originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/863420...

It’s a common thing in sci-fi: somebody writes a huge message on the moon that people can read on Earth.

Well, maybe you want to do this too! I’m sure you have a very good reason. Here, then, is a scientific guide to writing on the moon.

Presumably we want people to be able to read our message, so we should write it large enough that most people can read it without a telescope, binoculars etc.

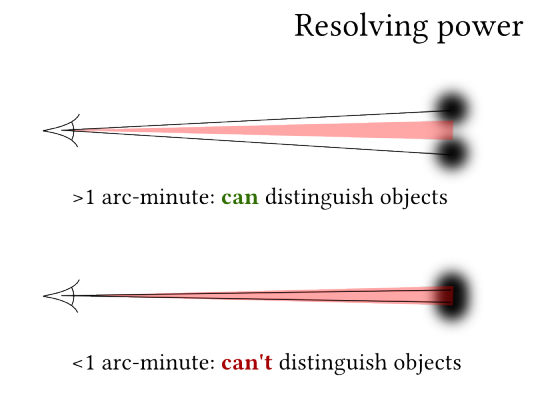

The human eye’s acuity varies a lot, but “normal” (20/20) vision is apparently considered as being able to resolve two things separated by a distance of one arc-minute (\(\frac{1}{60}^\circ\)). This corresponds to being able to distinguish between the ten Snellen optotypes when they’re five arc-minutes high. We need to write our letters at least that big if anyone is going to read them, and probably much bigger since we won’t only be using Snellen optotypes, and we won’t be writing the characters as maximum-contrast black on white.

The size of the moon in the sky varies between 29.3 and 34.1 arc-minutes depending on where it is in its orbit, so we need our letters to take up at least a sixth of the moon, and probably quite a bit more.

The moon is (close to) a sphere, but if we write the message close to the ‘middle’ of the moon seen from Earth (that is, the nearest point on the moon to Earth) then it won’t be too far off writing on a flat moon-sized disc and we won’t need to worry too much about distortion. (The moon is tidally locked, so our message won’t move around on the surface as seen from Earth).

Here is a free image of the moon (from Wikimedia Commons):

With the naked eye, there’s no way we can see all those pretty craters in that much detail. Since the human eye can only resolve one arc-minute, the pixel diameter should be about the same as the angular diameter in arc-minutes. Let’s scale it down so the moon takes up 34 pixels.

We won’t be able to write a very long message! Let’s go with 'hello’ as a sample message.

That 'hello’ is seven pixels (seven arc-minutes) tall. You can see it would still be a little hard to read.

To make that message appear, we need significantly change the albedo (basically, shininess) of all the areas of the moon underneath the black pixels. How much area is that? Well, the moon has an average diameter of \(3474\unit{km}\), so in the disk approximation, each pixel is roughly \(100\unit{km}\) on a side. Our 'hello’ takes up 49 pixels, so (rounding to one sig fig) we need to cover about 500,000 square kilometres - roughly the area of France.

I can think of three ways we probably couldn’t achieve that: launch explosives at the moon to create blast craters, shine an enormous laser at the moon to burn the areas to make them darker, or paint the moon with some dark or super-bright substance.

Nuclear missiles

I said explosives. On a moon scale, that means nukes.

As it happens, the US military has already done a lot of the work of thinking about how to launch a nuclear missile at the moon. This was during the early part of the space race, when the Soviets were clearly doing better at space than the USA.

The US air force thought it might be a good idea to show off their ability to fly rockets and blow things up if they nuked the moon. (They had various scientific aims in mind as well). This was Project A119. They wrote various papers and reports about this plan, but only one has not since been destroyed: A Study of Lunar Space Flights, Volume I. (Volume II got destroyed.)

A select line:

It is also certain that, unless the climate of world opinion were well-prepared in advance, a considerable negative reaction could be stimulated.

Well, guys. You don’t say!

Bizarrely, one of the members of the project was then-PhD student Carl Sagan. It’s thanks to one of his biographers that the project came to public attention.

The paper has lots of fascinating stuff about the state of lunar knowledge in 1959, and the various things that could be done to improve it with seismometers, telescopes and nuclear bombs. It has cute handwritten equation and ominous notes about the advantages to US propaganda if the Soviets contaminated the moon with bacteria. Unfortunately it seems to have relatively little information about the behaviour of the blast, or what the crater looks like after the nuke has gone off. Sections 2 and 9 are apparently in the destroyed Volume II, and I guess that kind of thing is to be found there.

