Earlier this year, private spaceflight company SpaceX launched a car into space to test their new Falcon Heavy rocket.

A car, of course, cannot drive in space, so to get to its eventual destination of flying by Mars, the car must be pushed around by a rocket. But why is this?

Space is a very different environment to Earth. On Earth, there is always something around you: the ground, water, air. This gives you something to push off, so acceleration is easy. But friction and air resistance will always slow you down as you move around, so without constant work to maintain your speed, you will slow back down to a stop.

In the vacuum of space, a spacecraft need not worry about friction, and it can fly on forever at the same speed without any work. However, when it wants to change its speed or direction, it has no convenient ground to push on. It has to do something else.

What is this?

This is a course of questions designed to teach you about the rocket equation through active learning, inspired by brilliant.org. (Full disclosure: I’m writing this to apply for a job there.)

Assumed knowledge & what you’ll learn

I’m assuming you know:

- how to solve a mechanics problem by conserving momentum and transforming between reference frames

- how to differentiate and partially differentiate simple functions

- how to solve an integral of the form \(\int\frac{1}{x}\dif x\).

In the process of this course, we’ll see

- how to express conservation laws with the differential of a function

- how to derive the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation using differentials

- the meaning of delta-v, specific impulse and the mass ratio

- how to use the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation using values from real spacecraft

If you’re especially keen, open the ‘aside’ boxes for extra details and extensions, such as:

- the nature of differentials

- deriving the relativistic rocket equation using rapidity coordinates (make sure you’re comfortable with hyperbolic functions)

[nb these extra boxes could be expanded into their own courses of questions later, but I think it’s useful to put them next to the relevant bits of the course. Consider them optional extras.]

Contents

- Question 1: How to move in a vacuum

- Question 2: Splitting the reaction mass

- Information: What is a rocket?

- Question 3: Setting up the situation

- Information: Differential of a function

- Question 4: Computing a differential

- Question 5: What does a rocket conserve?

- Question 6: Conservation laws as differentials

- Question 7: Obtaining the rocket equation

- Information: A little terminology…

- Question 8: Does thrust matter?

- Question 9: Using the rocket equation directly

- Question 10: Using the rocket equation in reverse

- Information: Staging

- Challenge question: the Saturn V

- Conclusions

Question 1: How to move in a vacuum

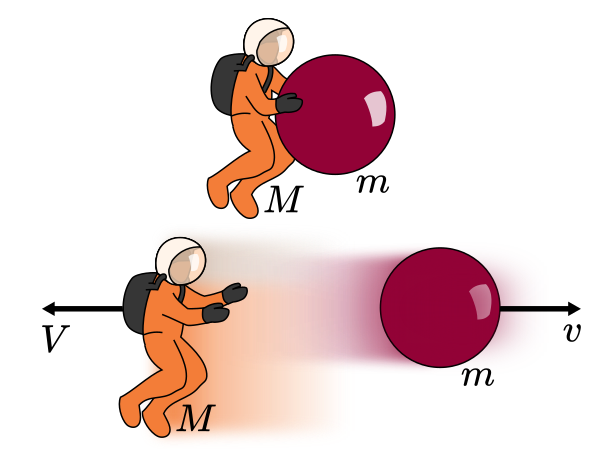

An astronaut Mae, who is of mass \(M\), is floating on a spacewalk somewhere deep in space. We are looking at her in a frame of reference where she is initially stationary.

Mae would prefer not to be stranded in space, but she had the foresight to bring a large bowling ball of mass \(m\). She throws the ball away from her with speed \(v\), causing her to travel in the opposite direction with speed \(V\).

What is the relationship between \(V\) and \(v\)?

- \[V=v\]

- \[V=\frac{m}{M+m}v\]

- \[V=\frac{m}{M}v\]

- \[V=v\log\frac{m+M}{M}\]

Solution

In this problem, momentum is conserved. (Kinetic energy is not conserved, because the throwing the ball introduces new kinetic energy, transformed from the chemical energy in Mae’s arms.)

Initially, nothing is moving, so the total momentum is zero.

After Mae has thrown the ball, the total momentum becomes

\[mv + M \cdot (-V)\]By conservation of momentum, the total momentum must be the same in both cases, so we have

\[mv-MV=0\]which we can rearrange to find

\[V=\frac{m}{M}v\]Question 2: Splitting the reaction mass

Mae’s bowling ball illustrates one way you can change your velocity in space: take a part of yourself, and push it away from the rest of you, making you accelerate in the opposite direction. The stuff you throw away is called reaction mass, because the reaction from pushing it away is what causes you to accelerate.

Rockets, however, do not launch all their reaction mass in one go, but release it over time in a steady stream. As a first step, let’s consider what happens if you release your mass bit by bit.

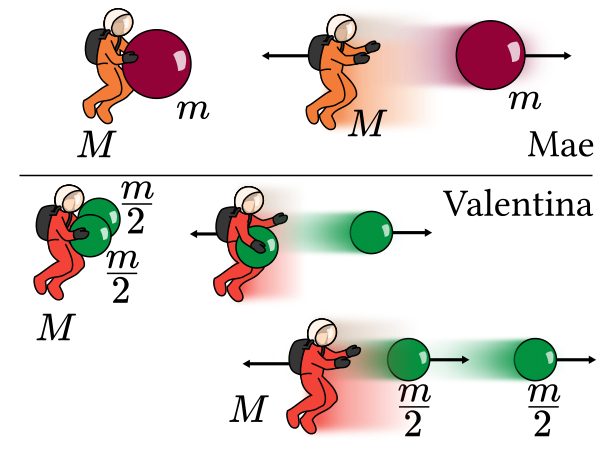

Mae goes on another spacewalk, and this time she’s joined by Valentina, who has the same mass as Mae, but has brought two bowling balls of mass \(\frac{m}{2}\).

Mae once again has one large bowling ball, of mass \(m\). Mae throws her bowling ball at speed \(v\); Valentina throws both her bowling balls, first one then the other, both at speed \(v\) relative to herself.

Which of the two astronauts will be travelling faster after all these bowling balls have been thrown?

- Mae

- Valentina

- They will move at the same speed

(Hint: don’t try to calculate it in detail! But if you want to see the full solution, check the ‘extra details’ box in the solution.)

