. A helium molecule weighs slightly less than two protons and two neutrons: this ‘mass defect’ corresponds to the ‘binding energy’ of helium, i.e. ‘a helium atom’ is a lower-energy state than ‘some protons and neutrons floating around’. When particles come together to form a helium nucleus, it is that binding energy which is imparted to the reaction products (in one chain, that’s the helium nucleus itself, neutrinos, positrons, unfused hydrogen nuclei and gamma rays); conversely, to split a helium atom into protons and neutrons, that much energy would need to be imparted.

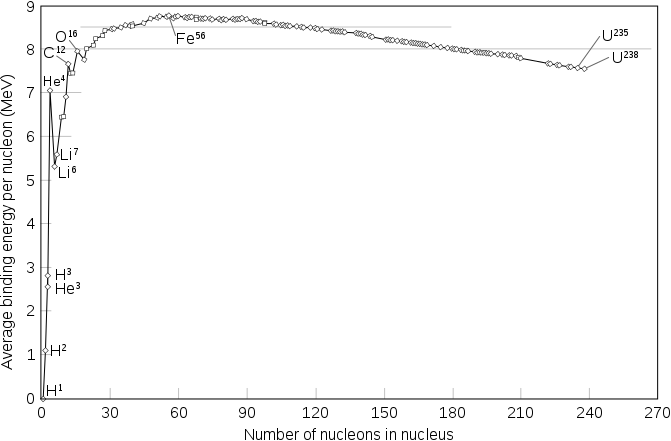

For atoms heavier than iron-56, the opposite is true: energy is released when they split apart, and fusion to make an atom heavier than iron-56 absorbs rather than releases energy. We can plot the binding energy per nucleon (i.e., energy needed per proton or neutron to split an atom into free protons and neutrons) for all atoms:

In general, we can say atoms ‘want’ to move towards iron-56, in the sense that nuclear reactions that move towards iron will be exothermic.

Binding energy is certainly not the whole story of which atoms are stable - otherwise there would be no atoms heavier than iron! - and endothermic reactions can still happen when there’s a huge amount of energy about - which really only happens for a brief instant in a supernova, but that (and subsequent nuclear decay) is enough to produce all the elements heavier than iron in the natural world.

On the other hand, even forhighly exothermic reactions such as hydrogen fusion, the reactants must have enough kinetic energy and a high enough collision rate to overcome the ‘energy barrier’ between the two stable (low-energy) states, which means a lot of heat or pressure or both. This is why fusion reactions aren’t happening all the time: nucleons are very happy to be fused, but it’s incredibly hard to get them there.

Anyway, for our purposes, we want to get energy out, as much as possible, so all we’ll worry about is binding energy and leave the rest to ‘implementation details’.

So, what atoms are present in a battery?

The first search hit with these battery specs is a lead-acid battery, meaning that its chemical-components are lead, sulphur, oxygen and hydrogen. That’s a common kind of battery, so let’s go with that. They react according to

\[\mathrm{Pb^{(s)}+PbO_2^{(s)} + 2H_2SO_4^{(aq)}\rightarrow 2PbSO_4^{(s)}+2H_2O^{(l)}}\]Of these atoms, the most promising for nuclear fusion is the hydrogen. So, how much hydrogen is there in a lead-acid battery? We’ll ignore the casing and just focus on the reactants. The sum of the molecular masses of the reactants is \(642.6 \unit{g\,mol^{-1}}\) (that is, per mol lead - it’s per two mol water), which means our \(30\unit{kg}\) battery contains (in its fully discharged state) about \(93\unit{mol}\) of water. That means \(186\unit{mol}\) of hydrogen.

How much energy can we liberate by fusing this hydrogen? Well, this is complicated, depending on such questions as how far we take the fusion, and which process we do it by. Let’s take a first target of fusing all of that hydrogen into helium using the proton-proton chain, which is the primary source of energy in low-mass stars like our sun. In each cycle of the proton-proton chain, four hydrogen atoms are eliminated, producing a helium nucleus, two positrons, and two electron neutrinos:

\[\mathrm{4p\rightarrow {}^4_2He + 2e^+ + 2\nu_e}\]This takes place in various steps, and the positrons annihilate with electrons and stuff, but the upshot is that you lose four hydrogens and get \(26.732\unit{MeV}\) out. Wikipedia notes that this is \(0.7\%\) of the mass of the original four protons.