So let’s see what we can guess ourselves. The effects of a nuclear weapon in the tenuous, near-vacuum atmosphere of the moon aren’t going to be much like the effects on Earth. There’s no air to convect up and create a mushroom cloud or carry shockwaves.

Still, evidence from Earth might still be relevant. Let’s consider an upper bound to the crater we might make. The USA, always willing to try out absolutely every terrible idea involving nuclear weapons, ran Operation Plowshare to study potential peaceful uses such as large earthworks (yes, that is an idea that someone actually had). As part of the operation, they detonated a 100-kiloton hydrogen bomb 200m underground, called the Sedan test.

The crater has a diameter of about 400m, and looks like this (source):

I spot a few things about this crater that would be relevant to leaving a mark on the moon. The crater’s pretty much the same colour as the surrounding dirt, but there is a large dark shadow. This is pretty similar to what lunar craters look like. Now, we can see lunar craters from Earth (though not usually with the naked eye) - but they’re usually much bigger, up to about 300km. The Sedan crater would be lost in the mess.

For an illustration of the scale we’re dealing with, Tycho is one of the most prominent craters. It has a diameter of about \(88\unit{km}\). I coloured it in bright red on the big moon picture, and scaled the picture down to \(34\times34\) again.

The 88km Tycho takes up less than one pixel (it’s a darker red).

If we’re going to draw on the moon with nukes, we’re going to need a ridiculous number of nukes - far more than the ridiculous number of nukes we already (shouldn’t) have. Let’s work out how many.

On the moon, I’d imagine the crater would be bigger, due to reduced gravity and there being less atmosphere to sap energy from the dirt flying about. On the other hand, it would be difficult to dig into the moon to detonate our bombs underground.

As it turns out, we’re not the first person to think about this! Someone at the University of Washington has created a web-based calculator to estimate crater sizes from various kinds of explosions, using a database of craters. Handily, it includes parameters for the moon. Setting off a half-megaton nuke at ground level on the moon predicts a crater rim diameter of 430m. Upping that to the 50 megatons of the largest nuke ever detonated (the Tsar Bomba) brings the crater rim diameter up to about 1.5km. Mind you, we’re probably running wayyy ahead of their data here.

I plugged in a series of numbers into the model, and it seems to be calculating sizes based on a power law in the yield with exponent 0.27. The area is proportional to the square of the diameter, so that will have exponent 0.54.

What kind of nuke should we use?

It sounds like the crater size grows much slower than the yield of the explosion, so if we want to mark out a large area, we’d be better off spending our rocket payload mass on lots of little nukes instead of a few giant ones. That’s pretty much how later ICBMs worked anyway, with MIRV (Multiple Independently-targetable Reentry Vehicles) designs.

Raising masses from the Earth is very energetically expensive - we’ll be getting to that bit - so we want to maximise our area marked per unit mass. To know this, we need a relationship between the mass of the warhead and the yield of the device. This depends hugely on the design of the weapon, of course. Atomic Rockets states there is a theoretical maximum of around 1kg/megaton, and that a real US W88 warhead has about 500kg/megaton. If it is linear like those numbers hint, we should make our warheads as small as possible.

Let’s look at some actual small nuclear warheads. The smallest warhead the USA cooked up was the W54, which came in several variants, most infamously the Davy Crockett recoilless rifle. The most powerful variant seems to be the 'SADM’ (a bomb you carry in a backpack and leave somewhere), which could go up to a kiloton while weighing about 30kg, meaning it has at best 30,000kg/megaton - a worse ratio than the big warhead by a factor of sixty!

Looking at data for various warheads pulled from this rather nauseating list… I can fit a variety of things like a power law or just “it’s linear-ish above about 100 kilotons”, none are obviously “That’s it!”. That’s not really surprising.