Solution

When Mae throws her ball, as before, she ends up at speed \(V=\frac{m}{M}v\).

When Valentina throws her ball, you might imagine that throwing a ball of mass \(\frac{m}{2}\) would give her a speed \(\frac{V}{2}\). This is true for the second ball she throws. But Valentina isn’t just pushing her own mass when she throws the first ball, but also the mass of the other ball. So she’ll gain less than \(\frac{V}{2}\) speed from the first ball, and her total speed will be less than \(V\).

For that reason, Mae will end up travelling faster.

Extra details

We can work out exactly how fast Valentina is going. After she throws the first ball, we’ll say she has speed \(V_1\). We conserve momentum as before, but this time the ball thrown has mass \(\frac{m}{2}\), while the mass of Valentina and the second ball together is \(M+\frac{m}{2}\). This means we get

\[\frac{m}{2}v-\left(M+\frac{m}{2}\right)V_1=0\]so after the first ball, Valentina has speed

\[V_1=\frac{m}{2M+m}v=\frac{1}{1+\frac{m}{2M}}\]We can then transform to Valentina’s rest frame, and do the same calculation we did for Mae. So we find, in this new frame, which is moving with speed \(V_1\) relative to the original, Valentina has speed

\[V_2'=\frac{m}{2M}v\]Working out her total speed requires us to crunch a bunch of algebra. To simplify, let’s define \(x=\frac{m}{2M}\). Then,

\[\begin{align} V_1&=\frac{1}{1+x}v \\ V_2'&=xv \end{align}\]Then, to find her total speed in the original frame, we transform back:

\[\begin{align} V_2&=V_2' + V_1 \\ &= \left(\frac{1}{1+x}+x\right)v \\ &= \left(\frac{1+x+x^2}{1+x}\right)v \\ &= \left(\frac{1+x+x^2}{2x(1+x)}\right)V \end{align}\]where \(V=2xv\) is the speed of Mae.

The fraction \(\frac{1+x+x^2}{2x(1+x)}\) diverges as \(x\) approaches zero, but gets closer and closer to \(\frac{1}{2}\) as \(x=\frac{m}{2M}\) increases. This tells us that, as \(m\) increases compared to \(M\), Valentina’s speed ends up growing parallel to half of Mae’s speed.

In the specific case where Mae’s bowling ball is the same mass as her, \(M=m\), we find Mae is going \(20\%\) faster than Valentina.

Information: What is a rocket?

A rocket is not all that different to our astronauts and bowling balls: it’s a machine that pushes reaction mass out in order to make itself accelerate in the other direction.

Unlike the astronauts, the reaction mass comes out of a rocket in a steady stream rather than one or a few goes. Each tiny bit of reaction mass released must push all the reaction mass the rocket is still carrying. Nevertheless, we can analyse a rocket in a similar way to the way we analysed the astronauts.

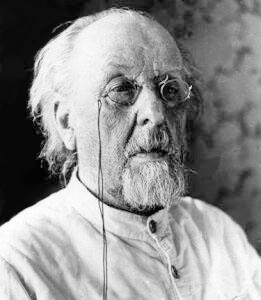

In 1897, long before any practical rockets had been created, the reclusive Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was busy imagining the future of human spaceflight in a log cabin near Kaluga.

He discovered a striking result: in a vacuum, the change in velocity produced by a rocket depends only on the speed of its exhaust, and the ratio of the mass of the rocket before it begins the burn, to the mass of the rocket after. He expressed this in a simple equation:

\[\Delta v=v_\text{e} \log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{after}}\]Let’s follow his work and find out what this equation means.

Aside: Relativistic rocket

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation is valid in Newtonian physics, which means it works when everything we’re dealing with is moving very slowly compared to the speed of light.

There is a relativistic version of the equation, and we need to use it instead of the Tsiolkovsky equation when we deal with very fast rockets using presently speculative technologies such as fusion torches or even antimatter propulsion.

The relativistic rocket equation looks like this for a rocket starting at zero speed:

\[v_\text{f} = c \tanh \left(\frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{after}}\right)\]For changes where the velocity does not start at zero, or adding up multiple rocket burns, we can most easily handle it using rapidity instead of velocity, since we can add up rapidity changes just like velocity changes. With rapidity coordinates, we have

\[\Delta w=\frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{after}}\]which is almost exactly like the Tsiolkovsky equation.

As we work out the rocket equation, these bonus boxes will illustrate how we’d do things differently for the relativistic rocket equation. If you haven’t learned about relativity yet, don’t worry - you can safely ignore them!

Question 3: Setting up the situation

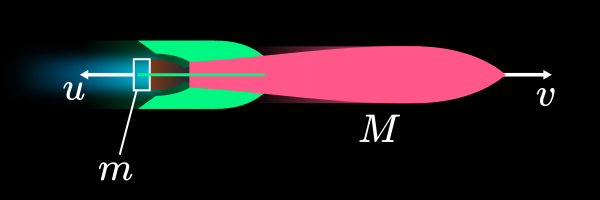

We will start our analysis in a frame of reference where the rocket has a total mass \(M\), and it is travelling at speed \(v\). Some exhaust of mass \(m\) is leaving the rocket at a velocity \(-u\).

We’re looking at this in a frame where the rocket’s travelling at speed \(v\). We know that in the rocket’s rest frame, the exhaust will be exiting the rocket with velocity \(-v_\text{e}\). What is the speed of the exhaust in this frame, \(u\)?

- \[u = v_\text{e} - v\]

- \[u = v - v_\text{e}\]

- \[u = v_\text{e} + v\]

Solution

We can transform into the rocket’s rest frame using the Galilean transformation.

The rocket’s rest frame is travelling at velocity \(+v\) relative to our frame. So, to get to the rest frame, we need to do a Galilean transformation with velocity \(-v\).

The rule for Galilean transformation of a velocity \(v\) by velocity \(V\) (in the same direction!) is that the velocity in the new frame, \(v'\), is given by

\[v' = v + V\]This can be straightforwardly applied to our case:

\[u = v_\text{e} - v\]Aside: Lorentz transforms and rapidity coordinates

In the relativistic case, transforming velocities between frames is more complicated. Instead of the Galilean transformation, we must use the Lorentz transformation.