How much of the mass of our lead-acid battery is protons? Well, if we have \(186\unit{mol}\) of hydrogen, that masses \(0.187\unit{kg}\), and if we’re getting \(0.7\%\) of that out as energy, we’re getting \(4.4\times10^{-3}\%\) of the original \(30\unit{kg}\) mass of the battery out of energy. That’s an improvement by a factor of over ten million, which ain’t half bad.

We could consider other potential ways to liberate energy in the battery using nuclear reactions, but my guess is that the hydrogen fusion is going to be by far the biggest factor in terms of energy contribution.

“Just implementation details”?

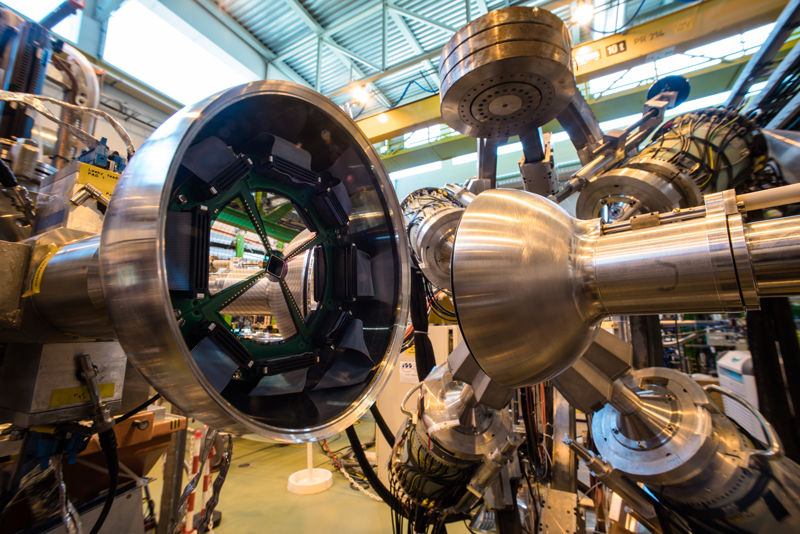

How would we actually go about doing that, and in what form would the energy be usable? Well, practically speaking, there’s no real way we could make all the hydrogen in the battery fuse. Even in a star, not all the hydrogen has fused by the time it starts burning heavier elements and eventually dies. In a tokamak or other magnetic confinement fusion reactor, only a small proportion of the hydrogen in a ‘shot’ will undergo a nuclear reaction. Additionally, fusion research largely focuses on the ‘easier’ fusion of deuterium and tritium (heavier isotopes of hydrogen), not the proton-proton chain.

Regardless, if we got the reaction to happen somehow, the energy would be imparted to the particles, giving them high kinetic energy; in other words, it would serve to heat up the plasma (we’d definitely have to have turned our battery into a plasma, i.e. vaporised and ionised it). Turning that heat into usable work is another challenge in fusion reactor design, but that’s more because of the absurd temperatures and radioactivities and vacuums involved; with a huge amount of heat, in the abstract you can use a heat engine to turn it into work with some efficiency.

But, hey, I think we can do a whole lot better than a piddling \(0.0044\%\) of the mass-energy of our battery.

What if we dropped it in a black hole?

On the face of it, that sounds ridiculous. If we drop it in a black hole, what good does it do us? It’s on the other side of the event horizon, permanently inaccessible.

(A black hole is an object so tightly compacted that not even light can escape from inside a certain radius, called the event horizon. They don’t crop up in Newtonian physics, but they do in general relativity. Near the event horizon, all kinds of weird spacetime effects happen, such as ‘frame dragging’ and ‘gravitational lensing’, that mess with our intuitive ideas of how physics works. Black holes aren’t really ‘holes’, but spherical or ellipsoid objects; the ‘hole’ metaphor is just that anything that passes inside the event horizon can never leave. You can’t really see them directly, since they don’t radiate any meaningful amount of light and absorb all light that goes inside them; they do, however, distort the light passing near them, creating strange visual effects.)

Oddly enough, while black holes themselves let nothing out from inside the event horizon, black hole accretion discs are one of the most efficient means to turn mass into energy in the universe, and therefore some of the brightest objects we can observe.

So how does that work out? Well, until you get quite close, a black hole is just like an ordinary massive object like a star or planet in Newtonian physics - just a whole lot more compact. But, any spherically symmetric object acts like a point mass to stuff outside it - so it doesn’t matter how small it is. So, if you’re flying in the vicinity of a black hole, you won’t necessarily fall in. You’d orbit it, like anything else.