Instead, I’ll just consider existing warheads. Suppose we have room for mass \(M\) on our rocket, and we want to maximise the area of moon we can cover. We have warheads of mass \(m\), each covering area \(a\) of moon with dark crateriness. Then the area of moon we cover is simply \(\frac{aM}{m}\). For the sake of picking the best warhead, we can ignore \(M\) (set it to 1). Applying this measure to a selection of warheads, the best one I checked seems to be the W80, which weighs \(132\unit{kg}\) and blasts a crater \(330\unit{m}\) wide with an area of \(\about86000\unit{m^2}\), that is, \(0.086\unit{km^2}\).

Here’s what it looks like (from Wikimedia Commons):

How many do we need?

Based on the 'hello’ we drew earlier, we’re probably looking at roughly 100,000 square kilometres of dark cratery stuff per letter (roughly the area of South Korea). Performing the division, we find we need about a million W80 warheads per letter.

In 1985 at the peak of the Cold War, Wikipedia informs me there were 68,000 active weapons around. Today there are about 17,000 left. Most of these would not be as efficient at producing smashed up lunar surface as the W80.

Is it actually possible to make a million W80 warheads using the nuclear materials on Earth? The author of the Nuclear Weapons Archive speculates that the design contains uranium, plutonium, and beryllium. Plutonium is produced from uranium in a nuclear reactor, and the process is slightly different for reactor-grade and weapons-grade plutonium. I’m having trouble finding out how much plutonium you actually need to make a bomb, though. The above-linked page seems to suggest it’s around 6kg, but that might only make a small bomb.

Worldwide, there are apparently 6,306,300 tonnes of recoverable uranium. Most of that is U-238, which you can slowly turn into plutonium. You would have to mine that uranium, enrich it, turn some of it into plutonium, and very carefully build bombs out of what you’ve got.

How do we get them there?

Suppose you got your hands, by magic, on an appropriate pile of W80 warheads. How will you get them to the moon?

To change your speed/direction in space, there are only two things you can do: fling a piece of you (such as some water or electrons you have on board) opposite the direction you want to accelerate, or have something else crash into you (such as solar wind, a nuclear explosion, or a big laser on your home planet). All propulsion technologies amount to doing one of those things.

For the first kind, your flight is governed by the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation. This says the amount you change your velocity (your 'delta-v’) following a burn of your rocket depends on two quantities: the ratio of mass you had before the burn to mass you’re left with afterwards (the 'mass ratio’) and the speed at which you chuck the mass out the back (your rocket’s 'exhaust velocity’ or 'specific impulse’).

To get to the moon, a quick lookup on this handy table tells us we need about 15km/s of delta-v to reach the moon from Earth.

We can rearrange the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation to tell us how much mass a given rocket can carry to the moon: \begin{align}\Delta v &= v_e \ln \frac{m_\mathrm{empty}+m_\mathrm{payload}+m_\mathrm{fuel}}{m_\mathrm{empty}+m_\mathrm{payload}}\\ m_\mathrm{payload}&=\frac{m_\mathrm{fuel}}{\exp \left(\frac{\Delta v}{v_e}\right) - 1} - m_\mathrm{empty}\end{align}

For a multi-stage rocket, this is harder: in general you’ll get a polynomial in the payload mass of order the number of stages.

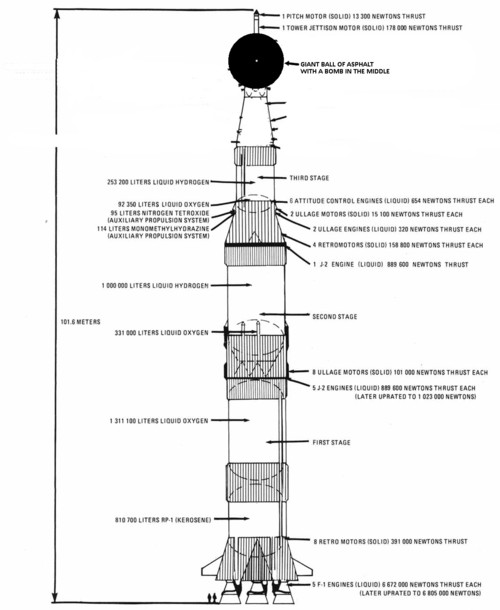

Fortunately, for the Apollo missions’ Saturn V, someone has already done this calculation. The Saturn V can carry 45000kg to a trans-lunar injection. If we brush over the need for a targeting system to put these nukes in the right places, each Saturn V could carry 340 W80 warheads.

