originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/979547...

Let’s suppose you urgently need to reach another star system. And generation ships and suspended animation aren’t an option.

In this post, we’ll work out some relevant maths to help you get there. This post covers the relativistic rocket equation, $$ v_\text{f} = c \tanh \left( \frac{v_\text{e}}{c} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)$$

To see what’s different about it, we’ll work it out alongside the somewhat better known, Newtonian Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, $$\Delta v = v_\text{e} \ln \frac {M_\mathrm{i}} {M_\mathrm{f}}$$

I’m going to try to cover the basics of Newtonian mechanics and special relativity needed for the derivations. The derivation itself uses a bit of calculus (differentials of functions, product rule and chain rule, integration of 1/x) and some logarithms, but nothing beyond A-level. Hopefully I’ve included enough that you can get something out of this post even if you stop at the maths-heavy bit! The next post, using this equation to work out a space mission to another star, should be a bit more accessible.

So when you’re in space, if you don’t do anything, you’re going to keep moving. If there’s no other matter around, you will fly in a straight line; if there is something nearby, you will be attracted to it by gravity (in general, your course is a geodesic of the spacetime geometry you find yourself in).

To change your course from whatever path you’re flying along, there are basically two things you can do…

One thing you can do is split yourself in two, and throw part of you away. You will be propelled directly away from the bit of you that you discarded. This is how a rocket works: the rocket propels reaction mass away from it, adding a component to its velocity in the opposite direction. Of course, there is a limit to this: at some point, there will be nothing left of you to throw away.

The other thing you can do is bump into something. This something could be a rock, or just light (which carries momentum!). This depends on the availability of stuff going in the right direction you can bounce off. So it helps to have someone behind you with e.g. a massive laser, but you can also just use sunlight if you’re going in the right direction.

OK, preamble out the way. The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation is a famous equation that describes how a Newtonian rocket changes its velocity as a function of the exhaust velocity (also known as specific impulse) and the amount of mass that’s launched away (expressed the mass ratio).

If the mass you start with is \(M_\mathrm{i}\) and the mass that remains after your rocket burn is \(M_\mathrm{f}\), and your exhaust speed is \(v_\text{e}\), then the amount your velocity changes (your delta-V) is

$$\Delta v = v_\text{e} \ln \frac {M_\mathrm{i}} {M_\mathrm{f}}$$

That’s all well and good - we’ll get on to how it’s derived in a second. But that only applies in a Newtonian universe. Now, every theory in physics is an approximation with a limited range of applicability. And very fast spaceships (i.e. more than about \(0.2c\)) is one of the situations in which Newtonian physics increasingly gets stuff wrong.

To emphasise, that’s really very fast. The fastest ever human-made object was apparently NASA's Juno spacecraft shortly before its insertion burn at Jupiter, at which point it was travelling at \(74\unit{km\,s^{-1}}\), which is 'only' \(0.00025c\). Juno achieved this speed (slightly faster than earlier solar probes) by a series of gravitational assist maneuvres, stealing momentum from the planets in a complicated course.

OK, so without Newtonian mechanics, what do we use? I guess the “Newton has failed me!” algorithm goes simething like this:

- if something’s going really fast and you’re a safe distance from anything really heavy, you need special relativity

- if you are dealing with something incredibly heavy like a neutron star or a black hole or the entire universe, you need general relativity

- if you’re dealing with incredibly tiny or incredibly cold things, you need quantum mechanics

(of course there’s a whole lot more than that, but more or less…)

In this case, all we need is special relativity.

What’s that? What difference does it make to rockets?

The differences between Newtonian physics and special relativity can be basically seen in what happens when two people (in general, any objects) are travelling past each other at a constant speed.

In Newtonian physics, there’s one system of time, and everyone agrees about how fast time is going and whether or not things in different places are simultaneous, and whether lengths are the same. Anyone can travel at any speed relative to anyone else. On the other hand, observers moving relative to each other always observe other objects moving at different speeds relative to themselves, no matter how fast that object is going.

In special relativity, time passes at a different rate for every observer, and two things which appear to be simultaneous for one observer will look like they’re happening at different times to someone travelling relative to them, and lengths will seem different to each observer. (All of this is captured succinctly in the Lorentz transformation of four-dimensional space).