The rule for a Lorentz transformation of a velocity \(v\) by a velocity \(V\) (in the same direction!) is that the velocity in the new frame, \(v'\), is given by

\[v' = \frac{v+V}{1+\frac{vV}{c^2}}\]In our case, that turns into

\[u = \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-\frac{vv_\text{e}}{c^2}}\]In a previous article, I’ve described how to derive the relativistic rocket equation using velocities like this. But the equation turns out to be somewhat clearer if we use rapidities instead of velocities directly.

In relativity, velocities of a massive object are always between \(-c\) and \(c\), but it can have unlimited amounts of kinetic energy or momentum. A small change in velocity near \(c\) causes a much bigger change in an object’s momentum and kinetic energy than when the velocity is near \(0\). As a metaphor, we can imagine the velocities have been ‘squashed up’.

A rapidity \(w\) is defined by an equation like \(\tanh w = \frac{v}{c}\). By using rapidities, we can imagine ‘stretching out’ the velocity over the full range between \(-\infty\) and \(+\infty\), in a way that makes them able to be added and subtracted directly, just like velocities.

Let’s define two rapidities: \(\tanh w = \frac{v}{c}\) and also \(\tanh r = \frac{u}{c}\). We also have the exhaust rapidity \(\tanh w_\text{e}=\frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\).

With rapidities, the velocity addition formula is greatly simplified. The formula for adding arguments of the hyperbolic tangent is

\[\tanh(x+y)=\frac{\tanh x + \tanh y}{1+ \tanh x \tanh y}\]which has the exact same form as the velocity addition formula. The result is that we can add rapidities together like velocities in Newtonian mechanics. Boosting by a rapidity \(W\) we get…

\[w'= w + W\]and in this case…

\[r = w_\text{e}- w\]Information: Differential of a function

There are a number of ways to derive the rocket equation, but here we’re going to do it in a way that can be easily paralleled by the relativistic case later, using the concept of a differential of a function.

The differential \(\dif f\) of a function \(f\) is a tool for describing a very small change in the value of a (smooth) function arising from a similarly small change in its variables - so small any nonlinear variation disappears.

We define the differential as

\[\dif f = \df{f}{x} \dif x\]for a function \(f(x)\) of a single variable, and

\[\dif f = \sum_{i=1}^n \pdf{f}{x_i}\dif x_i\]for a function \(f(x_1, \dots x_n)\) of multiple variables.

In other words, to get the differential, you add up the partial derivatives of the function with respect to each of its variables, each multiplied by the differential of the corresponding variable.

Aside: what is a differential?

We’ve defined a notation for differentials, but what exactly is it?

The notion of a differential goes back to Leibniz, one of the founders of calculus, created the \(\df{y}{x}\) and \(\int \dif x\) notation. To Leibniz, \(\dif x\) represented an infinitesimal quantity, smaller than any positive real number but greater than zero. A derivative such as \(\df{y}{x}\) was literally the ratio of two infinitesimal quantities, not just a convenient notation.

As mathematics developed, it became necessary to make calculus more rigorous. Although it was useful, it had been very unclear what, exactly, an infinitesimal quantity meant, so calculus was rebuilt in terms of a much more precise idea of a limit. This is the approach used in standard real analysis.

This made the notion of a differential seem rather suspect, but we can rebuild it in a number of ways. One straightforward approach is to see a differential \(\dif f\) as a function of two independent real variables \(x\) and \(\Delta x\), leading to expressions like:

\[\dif f (x, \Delta x) = f'(x) \Delta x\]and then, noting that \(\dif x (x, \Delta x) = \Delta x\) to recover the original

\[\dif f = f'(x)\dif x\]In this approach, the notion of the derivative of a function is fundamental, and differentials are a convenient tool we build on top of that.

More complicated treatments of differentials link it to other areas of mathematics, such as differential forms in differential geometry. You can read about them on Wikipedia’s article Differential (infinitesmial).

Question 4: Computing a differential

For a particular system of two particles whose masses can vary, the total momentum is given by

\[p(m_1,v_1,m_2,v_2)=m_1 v_1 + m_2 v_2\]What is the differential, \(\dif p\)?

- \[\dif p = m_1 \dif v_1 + m_2 \dif v_2\]

- \[\dif p = m_1 + v_1 + m_2 + v_2\]

- \[\dif p = m_1 \dif v_1 + v_1 \dif m_1 + m_2 \dif v_2 + v_2 \dif m_2\]

Solution

Using the above formula, the differential of \(p\) is written

\[\dif p = \pdf{p}{v_1}\dif v_1 + \pdf{p}{m_1} \dif m_1 + \pdf{p}{v_2} \dif v_2 + \pdf{p}{m_2} \dif m_2\]We evaluate the partial derivatives:

\[\begin{align} \pdf{p}{v_1}&=m_1 &\qquad \pdf{p}{m_1}&=v_1 \\ \pdf{p}{v_2}&=m_2 & \pdf{p}{m_2}&=v_2 \end{align}\]So we find

\[\dif p = m_1 \dif v_1 + v_1 \dif m_1 + m_2 \dif v_2 + v_2 \dif m_2\]Question 5: What does a rocket conserve?

If we know a physical quantity such as momentum is conserved, it gives us a constraint: we can change the variables that determine momentum (such as masses and velocities) in some ways, but not others. For the variables to change in a way that’s physically possible, the small, immediate changes in the momentum must cancel out to zero.

This means that conservation laws can be expressed by setting a differential to zero, such as

\[\dif p=0\]Which of the following quantities is not conserved in this stystem?

- total mass \(\mathcal{M}=m+M\)

- total momentum \(Mv - mu\)

- total kinetic energy \(\frac{1}{2}Mv^2 + \frac{1}{2}mu^2\)

Solution

No mass is entering or leaving the system, so the total mass \(\mathcal{M}=m+M\) is conserved.

No forces are acting on the system as a whole, so the total momentum \(p=Mv - mu\) is conserved.

However, potential energy in the rocket (e.g. chemical potential energy) is being converted into kinetic energy of the reaction mass, so the kinetic energy is not conserved.