However, suppose you’ve got a big star or cloud of gas or something. The cloud will be drawn in towards the black hole, gaining speed as it falls in, but it will also interact with itself. As the cloud collapses, the random motions in the gas parallel to the total angular momentum vector average out through collisions, and the whole thing ends up spinning around some axis - and as the cloud shrinks, it spins faster and faster, resulting in it spreading out into a large flat disc.

This is more or less stable, but not quite. This disc will be very hot, as all the kinetic energy gained from falling inwards is randomly spread around as heat. Because of that, it will radiate electromagnetic radiation. As they lose energy to radiation, the particles in the disc move to a slightly tighter orbit; they shed their angular momentum through friction to an outer part of the disc, heating it up, and find themselves in a slightly smaller stable circular orbit. Over time, they keep doing so, slowly migrating in from the edge of the disc until they reach the black hole’s minimum stable orbit; after that, they spiral rapidly into the event horizon.

But to get from the edge of the accretion disc to the minimum radius requires them to dump a whole lot of radiation. How much is possible?

Accretion physics is extraordinarily complicated, and there are a number of aspects that are still not fully understood (such as jet formation, or where the viscosity between annuli comes from). But, we can abstract away a lot of the details to get a decent approximation.

Black holes come in various kinds, depending on whether they are rotating, charged, or both. The simplest kind is a nonrotating, uncharged black hole, which is called a Schwarzschild black hole. Since we want to make things as simple as we can, we’ll use one of them to get our first approximation. As mentioned above, a Schwarzschild black hole has a minimum stable orbit inside of which any nearby matter will inevitably fall beyond the event horizon; this is three times the Schwarzschild radius, \(R_\mathrm{S}=\frac{2GM}{c^2}\). So \(3R_\mathrm{S}\) marks the inner limit of our accretion disc.

There is a lot of interesting physics in accretion discs, which I spent a while copying out and explaining just now… but then deleted, because actually we don’t need any of that to calculate the energy that must be radiated as a particle migrates in to the black hole. If you’re interested, there are some Oxford University lecture notes available online here (caution: there are a couple of typos I’ve found, e.g. in calculating the density profile of the thin disc). For a more general treatment that uses the machinery of Navier-Stokes etc., my astro fluid dynamics lecturer at Cambridge wrote this book on all things to do with astrophysical fluid dynamics, and it has a chapter on accretion discs.

But for a pretty good approximation, we can treat the black hole potential with a Newtonian potential (which the Schwarzschild metric reduces to as you get far enough away). At any given point, a particle is very close to being on a Keplerian orbits (this is its osculating orbit, incidentally), so we can calculate its orbital energy. I’ve talked a bit about orbits and orbital energy in this post on flying rockets. For an elliptical orbit, we have

\[E_\text{orbit}=-\frac{GMm}{2a}\]where \(a\) is the semi-major axis; setting \(a=3R_S\) gives us the specific orbital energy of the innermost stable orbit. Assuming the particle started with just enough energy to escape the black hole, and all that energy has been radiated away as it sinks down to the accretion disc, the total amount of energy that has been emitted is \(-E\). This means the proportion of mass-energy we can extract by accreting an object onto a Schwarzschild black hole is

\[\frac{-E_\text{orbit}}{mc^2}=\frac{GM}{6c^2 \cdot \frac{2GM}{c^2}}=\frac{1}{12}\]That is, \(8.3\%\) of the total mass-energy, about a thousand times better than the fusion case, and ten billion times the energy we get from discharging the battery normally. In fact, we can do a lot better: for a rapidly rotating black hole, the innermost stable orbit gets much closer to the event horizon, and we can (apparently) extract a full \(42\%\) of the mass-energy of our battery!

Caveat: if we just had a black hole floating in space, and dropped a single battery in, that wouldn’t do much at all - the battery would either orbit the black hole, or just go straight in. To really get this absurd amount of energy out, it’s crucial that our battery spirals slowly into a black hole in a big cloud of gas.

Now, you might say, just find a black hole that’s busy eating a star or something and add the battery to the mix. But no! Getting energy from any source other than batteries is cheating. No, we need a lot of batteries, and a black hole big enough to be stable in the middle of nowhere, and we will feed so many batteries into the black hole that they’ll make an accretion disc all on their own.

Assuming the infalling matter is coming in as fast as it physically can - the Eddington limit, described in the links above - and that vaporised batteries act a lot like ionised hydrogen (probably wouldn’t for all that lead etc.!), and using a Schwarzschild black hole that is - say - the mass of the sun, we might find

\[\dot{M}_\text{Edd} = \frac{4 \pi GM m_\mathrm{p}}{\epsilon c \sigma_\mathrm{T}}=1.7 \times 10^{15} \unit{kg\,s^{-1}} = 5.6 \times 10^{13} \unit{batteries \, s^{-1}}\]So, if you have a solar mass Schwarzschild black hole, you could turn batteries into energy with \(8.3\%\) efficiency at a rate of 56 trillion batteries every second. It would still take you about a billion seconds, or 100 years, to dispose of an Earth mass of batteries in this way.