On the other hand, there is something everyone can agree on: no matter how fast someone is travelling, there’s one speed, \(c\), that seems the same to every observer. Light travels at that speed, so we call it the ‘speed of light’. Nobody can transmit information or travel faster than \(c\) without causing all kinds of paradoxes.

Fortunately, it turns out that when everything’s slow compared to \(c\), Newtonian physics is an incredibly good approximation to special relativity, which is why we never noticed anything wrong with it for several hundred years.

Tell me about rockets now please? You said this blog post was about rockets!

Before we can talk about rockets, we need to introduce another difference between special relativity and Newtonian mechanics: the kind of momentum that gets conserved.

For every object in a system of interacting objects, you can calculate a vector quantity called the momentum, \(\mathbf{p} = m \mathbf{v}\) (for an object of mass \(m\) travelling at velocity \(\mathbf{v}\)). You can add up all these vectors to get a quantity of the entire system called the total momentum.

Conservation of momentum is the property that the system only evolves in ways that don’t change the total momentum.

The 'reason’ for this is actually to do with the 'continuous displacement symmetry’ of the system, which means you can move the entire system in the same way by an arbitarily small amount, and it won’t change the way the system evolves. If and only if that’s true, momentum will be conserved. This is an instance of a famous theorem by my favourite mathematician, Emmy Noether.

(What is conserved is not necessarily \(\mathbf{p} = m \mathbf{v}\), but in general a canonical momentum of the system. But that’s a big post in itself, so I’ll save talking about Noether’s Theorem for now…)

Special relativity has a different group of symmetries than Newtonian physics, and so a different Lagrangian, and because of that, the 'momentum’ that the system has from displacement-symmetry is not \(\mathbf{p} = m \mathbf{v}\), but $$\mathbf{p} = \frac{m \mathbf{v}}{\sqrt{1 - \left(\frac{v}{c}\right)^2}}$$

(Here \(m\) is always the rest mass of the object, we’re not using any concept of “relativistic mass” here.)

For the sake of making things a bit clearer/followable, we’re going to do a thing that’s common in relativity calculations, and use a system of ’natural units’ in which \(c=1\). (This means that time and distance have the same dimension in these units! Yes it’s weird, but it’s legit. Really. At the end, we can put the factors of \(c\) back in.)

If we do this, instead our conserved momentum is $$\mathbf{p} = \frac{m \mathbf{v}}{\sqrt{1 - v^2}}$$ It’s convenient to define $$\gamma_v = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-v^2}}$$ Then we have \(\mathbf{p} = \gamma_v m \mathbf{v}\).

Momentum is not the only conserved quantity. In Newtonian mechanics, the total mass of all the objects is conserved.

In special relativity, things are more complicated. Rest mass of objects can be transformed into other forms of energy, and you have to take both into account. The total energy of a moving object is \(E=\gamma_v m\). (Remember \(c=1\)! You have to put \(c^2\) back in if you’re not using natural units so this is the general form of \(E=m c^2\)).

ROCKETS OK?

Right. Rockets it is. Let’s derive the rocket equation, in both the relativistic form and the Newtonian form side-by-side.

I’m kind of inspired by an educational paper that does just that, but with old-school pre-\(\mathrm{\LaTeX}\) typesetting and choices of notation that don’t fit how I like to do things (i.e., using 'relativistic mass’ instead of 'relativistic momentum’). I’m also relying on this forum post which outlines a derivation without relativistic mass.

That said, both those sources leave out steps, so I’m filling in a lot of the gaps as I write this post! I’ve also made some changes. I’m working directly into Tumblr, so here and there you’ll see some of the process I go through trying to work out this kind of problem.

Our illustration rocket will be powered by the highly sophisticated Arm Drive, which is where the pilot picks up extremely small bowling balls and hurls them out the back of her spaceship. As far as the astronaut is concerned, the bowling ball leaves the rocket at a speed \(v_\text{e}\).