Aside: relativistic conservation laws

In the relativistic case, there’s an interesting wrinkle: mass and energy are the same thing, and the potential energy stored in the rocket fuel is part of the mass of the rocket! That means the total mass is not conserved, since some of that mass turns into kinetic energy for the rocket and propellant.

Instead, we must conserve relativistic energy \(E=\gamma_v Mc^2 + \gamma_u mc^2\), where we’re introducing the gamma factor

\[\gamma_v=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}\]The relativistic momentum, \(p=\gamma_v Mv - \gamma_u mu\), is also conserved.

We’ll find it convenient to transform into rapidity coordinates now, since it will save us a bunch of algebra later. Let’s look at what happens if we place \(\tanh w = \frac{v}{c}\) in the relativistic \(\gamma\). We find:

\[\gamma_v = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\tanh^2 w}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\sech^2 w}}=\cosh w\]and

\[\frac{v}{c} \gamma_v = \tanh w \cosh w = \sinh w\]This means we can re-express the energy and momentum as:

\[\begin{align} E &= Mc^2 \cosh w + mc^2 \cosh r \\ p &= Mc \sinh w + mc \sinh r \end{align}\]Why are these conservation laws different? It is because in special relativity, the symmetry of space and time is different: we have Minkowski spacetime whose symmetry is the Poincaré group, instead of the more familiar Galilean group. This connection is due to a very fundamental principle called Noether’s theorem. In a later course, I hope to explain what that means.

Question 6: Conservation laws as differentials

Conserving the total mass gives us:

\[\dif \mathcal{M} = \dif M + \dif m = 0\]Conserving the total momentum gives us:

\[\dif p = v \dif M + M \dif v - m \dif u - u \dif m = 0\]We are considering the rocket to be increasing the mass \(m\) of propellant travelling at velocity \(-u\), rather than changing the velocity of the propellant already travelling at that velocity. So we say in the system we’re considering, \(u\) is a constant, i.e. \(\dif u=0\).

Combining these various results, what do we get?

- \[(v+u) \dif M + M \dif v=0\]

- \[(v-u) \dif M + M \dif v=0\]

- \[v \dif M + (M+u) \dif v = 0\]

Solution

Substituting \(\dif u = 0\) we find:

\[v \dif M + M \dif v - u \dif m = 0\]Then, substituting \(\dif M = - \dif m\) we find:

\[v \dif M + u \dif M + M \dif v = 0\]Grouping like terms:

\[(v+u) \dif M + M \dif v = 0\]Aside: differentials and relativity

As noted above, in the relativistic case, we can no longer rely on conservation of mass. Instead we set the differential of the total energy equal to zero:

\[\dif E = \dif (Mc^2 \cosh w) + \dif (m c^2 \cosh r) = 0\]And we set the differential of momentum equal to zero:

\[\dif p = \dif(Mc \sinh w) - \dif (m c \sinh r) =0\]The differentials come out as…

\[\begin{align} \dif E &= Mc^2 \sinh w \dif w + c^2 \cosh w \dif M + mc^2 \sinh r \dif r + c^2 \cosh r \dif m &= 0 \\ \dif p &= Mc \cosh w \dif w + c \sinh w \dif M - mc \cosh r \dif r - c \sinh r \dif m &= 0 \end{align}\]As in the Newtonian case, we’re going to say we’re only interested in changes with \(\dif r = 0\).

\[\begin{align} M \sinh w \dif w + \cosh w \dif M + \cosh r \dif m &= 0 \\ M \cosh w \dif w + \sinh w \dif M - \sinh r \dif m &= 0 \end{align}\]We would like to remove \(m\) from consideration, so let’s rearrange and divide (assuming \(r\ne 0\)):

\[\begin{align} \dif m &= -\sech r (M \sinh w \dif w + \cosh w \dif M) \\ &= \cosech r (M \cosh w \dif w + \sinh w \dif M) \end{align}\]Which means, in turn…

\[-\sinh r (M \sinh w \dif w + \cosh w \dif M) = \cosh r (M \cosh w \dif w + \sinh w \dif M)\]Bringing terms together…

\[M (\cosh r \cosh w + \sinh r \sinh w) \dif w + (\cosh r \sinh w + \sinh r \cosh w)\dif M\]We can now use some identities of hyperbolic functions:

\[\begin{align} \cosh(x+y)&=\cosh x \cosh y + \sinh x \sinh y \\ \sinh(x+y)&=\sinh x \cosh y + \cosh x \sinh y \end{align}\]So at last we get…

\[M \cosh (w+r) \dif w + \sinh(w+r)\dif M=0\]Amazingly, we can put this in a form almost exactly like the Newtonian case…

\[M\tanh(w+r)\dif M + \dif w = 0\]Question 7: Obtaining the rocket equation

We’re almost there. We just need to use the result we obtained earlier, expressing \(u\) in terms of the constant \(v_e\). We found \(u=v_\text{e}-v\), so that changes our expression to

\[v_\text{e}\dif M + M \dif v = 0\]This says, if we want to maintain conservation of momentum, any variations of \(v\) and \(M\) have to relate in this way. Let’s find a function \(v=v(M)\) that satisfies this condition.

We have a differential equation in only two variables, \(M\) and \(v\). We can rearrange it to separate variables:

\[\dif v = -v_\text{e} \frac{1}{M}\dif M\]We’ll integrate this with respect to \(M\), between limits \(M_\text{init}\) where \(v\) takes the value \(v_\text{init}\), and \(M_\text{final}\) where \(v\) takes the value \(v_\text{final}\):

\[\int_{v_\text{init}}^{v_\text{final}} \dif v = -v_\text{e} \int_{M_\text{init}}^{M_\text{final}}\frac{1}{M}\dif M\]What is the solution to this integral? (You can scroll up, but take the chance to solve it yourself!)

- \[v_\text{final}-v_\text{init} = v_\text{e} \log \frac{M_\text{final}}{M_\text{init}}\]

- \[v_\text{final}-v_\text{init} = v_\text{e} \log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{final}}\]

- \[v_\text{final}-v_\text{init} = v_\text{e} \left(\frac{1}{M_\text{init}^2}-\frac{1}{M_\text{final}^2}\right)\]

Solution

We’ll use the standard result that the integral of \(\frac{1}{x}\) over a domain with positive \(x\) is the natural logarithm of \(x\), i.e.

\[\int_{x>0} \frac{1}{x} \dif x = \log x + c\]With that in mind, we find

\[\begin{align}-\int_{M_\text{init}}^{M_\text{final}} \frac{1}{M}\dif M &= -(\log M_\text{final} - \log M_\text{init})\\ &=\log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{final}}\end{align}\]where we have used the identities that \(\log A + \log B = \log AB\) and \(-\log A = \log A^{-1}\) to simplify the result.