So if we carried our nukes with the Saturn V, we’d need about 3000 Saturn Vs per letter we write on the moon.

The Saturn V is one of the most powerful rockets ever made, and with most other kinds of chemical rockets, you’d need vastly more of them to carry your nukes if you can reach the moon at all.. But people are very inventive, and we’ve come up with all kinds of other propulsion systems. We could take advantage of our apparent ability to conjure nukes out of thin air to build Project Orion - after all, what better way to carry nukes to the moon than by throwing nukes out the back of our spaceship?

One final little note: you are, inevitably, going to have lots of launch failures with your thousands of launches. Now, exploding rockets are bad enough, but each of your rockets has a stack of several hundred nuclear bombs on the top. As far as I understand it, you shouldn’t have any nuclear explosions (triggering a nuclear explosion requires the internal explosive lenses to go off with very precise timing), but you will squirt highly radioactive materials everywhere downwind of your launch site.

Giant laser

I don’t think we’ve managed to be supervillain enough with our plan to launch tens of thousands of rockets filled with millions of nuclear bombs. Could we save the effort of launching anything into space by shining giant lasers on the moon?

Shining lasers on the moon is something that has already been discussed in What If? We don’t want to illuminate or de-orbit the moon, though - merely darken the surface over an area the size of France.

Let’s go back to Atomic Rockets, which (of course) has an extensive section on shining lasers on things in space. Laser focussing is limited by diffraction. To focus laser light on a small area, you need to make your aperture (your mirror, lens, etc.) as large as you can. We’re in the Fraunhofer diffraction regime, and the pattern produced - the Fourier transform of a hard-edged circle - is called the Airy disc.

The important result is that the minimum radius of the beam at a distance \(l\) from an aperture of diameter \(d\) with light of wavelength \(\lambda\) is \(1.22 l \lambda d\).

Now, we want to focus our laser on the moon, the nearest point of which \(355,000\unit{km}\) away from us when the moon is as near as it gets.

We’re trying to melt the rock of the moon. According to this page about laser damage to materials, our laser will melt a layer of the surface at around \(10^6 \unit{W\cdot cm^{-2}}\), and vaporise some of it in the range \(10^6-10^8 \unit{W\cdot cm^{-2}}\). I think those might apply just to iron though? The rest of the page goes into detail about how to estimate the effects given the properties of the material.

I found details of lunar regolith’s physical properties (or rather, a simulant) from this NASA contractor report into getting thermal energy from the regolith. The important numbers are, at temperature \(T\):

- melting temperature: \(1440\unit{K}\) (though different parts melt at different temperatures over a range of about \(50\unit{K}\))

- average latent heat of fusion: $$H_f = 161.2 \unit{kJ\cdot kg^{-1}}$$

- density (granular, as at the surface): $$\rho = 1800 \unit{kg\cdot m^{-3}}$$

- specific heat: $$C_p = \left(-1.8485 + 1.04741\log\left(T/\unit{K}\right)\right) \unit{kJ\cdot kg^{-1} \cdot K^{-1}}$$

- thermal conductivity: $$\kappa = \left(0.01281 + 4.431 \times 10^{-10}\left(T/\unit{K}\right)^3\right) \unit{W\cdot m^{-1} \cdot K^{-1}}$$

We don’t really need to dig a deep hole. We’d just like to melt the top layer of dust so that it crystallises, hopefully changing its appearance. Rock is very difficult to vaporise, so I’m going to neglect that.

We pump in energy from our laser, heating up the rock. The rock cools down through heat being conducted into the rest of the moon, and hot rock radiating heat away. What we’ll do is estimate the power lost from each of those, so we can find the biggest and declare the rest of them negligible, like true physicists.

The radiation intensity (power per unit area) is the usual \(e\sigma T^4\) with emissivity \(e\) and \(\sigma\) the Stefan-Boltzmann constant. For conduction, we can use the approximation of a point source at the edge of an infinite slab described in the above link. Ideally, we’d solve a combination of conduction and radiation: have a temperature-dependent boundary condition at the edge of our slab, and solve the heat equation. That’s very difficult; I’m not sure how you’d treat it.