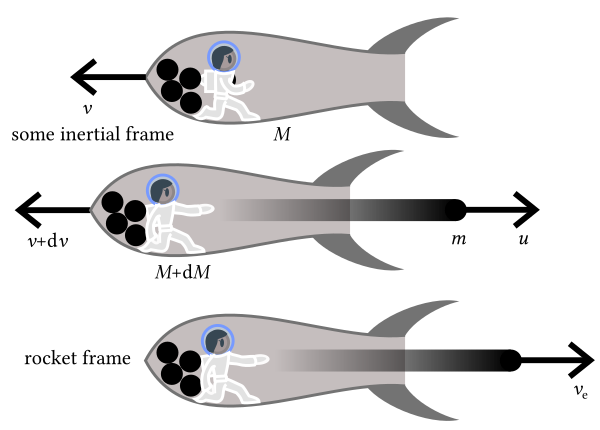

Let’s start, as in the top picture, in an inertial frame of reference where the ship has velocity \(v\), and starts with mass \(M\).

To start with, our ship has rest mass \(M\). After the astronaut hurls a bowling ball of rest mass \(\mathrm{d}m\) out the back at velocity \(-u\), the ship’s mass and velocity change small amounts \(\mathrm{d}M\) and \(\mathrm{d}v\).

Now we conserve momentum in this frame. We only have one dimension here, so we have…

- Newtonian case: $$Mv = Mv+ \mathrm{d} (Mv) - u\mathrm{d}m$$

- Relativistic case: $$\gamma_v M v = \gamma_v M v + \mathrm{d} (\gamma_v M v) - \gamma_u u\mathrm{d}m$$

These can be simplified and expanded with the product rule:

- Newtonian case: $$v \mathrm{d} M + M \mathrm{d} v - u\mathrm{d}m = 0$$

- Relativistic case: $$\gamma_v v \mathrm{d} M + M \mathrm{d}(\gamma_v v) - \gamma_u u \mathrm{d}m = 0$$

We can find \(u\) in terms of \(v_\text{e}\) (that is, the speed the bowling ball is travelling in the rocket’s rest frame) with a Galilean transformation (Newtonian case) or Lorentz transformation (relativistic case).

- Newtonian case: $$u=v_\text{e} - v$$

- Relativistic case: $$u= \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v}$$

In the Newtonian case, mass is conserved. Total kinetic energy isn’t conserved, because extra energy is coming in from burning the fuel, and in Newtonian physics, that energy doesn’t contribute mass to the rocket.

In the relativistic case, the energy used by the fuel to accelerate the rocket forms part of the total mass of the ship, so we don’t conserve rest mass, but do conserve energy.

Applying these laws and simplifying much as before…

- Newtonian case: (mass conserved) $$\mathrm{d}M=-\mathrm{d}m$$

- Relativistic case: (energy conserved) $$\mathrm{d} (\gamma_v M) = - \gamma_u \mathrm{d}m$$

Next, we need to combine these three conservation laws into one expression.

First, we substitute the result we got from mass/energy conservation into the results of momentum conservation.

- Newtonian case: $$v \mathrm{d} M + M \mathrm{d} v + u\mathrm{d}M = 0$$

- Relativistic case: $$\gamma_v v \mathrm{d} M + M \mathrm{d}(\gamma_v v) + u \mathrm{d} (\gamma_v M) = 0$$

Next, we swap out \(u\) for the appropriate function of \(v\) and \(v_\text{e}\).

- Newtonian case: $$v \mathrm{d} M + M \mathrm{d} v + (v_\text{e} - v)\mathrm{d}M = 0$$

- Relativistic case: $$\gamma_v v \mathrm{d} M + M \mathrm{d}(\gamma_v v) + \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \mathrm{d} (\gamma_v M) = 0$$

We now want to simplify the equation to group the terms in \(\mathrm{d}v\) and \(\mathrm{d}M\), so we can express a nice simple first-order differential equation \(\frac{\mathrm{d}v}{\mathrm{d}M} = \text{something}\). If we’re lucky, it will turn out to be separable, i.e. \(f(M)\mathrm{d}M=g(v)\mathrm{d}v\), in which case we can solve it easily by integration. Let’s find out.