Aside: can you integrate a differential?

You may be wondering exactly how the notation for the differential of a function, e.g. \(\color{red}{\dif f}\), relates to the symbol used when integrating, e.g. \(\int x^2 \color{blue}{\dif x}\). Can we really just slap an integration sign on and call it a day?

Strictly speaking, as we’ve defined it, the delimiter \(\color{blue}{\dif x}\) used in integration has nothing inherently to do with the differential \(\color{red}{\dif f}\) of a function as we defined it above. However, nothing really goes wrong (at least in physics) if we treat it as the same as a differential, since when you deal with integration by substitution they behave the same way. Relying on intuition for the underlying maths, physicists often play fast and loose with the technicalities of concepts like differentials, often much to the frustration of mathematicians who have to clean up afterwards.

If we want to justify integrating the differential of a function, we can observe:

\[\color{red}{\dif f} = \df{f}{x} \color{red}{\dif x}\]is a valid differential; additionally, thanks to the fundamental theorem of calculus, when we integrate the first derivative of a (smooth, continuous) function

\[\int_a^b \df{f}{x}\color{blue}{\dif x} = f(b) - f(a)\]it will give us the same thing as

\[\int_{f(a)}^{f(b)} \color{blue}{\dif f}= f(b) - f(a)\]It would be a pain and more confusing than clear to write all that out every time, so in physics we generally talk about integrating differentials directly.

To make these ideas more rigorous, we could look to the idea of differential 1-forms in differential geometry, but that’s way too heavy-duty for the problems we’re dealing with here.

Aside: obtaining the relativistic rocket equation

We just found

\[\tanh(w+r)\dif M + M \dif w =0\]And we found earlier that, expressed in rapidity terms, the Lorentz transform says

\[r = w_\text{e}- w\]Which means \(\tanh(w+r)=\tanh(w_\text{e})=\frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\) and we get an identical equation to the Newtonian case, except expressed in terms of \(w\) instead of \(v\)!

\[\dif w=-\frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\frac{1}{M}\dif M\]This is the same differential equation, so it has the same solution:

\[w_\text{final} - w_\text{init} = \frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{final}}\]In the case that the rocket starts at zero speed, so \(v_\text{init}=w_\text{init}=0\), we can get a simple expression for \(v_\text{final}\):

\[v_\text{final} = c \tanh w_\text{final} = c \tanh \left(\frac{v_\text{e}}{c}\log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{final}}\right)\]Information: A little terminology…

Hooray, we’ve derived the rocket equation! Let’s see it again::

\[\Delta v = v_\text{e} \log \frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{final}}\]Here, the difference of velocities \(v_\text{final}-v_\text{init}\) is written \(\Delta v\), pronounced ‘delta-vee’.

Mission planners think of it this way: a rocket has a ‘total budget’ of delta-v when it launches, and each time it turns on its engines and performs a maneuver to change its velocity in some way, it uses up some of its delta-v. To get to any particular place in the solar system (or beyond), there’s a minimum delta-v ‘cost’. So a mission must balance its delta-v ‘budget’ against the ‘cost’ of getting where it needs to go.

The exhaust velocity \(v_\text{e}\) is also commonly called the specific impulse, \(I_\text{sp}\). This is because you can calculate the effective exhaust velocity of a rocket by dividing the thrust by the rate that mass leaves the engine. ‘Specific’ is commonly used as a word meaning ‘per unit mass’, so specific impulse is also a measure of ‘force per unit mass propellant per second’.

A wrinkle: specific impulse in seconds

There’s a confusing wrinkle here, because there’s another, related measure that’s also called the specific impulse that’s measured as a time instead of a force. The specific impulse as a time is obtained by dividing the specific impulse as a speed by the standard gravity \(g_0=9.81\unit{ms^{-2}}\).

Presented like this, writing the specific impulse in seconds seems completely ridiculous. The reason is that, historically, quantities of fuel would be measured by weight (at the surface of the Earth) instead of mass. So, scientists thought of the ‘weight flow rate’ instead of the ‘mass flow rate’. When you divide the thrust by the rate that weight leaves the engine, you get a time, not a speed.

Specific impulses are, unfortunately, often still reported in seconds because it’s hard to break from tradition. For example, if we look up the Saturn V rocket, we find the specific impulse of its first stage is \(263\unit{s}\). To actually use this in a calculation, we have to turn it back into a speed by multiplying this value by \(g_0\), which turns out to be \(263\unit{s}\times9.81\unit{ms^{-2}}=2.58\unit{kms^{-1}}\).

The ratio \(\frac{M_\text{init}}{M_\text{final}}\) is called the rocket’s mass ratio. (Some authors, such as Sutton and Biblarz in Rocket Propulsion Elements, use the term ‘mass ratio’ for the inverse of this, \(\frac{M_\text{final}}{M_\text{init}}\).)

The rocket equation tells us there are only two ways to get more delta-v: increase the mass ratio (i.e. carry a greater proportion of the rocket’s mass as propellant) or use an engine with a higher specific impulse.

Question 8: Does thrust matter?

We mentioned another measure to describe a rocket engine: the thrust, which is the force applied by the engine. The thrust and mass of the rocket together determine how quickly a rocket accelerates. But, curiously, it’s nowhere to be seen in the rocket equation. Let’s have a look at what that means.

Suppose two rockets launch, with zero velocity, at the same time. Each rocket has the same mass and amount of propellant. The rockets each have a hundred engines, but on one of the two rockets, there is a malfunction and only one of the engines starts. Both rockets burn through all of their propellant.

Do the rockets reach the same velocity? (Ignore any effects of torque from off-centre thrust.)

- Yes

- No

Solution

Both rockets have the same initial mass, and same final mass. So they will reach the same velocity. The fact that one rocket has a hundred times the thrust of the other doesn’t matter at all! (Of course, the rocket with a hundred engines will reach its final speed much, much more quickly than the broken rocket.)