We’re not done with black holes yet, though. There’s another method to extract energy from black holes, theoretically: Hawking radiation. (Or, if you prefer, Hawking-Zel’dovich radiation, because apparently Hawking got the idea from a couple of Soviet physicists? I had no idea.)

Are you going to tell me you understand Hawking radiation?

Lol, no, my understanding of Hawking radiation is no better than the pop-sci treatment. My understanding of QFT is way too wobbly to be able to follow the argument.

The basic idea, however, is if you try to work out a quantum field theory in the vicinity of a black hole’s event horizon, you end up finding that the black hole must be radiating energy, with a black body spectrum. The temperature of this black body radiation is determined by the mass of the black hole; the bigger the black hole, the ‘colder’ the radiation. For a Schwarzschild black hole, the radiation is (per Wikipedia)

\[T={\frac {\hbar c^{3}}{8\pi GMk_\text{B}}}\quad \left(\approx {\frac {1.227\times 10^{23}\unit{kg}}{M}}\;{\text{K}}=6.169\times 10^{-8}\unit{K}\times {\frac {M_{\odot }}{M}}\right)\]which means that for a solar mass black hole it’s only ten billionths of a Kelvin, but for a really really tiny black hole it’s much faster. The total energy radiated by a black hole over the time it takes to evaporate is of course the mass-energy of the black hole; but the time it takes is very, very long. In 1976 someone called Don Page worked out how long it would take a black hole to evaporate using the known particle interactions at the time, and found that it takes

\[\tau=\alpha \times 10^{-36} M^3 \unit{s kg^{-3}}\]where \(\alpha\) is either 4.8 or 8.66 depending on which range of masses the black hole falls into. For a solar mass black hole, or even an Earth mass black hole, that’s an incomprehensibly huge multiple of the age of the universe, but for a black hole the size of, say, a \(30\unit{kg}\) lead-acid battery [if this formula even applies at that size, which it does not!], that’s only \(0.1\unit{ps}\) - a tenth of a picosecond. Of course, the hard part would be squashing the battery down to a \(4.5\times 10^{-26}m\) radius, which is much smaller than even a really high energy gamma ray.

How many batteries would we need for a nice intermediate value, where we can harvest the energy in, say, a year? And how small would the black hole be?

Reversing the equation, we have \(M=\sqrt[3]{\frac{\tau}{\alpha}\times 10^{36} \unit{kg^3\,s^{-1}}}\)and plugging one year into that we find the black hole needs to mass a good 150 trillion kg, which is apparently twice the total biomass of Earth and 1.5 times the total mass of all oil produced since 1850 (thanks, Wolfram Alpha!).

How many batteries is that? About five trillion - \(5\,000\,000\,000\,000\). We just need to compact all those batteries into \(228.5\unit{fm}\), which is on the scale of subatomic particles, and then we can harvest our \(1.4 \times 10^{31} \unit{J}\) at our leisure over the following year. Yeah, good luck with that. We’d obtain about a tenth of the energy we’d need to completely atomise the Earth into an infinitely big cloud of space gas, if you’re wondering.

This hypothetically gives us \(100\%\) of the mass-energy, in the forms of high-energy gamma radiation - we’re talking a black hole of temperature \(8.18\times10^{8}\unit{K}\), with the energy spectrum peaking in the gamma range for \(200\unit{keV}\) rays. But I guess if you can crush five trillion batteries into the size of a subatomic particle, you can probably handle a lot of gamma radiation.

But there’s another way to extract all the energy. You might say it’s an easier way, but only in the sense that there’s more reason to think it could be done theoretically in principle, given unlimited time and resources.

Antimatter

An interesting thing to spin out of quantum field theory is that particles all have antiparticles (though some particles are their own antiparticle), which are like the particle in almost every way except for having the opposite charge (and some esoteric but important things to do with CPT symmetry breaking down). A particle can interact with its own antiparticle to annihilate, replacing the original particle-antiparticle pair with some new particles with the same total energy and momentum as the original particles.

The advantage of this is that it can be used to extract all the mass-energy of a particle - assuming you can do something with really high energy particles, anyway.