The Newtonian side is easy: we have

- Newtonian case: $$\frac{\mathrm{d}v}{v_\text{e}}= -\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M}$$

The relativistic side can also be brought into a separable form, but it takes some more work. I’m going to try doing it without using 'rapidity’ coordinates to maintain parallels.

The first step on the relativistic side is to expand the derivatives of \(\gamma_v\). Applying the chain rule, we have $$\mathrm{d} \gamma_v = \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d} v} \left( (1 - v^2)^{-\frac{1}{2}} \right) \mathrm{d}v= v{(1-v^2)}^{-\frac{3}{2}}\mathrm{d}v=\frac{v}{1-v^2}\gamma_v \mathrm{d}v $$

By the product rule, $$\mathrm{d}(\gamma_v v) = \gamma_v \left(1+ \frac{v^2}{1-v^2}\right)\mathrm{d}v = \gamma_v (1-v^2)^{-1}\mathrm{d}v$$

And, similarly, $$\mathrm{d}(\gamma_v M) = \gamma_v \mathrm{d}M + \frac{Mv}{1-v^2}\gamma_v \mathrm{d}v$$

Substituting all of this back in, we find

- Relativistic case: $$\gamma_v v \mathrm{d} M + M \gamma_v (1-v^2)^{-1}\mathrm{d}v + \gamma_v \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \left( \mathrm{d}M + \frac{Mv}{1-v^2} \mathrm{d}v \right) = 0$$

Conveniently, we can now divide out a factor of \(\gamma_v M\), producing

- Relativistic case: $$v \frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} + (1-v^2)^{-1}\mathrm{d}v + \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \left( \frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} + \frac{v}{1-v^2} \mathrm{d}v \right) = 0$$

Grouping terms in \(\mathrm{d}v\) and \(\mathrm{d}M\), this becomes

- Relativistic case: $$\left(v + \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \right)\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} + \left(1+ v\frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \right) \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{1-v^2} = 0$$

The term on the right can be simplified using $$\left(1+ v\frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \right) = \frac{1-v^2}{1-v_\text{e}v}$$

This gives

- Relativistic case: $$\left(v + \frac{v_\text{e}-v}{1-v_\text{e} v} \right)\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} + \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{1-v_\text{e} v} = 0$$

Now, multiplying through by \(1-v_\text{e} v\), things cancel out beautifully and we’re left with

- Relativistic case: $$v_\text{e}(1-v^2)\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} + \mathrm{d}v = 0$$

So, bringing back our earlier result for the Newtonian side, our two differential equations are

- Newtonian case: $$\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M}= -\frac{\mathrm{d}v}{v_\text{e}}$$

- Relativistic case: $$\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} = - \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{v_\text{e}(1-v^2)}$$

I just want to pause here and point out how beautiful these equations are. You see that? Wow.

OK.

The next thing we do is integrate these differential equations, from an initial state, in which our rocket has mass \(M_\mathrm{i}\) and velocity \(v_\text{i}\), to the final state, when our rocket has mass \(M_\mathrm{f}\) and velocity \(v_\text{f}\). So we have

- Newtonian case: $$\int_{M_\mathrm{i}}^{M_\mathrm{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} = -\frac{1}{v_\text{e}}\int_{v_\text{i}}^{v_\text{f}} dv$$

- Relativistic case: $$\int_{M_\mathrm{i}}^{M_\mathrm{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M} = -\frac{1}{v_\text{e}}\int_{v_\text{i}}^{v_\text{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{1-v^2}$$

The integral on the left hand side, \(\int_{M_\mathrm{i}}^{M_\mathrm{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M}\), is a common one that gives us logarithms. We just get $$\int_{M_\mathrm{i}}^{M_\mathrm{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}M}{M}=\ln M_\mathrm{f} - \ln M_\mathrm{i}=\ln \frac{M_\mathrm{f}}{M_\mathrm{i}}$$

In the Newtonian case, the right hand side is also straightforward. So we have

- Newtonian case: $$- v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_f}{M_i} = v_\text{f} - v_\text{i}$$

Bringing the - sign inside the logarithm, and defining \(\Delta v = v_\text{f} - v_\text{i}\), this finally becomes the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation.