Question 9: Using the rocket equation directly

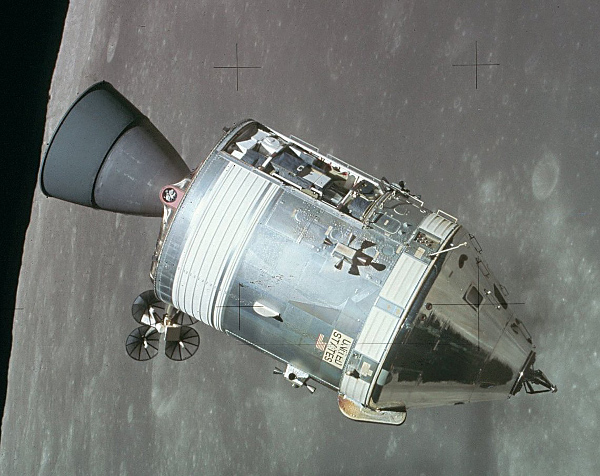

In December 1968, the Apollo 8 mission carried three people to orbit the Moon for the first time in history. The final stage of the mission was the Command/Service Module. After the Saturn V’s SIV-B stage put it on a translunar orbit, the Command/Service Module inserted the astronauts into lunar orbit, and then back out of orbit to return to Earth.

The Command/Service Module had a launch mass of \(28\,800\unit{kg}\), and a dry mass (i.e., mass when its propellant had all been expelled) of \(11\,900\unit{kg}\). The Service Module’s AJ10-137 engine had a specific impulse of \(3.13\unit{kms^{-1}}\).

What was the total \(\Delta v\) available to the Command/Service Module?

Solution

Applying the rocket equation, we find

\[\Delta v = 3.13 \unit{kms^{-1}} \cdot \log \left(\frac{28\,800\unit{kg}}{11\,900\unit{kg}}\right)=2.77\unit{kms^{-1}}\]Question 10: Using the rocket equation in reverse

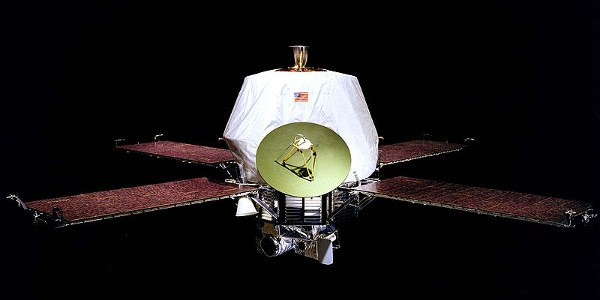

You’re tasked with designing a space probe designed to orbit Mars and send back information.

After the launch rocket releases your probe in Low Earth Orbit, you’ve looked up that it will take \(4.3\unit{kms^{-1}}\) to transfer to a Mars transfer orbit, \(0.9\unit{kms^{-1}}\) to enter Mars capture orbit instead of flying by, and \(\unit{1.4\unit{kms^{-1}}}\) to go from the wildly elliptical capture orbit to the desired low Mars orbit.

Adding it all up, the mission requires a total \(\Delta v\) of \(6.6\unit{kms^{-1}}\).

The probe’s instruments and structure have ended up massing \(500\unit{kg}\). The probe has a chemical rocket with a specific impulse of \(3\unit{kms^{-1}}\). What is the minimum mass of propellant the probe needs to complete its mission?

Answer to the nearest \(100\unit{kg}\).

Solution

We know that the probe’s final mass once it’s burned its propellent is \(M_\text{final}=500\unit{kg}\). The rest of the rocket’s mass is propellant, so the propellant mass is \(M_\text{init}-M_\text{final}\).

We will rearrange the rocket equation to calculate \(M_\text{init}\).

\[M_\text{init}=M_\text{final}\exp \left(\frac{\Delta v}{v_\text{e}} \right)\]Substituting in our quantities, we find:

\[M_\text{init}=500\unit{kg} \cdot \exp \left( \frac{6.6\unit{kms^{-1}}}{3\unit{kms^{-1}}}\right)=4500\unit{kg}\]From this we can subtract the \(500\unit{kg}\) of the probe itself, so the propellant mass is \(4000\unit{kg}\).

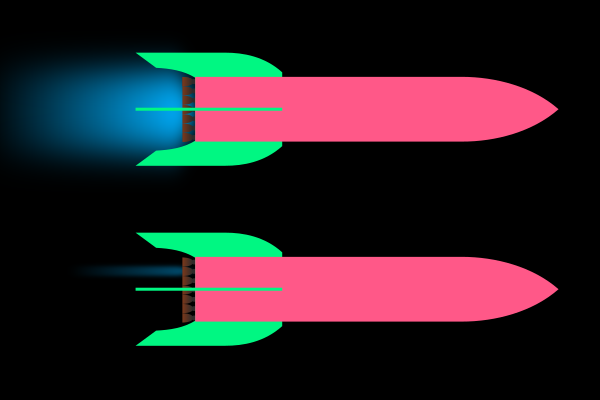

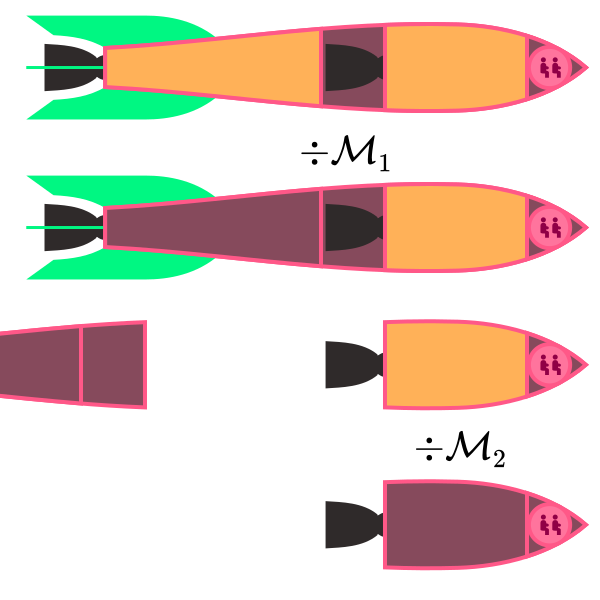

Information: Staging

Often, a big part of the mass of the rocket is fuel tanks, and the more fuel you have, the more tank you need. But while spent fuel is no longer slowing down the rocket, the empty tank remains.