An electron and a positron annihilate to produce a pair of very high energy gamma rays (or perhaps only one if there’s a charged particle nearby). The rest energy of the electron and positron (and their kinetic energy, but that is likely negligible unless they’re going near lightspeed) give the photons their huge energy. More complicated particles, such as protons antiprotons, annihilate in a complicated way to create, ultimately, electrons, positrons, gamma rays and neutrinos, collectively having the rest energy of the original proton-antiproton pair. If an antinucleon annihilates inside a more complicated nucleus, it causes a right mess, which can cause - for example - a nucleus to burst apart in a shower of high-energy neutrons useful for causing nuclear fission. Etc., etc.

The short version is, particles and antiparticles come together, a whole lot of energy becomes available in other forms.

(Pop-sci sometimes speaks of particles and antiparticles annihilating to make ‘pure energy’ which is a nonsense term. But, in terms of the basic idea of, particles and antiparticles come together and there’s a huge explosion, that’s about right.)

So, how do you make an anti-battery to annihilate with the particles of our battery? Well, we do actually have means to produce antimatter, but the amounts are tiny and it’s almost impossible to store. But… according to a recent Nature announcement, scientists are hoping to carry about a billion antiprotons around in a van (!!!) in the next four years. Now, a billion antiprotons is not a lot of mass, about \(1.6\unit{fg}\) so we’d need \(30 \times 10^{18}\) of that to make a battery’s worth. Still, I had no idea that was even that close to being possible!

Anyway, we don’t just need to store antimatter, we also need to make it. Per Centauri Dreams, a scientist called James Bickford has proposed scooping naturally occurring atmosphere up from space. The system envisioned would apparently have the potential to collect around \(25\unit{ng}\) per day. To produce \(30 \unit{kg}\), we’d need a good trillion days, or about 3 billion years, comparable to the age of the Earth. Haha, yeah, no.

Winchell Chung at Atomic Rockets makes some estimates of how quickly we could make antimatter ourselves. The answer: very, very slowly. He refers to a novel by George Zebrowski and Charles Pellegrino (creator of the ‘Valkyrie’ antimatter starship, perhaps the least implausible interstellar spaceship… I’ve never read his novels, I just like the spaceship!)…

In Charles Pellegrino and George Zebrowski novel The Killing Star they deal with this by having the Earth government plate the entire equatorial surface of the planet Mercury with solar power arrays, generating enough energy to produce a few kilograms of antimatter a year (and enough waste heat to make the entire planet start to vaporize). They do this with von Neumann machines, of course. The novel needed antimatter fuel, because when you are trying to delta V a starship up to \(96\% c\) and back down, you are going to need a lotta energy.

As a first approximation, imagine Mercury had been replaced by a flat disc of solar cells with the same radius as Mercury (about 2,440,000 meters radius). Area of about \(1.87\times10^{13}\) square meters. Solar flux at Mercury’s orbit is about \(9\,121 \unit{W\,m^{-2}}\) so we are talking about approximately 170,562,700,000,000,000 watts (0.17 exawatts).

So if the entire disc is covered in solar cells, and the cells have a magical efficiency of 100%, and the antimatter factories are Dr. Forward’s 0.0001 efficient designs, it could crank out one kilogram of antiprotons every one and one-half hours.

If the disk is only 1/3rd covered in solar cells (Equator), and the cells have a NASA standard efficiency of \(29\%\), and the antimatter factories have the current efficiency of 0.00000002, then it could eventuallly spit out one kilogram of antiprotons after 8.6 years of continuous operation.

So, if we just cover a third of the planet Mercury in solar panels with self-replicating machines, we could churn out a battery’s worth of antimatter in a few centuries. Then, we use it to blow up our other, ordinary battery… or we could just use the solar panels for something else.

Anyway, even if you have equivalent masses of antibattery and battery, actually getting the full battery’s worth of energy would be another challenge. There’s quite a bit of argument among the kind of nerds who argue about how spaceships would best blow each other up regarding what would happen if you ram some antimatter into some matter. I am not going to venture to guess the best way, but it seems like maybe with the right setup you could make most of the battery get annihilated? Worst case, you feed it atom by atom into a particle accelerator…

Gathering this energy is another problem. Apparently pions are your best bet?

So… how much energy could you get from a battery?

If we pursued one of these elaborate schemes to use antimatter or black holes to turn the battery into a lot of high-energy gamma rays (and other particles), and we were somehow able to use all of those gamma rays, we could get \(3 \times 10^{18} \unit{J}\) per battery. That’s apparently about \(20\%\) of the total electrical energy production in the USA in 2001. Not bad… but maybe not worth the trouble.

Comments