- Newtonian case: $$\Delta v = v_\text{e} \ln \frac {M_\mathrm{i}} {M_\mathrm{f}}$$

OK, but what about the relativistic case? The right hand side here is maybe a bit less familiar. We can look up the integral in a table of standard integrals of course, but let’s see if we can work it out using our usual tools (no, not Mathematica!).

The problem is the quadratic denominator \(1-v^2\).

The first thing I notice that you can factorise it to \((1-v)(1+v)\). That suggests partial fractions: we want to turn this fraction into some kind of form like $$\frac{A}{1-v}+\frac{B}{1+v}$$ For this to be true, we need to have $$A(1+v)+B(1-v)=1$$ for all \(v\). Rearranging, we have $$(A+B)1 + (A-B)v=1+0v$$so \(A+B=1\) and \(A-B=0\). This is solved by \(A=B=\frac{1}{2}\).

So we have \begin{eqnarray}\int_{v_\text{i}}^{v_\text{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{1-v^2} & = & \frac{1}{2}\int_{v_\text{i}}^{v_\text{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{1+v}+\frac{1}{2}\int_{v_\text{i}}^{v_\text{f}} \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{1-v} \\ & = &\left[\frac{1}{2} \ln (1+v) - \frac{1}{2} \ln (1-v)\right]_{v_\text{i}}^{v_\text{f}} \\ & = & \frac{1}{2} \ln \frac{1+v_\text{f}}{1-v_\text{f}} - \frac{1}{2} \ln \frac{1+v_\text{i}}{1-v_\text{i}}\end{eqnarray}

Unlike the Newtonian case, the gain in speed our rocket can make does depend on the speed it starts at, so we can’t do the same thing of setting \(\Delta v = v_\text{f}-v_\text{i}\). Instead, we’ll just have to say we’re going to start in our rocket’s rest frame, so \(v_\text{i}=0\).

Under this condition, we get

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): $$\ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} = \frac{1}{2v_\text{e}} \ln \frac{1+v_\text{f}}{1-v_\text{f}}$$

That’s the relativistic rocket equation, but it’s not in a very usable form yet. We need to rearrange it so we can get \(v_\text{f}\) as a function of the other variables.

The first step, I suppose, is to exponentiate both sides to clean up the logarithms.

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): $$ \left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{2v_\text{e}} = \frac{1+v_\text{f}}{1-v_\text{f}}$$

Next up: multiplying out, grouping like terms.

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): $$\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{2v_\text{e}} (1-v_\text{f}) = 1+v_\text{f}$$

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): $$ \left(1+\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{2v_\text{e}} \right) v_\text{f} = \left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{2v_\text{e}}-1$$

Multiplying it all by \(\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{-v_\text{e}}\), then dividing out \( \left(\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{v_\text{e}} + \left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{-v_\text{e}} \right) \), we arrive at

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): $$v_\text{f} = \frac{\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{v_\text{e}} - \left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{-v_\text{e}}}{\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{v_\text{e}} + \left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{-v_\text{e}}}$$

We have what we were looking for, but it’s a troublesome-looking thing. However, it does look kinda similar to something more familiar: the hyperbolic tangent function, \( \tanh x = \frac{\exp(x) - \exp(-x)}{\exp(x)+\exp(-x)} \). Can we write this in terms of a \(\tanh\) function? Yes: because \(\exp (\ln x) = x\), we can replace all of those \(\left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{v_\text{e}}\) terms with \( \exp \left( \ln \left( \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)^{v_\text{e}} \right) = \exp \left( v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)\).

Supposing we do that, we get

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): \begin{eqnarray}v_\text{f} &=& \frac{\exp \left( v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right) - \exp \left(- v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)}{\exp \left( v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)+ \exp \left(- v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)} \\ & = & \tanh \left( v_\text{e} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right) \end{eqnarray}

We can’t assume we have natural units in general, so we need to reinsert all our factors of \(c\), i.e. all our velocities turn back into \(\frac{v}{c}\). Thus the final form of the relativistic rocket equation is

- relativistic case, \(v_\text{i}=0\): $$ v_\text{f} = c \tanh \left( \frac{v_\text{e}}{c} \ln \frac{M_\mathrm{i}}{M_\mathrm{f}} \right)$$

OK. Wow. Take a deep breath. That took some working out. If you’ve followed this far, especially if you’re working through the equations yourself, you should feel pretty proud. At least 17 smugs.