For this reason, rockets are often designed in stages. Instead of one big fuel tank, they have several fuel tanks, and several engines. Each stage will exhaust its fuel, and then discard the heavy tanks and engine.

To see the effect of staging, suppose you have two stages. Their mass ratios are \(\mathcal{M}_1\) and \(\mathcal{M}_2\). Both stages have the same exhaust velocity \(v_\text{e}\). (Note that \(\mathcal{M}_1\) includes the mass of the second stage in both \(M_\text{init}\) and \(M_\text{final}\)!)

We calculate the total delta-v by adding together the delta-vs of each stage.

\[\begin{align} \Delta v &= v_\text{e} \log \mathcal{M}_1 + v_\text{e} \log \mathcal{M}_2\\ &= v_\text{e} \log \mathcal{M}_1 \mathcal{M}_2 \end{align}\]So it’s the same as if the rocket had one stage, whose mass ratio is the product of mass ratios of each stage! This applies if you have many stages too, as long as every stage has the same specific impulse. The result is that staging can win back a lot of delta-v.

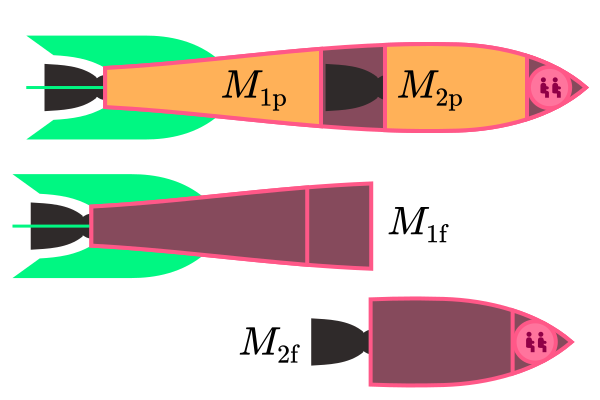

Aside: Staging in detail

Above, we kind of glossed over that each stage includes all its future stages. Let’s include that explicitly in the calculation and see where it gets us.

Suppose there is a rocket that has two stages. The first stage has a dry mass of \(M_{1\text{f}}\), and a mass of propellant \(M_{1\text{p}}\). The second stage has a dry mass of \(M_{2\text{f}}\), and a mass of propellant \(M_{2\text{p}}\). Both stages have the same exhaust velocity \(v_\text{e}\).

Let’s first consider the case where the two segments stay attached. The launch mass of the full rocket is

\[M_{1\text{f}}+M_{1\text{p}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}\]and the final mass is

\[M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}}\]so, with the rocket equation, the rocket’s delta-v is

\[\Delta v = v_\text{e} \log \left( \frac{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{1\text{p}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}}}\right)\]Now, suppose that after the first stage has finished burning, it is jettisoned.

The first stage now produces a \(\Delta v\) of

\[\Delta v_1 = v_\text{e} \log \left( \frac{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{1\text{p}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}\right)\]The second stage produces a \(\Delta v\) of

\[\Delta v_2 = v_\text{e} \log \left( \frac{M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{2\text{f}}}\right)\]So the total \(\Delta v\) is…

\[\begin{align} \Delta v_\text{tot} &= \Delta v_1 + \Delta v_2 \\ &= v_\text{e} \left(\log \left( \frac{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{1\text{p}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}\right)+\log \left( \frac{M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{2\text{f}}}\right)\right)\\ &= v_\text{e} \log \left(\frac{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{1\text{p}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}\cdot\frac{M_{2\text{f}}+M_{2\text{p}}}{M_{2\text{f}}}\right) \end{align}\]Phew, that’s ugly! But now we can ask: how much more delta-v do we get by using a staged rocket?

Unfortunately, with a complicated polynomial fraction in four different variables, we can’t get very far.

To simplify things, let’s assume we’re dealing with a particular rocket where each stage has \(f\) times as much propellant as structural mass, i.e.

\[\begin{align} M_{1\text{p}}&=fM_{1\text{f}}\\ M_{2\text{p}}&=fM_{2\text{f}} \end{align}\]In other words, each stage on its own has a mass ratio \((1+f)\); this is also the mass ratio of the unstaged version.

Now, the \(\Delta v\) becomes…

\[\begin{align} \Delta v &= v_\text{e} \log \left(\frac{(1+f)^2(M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}})}{M_{1\text{f}}+(1+f)M_{2\text{f}}} \right)\\ &=v_\text{e}\log(1+f) + v_\text{e}\log\left(\frac{(1+f)(M_{1\text{f}}+M_{2\text{f}})}{M_{1\text{f}}+(1+f)M_{2\text{f}}} \right)\\ &=v_\text{e}\log(1+f) + v_\text{e}\log\left(1+\frac{f}{1+(1+f)\frac{M_{2\text{f}}}{M_{1\text{f}}}} \right) \end{align}\]That’s still not pretty, but we can at least see that we are definitely going to get more delta-v. Also, we can see that - at least in this case - it helps to have the first stage be larger than the second.

You could play around with this kind of equation in all kinds of ways, but we’ll leave that to revisit at another time perhaps…

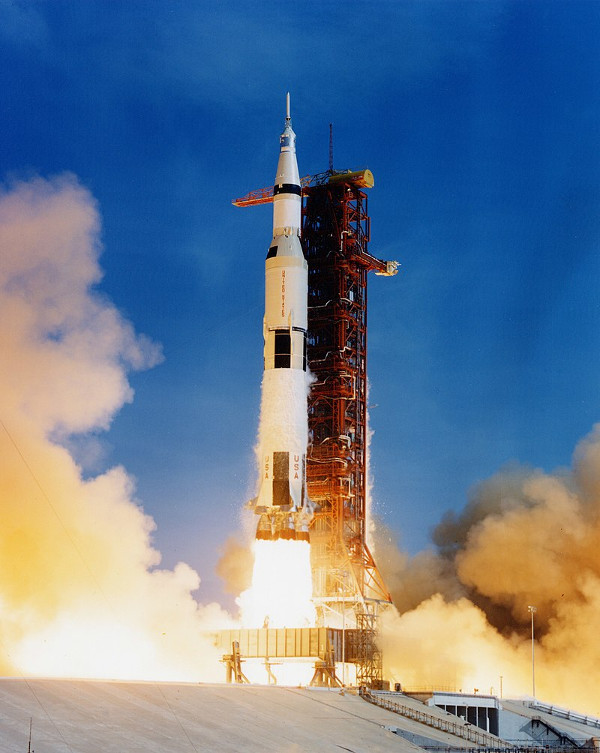

Challenge question: the Saturn V

We’ve covered a lot of ground to get this far. For a final, challenge question, let’s see if we can deal with one of the most famous rockets in spaceflight history: the Saturn V rocket that took humans to the Moon. Can we work out its total delta-v?