Before we leave off, let’s have a look at how the function behaves in action.

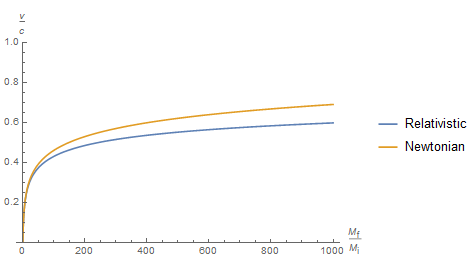

According to Atomic Rockets, a fusion rocket might have an exhaust velocity up to around (under very optimistic assumptions) \(v_\text{e}=0.09c\), which we’ll call \(v_\text{e}=0.1c\) because we don’t need to be too precise. To improve on that, you need to be doing some rather questionable things with black holes or antimatter.

Let’s say the payload of our spaceship - the stuff we don’t eject at \(0.1c\) in the fusion torch - weighs 1 unit. Let’s see how fast we can get with different amounts of reaction mass (the amount stuff we do launch out the back, in this case hydrogen isotopes transformed into helium by the fusion)…

I’ve put the maximum mass ratio really high here, far higher than any plausible rocket. At the high end of this graph, you have a metric tonne of reaction mass for every kilogram you want to take with you. It gets you to about \(0.5-0.6c\).

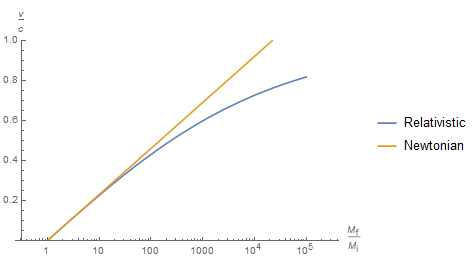

We see that the relativistic rocket equation grows more slowly than the Newtonian one. To make the relationship clearer, let’s switch the \(\frac{M_\mathrm{f}}{M_\mathrm{i}}\) axis to a logarithmic scale and push the mass ratio maximum even higher.

The Newtonian rocket equation predicts that you will exceed the speed of light somewhere between mass ratios of \(10^4\) and \(10^5\), which is impossible in special relativity. The relativistic curve slows down, approaching the speed of light but never reaching it short of an infinite mass ratio (i.e. you have no rocket left at the end).

Regarding the mass ratios: the Saturn V rocket used multiple stages to achieve an effective mass ratio of (by my calculation) 36. At that mass ratio, with this fusion rocket, we reach a respectable \(0.35c\), with about \(0.01c\) difference between the two equations. Unfortunately that’s not going to do much in terms of letting us use relativistic time dilation to shorten our experience of the trip, since the time dilation factor factor at this speed is only around 1.1.

What about more out-there rockets? For example… antimatter-annihilation rockets?

According to Wikipedia, when you take into account the fates of various annihiliation products, a hydrogen-antihydrogen annihilation rocket emitting pions directed out the back of the rocket using magnetic fields has an effective specific impulse of around \(0.6c\). Unfortunately we can’t get anything like the mass ratio we can with plain hydrogen, because antimatter is extraordinarily difficult to produce!

Not to mention terrifying to contain - I believe the idea is to use as-yet undeveloped 'magnetic bottles’ to maintain antimatter at temperatures of a few K, but should any matter come in to contact with it (e.g., an errant cosmic ray…), it will heat up and explode against its containment vessel, instantly releasing all the vast energy we were hoping to turn into speed for our interstellar voyage. It would be bad news.

Anyway, assuming we somehow could carry all that antimatter, we’d hit a fantastic \(0.97c\).

I think I’ll leave it there for now.

For the next post in this series, we’ll talk about acceleration in special relativity and use the above equation work out a model of an interstellar voyage in detail: the time it would take, the time experienced by the crew, energy requirements, that kind of thing. Hopefully, everything you need to describe a burn + coast + burn mission to another star!

Comments

mark k

what about using the blue shifted cosmic microwave background as a source of energy?