The Apollo Saturn V stack consists of the following components:

- first stage: S-IC. Masses \(130\,000\unit{kg}\) empty, and \(2\,290\,000\unit{kg}\) full. Exhaust velocity: \(2.58\unit{kms^{-1}}\) (at sea level).

- second stage: S-II. Masses \(40\,100\unit{kg}\) empty (including the S-II/S-IVB interchange), and \(496\,200\unit{kg}\) full. Exhaust velocity: \(4.13\unit{kms^{-1}}\) (in vacuum).

- third stage: S-IVB. Masses \(13,500\unit{kg}\) empty (including the instrument unit), and \(123\,000\unit{kg}\) full. Exhaust velocity: \(4.13\unit{kms^{-1}}\) (in vacuum).

- Command and Service Module: masses \(11\,900\unit{kg}\) empty, and \(28\,800\unit{kg}\) full. Exhaust velocity: \(3.13\unit{kms^{-1}}\).

On all the missions after Apollo 8, there was also a Lunar Module, which flew with the Command and Service Module until the moon. However, because it is difficult to work out exactly how much delta-v is spent before the Lunar Module is jettisoned, let’s analyse the Apollo 8 mission, which did not carry a Lunar Module. Instead, Apollo 8 carried…

- a Lunar Test Article, massing \(9\,000\unit{kg}\), which was jettisoned along with the third stage.

What is the total delta-v available to Apollo 8?

Solution

We proceed as follows:

- calculate the mass of the Apollo stack at various points in the mission

- use this to calculate the delta-v of each stage

- add these delta-vs together.

The points we will consider are:

- the rocket at launch

- when the first stage is empty, just before separation

- after first stage separation

- when the second stage is empty, just before separation

- after second stage separation

- when the third stage is empty, just before separation (this is where transposition and docking would occur on a full mission)

- the Command and Service module, full

- the Command and Service module, empty

We can work backwards through this list:

- CSM (empty): \(11\,900\unit{kg}\)

- CSM (full): \(28\,800\unit{kg}\)

- S-IVB (empty) + LTA + CSM (full): \(51\,300\unit{kg}\)

- S-IVB (full) + LTA + CSM (full): \(160\,800\unit{kg}\)

- S-II (empty) + S-IVB (full) + LTA + CSM (full): \(200\,900\unit{kg}\)

- S-II (full) + S-IVB (full) + LTA + CSM (full): \(657\,000\unit{kg}\)

- S-IC (empty) + S-II (full) + S-IVB (full) + LTA + CSM (full): \(797\,000\unit{kg}\)

- full Apollo 8 rocket: \(2\,947\,000\unit{kg}\)

With these, we can calculate the delta-v produced in each set of burns:

- S-IC: \(\Delta v = 2.58\unit{kms^{-1}} \cdot \log \frac{2\,947\,000}{797\,000}=3.37\unit{kms^{-1}}\)

- S-II: \(\Delta v = 4.13\unit{kms^{-1}} \cdot \log \frac{657\,000}{200\,900}=4.89\unit{kms^{-1}}\)

- S-IVB: \(\Delta v = 4.13\unit{kms^{-1}} \cdot \log \frac{160\,800}{51\,300}=4.71\unit{kms^{-1}}\)

- CSM: \(\Delta v = 3.13\unit{kms^{-1}} \cdot \log \frac{28\,800}{11\,900}=2.76\unit{kms^{-1}}\)

Now, we add them all up to get a total delta-v of \(15.73\unit{kms^{-1}}\)

Unfortunately, it is difficult to find a place where NASA has calculated the same figure. Instead, let’s compare it to the delta-v requirements of a Moon mission. According to Wikipedia’s delta-v table, to get from Earth’s surface to low Earth orbit, we need about \(10\unit{kms^{-1}}\), and from there to get to a low Lunar orbit we need another \(4.04\unit{kms^{-1}}\). To return to a low Earth orbit from there takes a final \(1.31\unit{kms^{-1}}\). (The remainder of our energy will be dumped into the atmosphere by aerobraking.)

The total requirements for the mission add up to \(15.35\unit{kms^{-1}}\). So we are extremely close!

The real mission of course differed from this calculation for a few reasons…

- NASA engineers include some extra fuel for course corrections and dealing with emergencies. In the case of the Apollo 13 mission, this proved crucial for returning the astronauts alive.

- the performance of the Saturn V engines varied as the rocket travelled through the atmosphere. The first and second stages were designed to work best in an atmosphere, while the third stage and the CSM were designed to work best in a vacuum. The rockets’ specific impulse changed as the Saturn V gained altitude.

- while flying through the atmosphere, the Saturn V was subject to atmospheric drag which drained away some of its speed.

Conclusions

We have learned:

- how to calculate the differential of a function

- how to express laws like conservation of momentum using a differential

- how to use this differential formulation to derive the Rocket Equation

- how to use the Rocket Equation to plan space missions

- how to understand parameters of a rocket like specific impulse and mass ratio

To get a really good, intuitive feel for these principles, nothing beats playing with a rocket simulator.

- the game Kerbal Space Program simplifies the physics enough to make it managable if you’re not already an expert, and allows you to build an enormous variety of spacecraft from components with a flexible builder system. And if that gets too easy, try mods such as Realism Overhaul…

- the simulator Orbiter is much more realism-orientated, and free (though not open source). It can be extended using community add-ons for a similar variety of spacecraft.

Comments