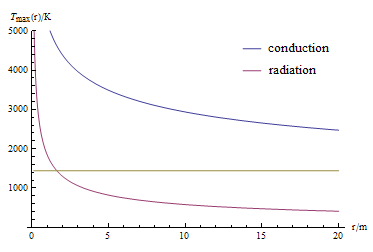

So let’s imagine instead that we have a roughly constant temperature (the melting temperature) inside our laser spot, and outside it falls off as the point-source solution. If our spot has radius \(r\), it’s losing \(P_\text{conduction}= 2 \pi \kappa r (T - T_0)\) to conduction into the surrounding material and \(P_\text{radiation}=\pi r^2 e \sigma T^4\) as radiation into space.

If we plot these against each other, we see that at pretty much every plausible radius, radiation dominates by orders of magnitude. You can’t even see the conduction power on the plot. If you do the calculation, conduction only becomes more significant for an 8mm target.

We do have to actually heat the rock up enough to reach that melting temperature, though. Let’s quickly find the maximum temperatures we can reach under these two regimes.

Suppose power \(P\) is being shone by our laser (and keeping the emissivity = absorptivity assumption). For radiation, that’s $$T_\text{max,rad} = \left(\frac{I}{σ}\right)^{\frac{1}{4}} = \left(\frac{P}{\pi r^2\sigma}\right)^\frac{1}{4}$$For conduction, we need the full expression for conductivity, which we’ll write for simplicity as \(a + bT^3\); then \(P_\text{conduction}\) looks like $$P_\text{conduction}=2\pi r(a + bT^3)(T - T_0)$$which we can get Mathematica to solve. We can plot these.

At a range of laser powers (here we have 2MW), the limit is always radiation, and we only exceed the melting temperature of the lunar regolith for a very tightly focussed laser indeed! The radius we have to hit grows as the square root of the power we’re focussing, getting as high as three and a half metres for a 10 MW laser!

What kind of laser should we use? X-ray lasers are good, because the small wavelength means we can focus the light more tightly. A free-electron laser is the most efficient kind Atomic Rockets mentions (which is important, because there is going to be an awful lot of waste heat coming out of our laser). The US military wrote a paper about their plan to make a multi-megawatt free-electron laser that fits on a ship. (We could also use bomb-pumped lasers to get X-rays, but if we’re only burning a three-metre circle at a time, we’ll need an even more ludicrous amount of bombs than the last plan.)

To focus our beam into a three-metre radius target with an X-ray laser (wavelength about \(10\unit{nm}\)) means we have to have our aperture be about \(1.2\unit{m}\) wide - easily doable! Mind you, with the amount of energy we’re about to pump through it, that mirror will probably melt and we’d need a much bigger one to keep it cool.

We need to shine our laser on each spot long enough to melt it. This means first raising the temperature up to \(1440\unit{K}\), then providing the latent heat of fusion. Let’s say we hope melt a centimetre into the rock. Then we need to melt about \(0.3\unit{m^3}\), which is \(500\unit{kg}\) with the density above.

First we need to warm it up. The specific heat capacity varies with temperature, so we need to integrate it; from \(100\unit{K}\) to \(1440\unit{K}\) this gives us \(6600\unit{kJ\cdot kg^{-1}}\), so we need to put about \(3\unit{GJ}\) into this area to raise it to melting temperature (goes down to about \(2.5\unit{GJ}\) if we heat up a warm moon). We can drop that by a factor of 10 if we only melt a millimetre.

The latent heat of fusion is much smaller than that, we can pretty much ignore it.

Well, with a \(10\unit{MW}\) laser, if we weren’t losing heat to radiation we’d have to keep it pointing at the same patch of rock for \(300\unit{s}\) (five minutes); we can drop that to half a minute if we only melt a millimetre. But we are losing heat to radiation, so as it gets hotter, we get slower to heat it up further. We have to solve a differential equation: $$\df{E}{t}= \df{E}{T} \df{T}{t} = m C_\text{p} \df{T}{t} =10\unit{MW}-P_\text{radiation} -P_\text{conduction} $$I did this numerically, in Mathematica. As expected, our rock heats up quickly to begin with, and slows down to stop at an eventual maximum temperature. It passes \(1440\unit{K}\) at about \(500\unit{s}\). (After that point, the solution is no longer valid as a melt is present).

So, finally, we have an answer - using a kinda-implausible 10MW X-ray laser, we can melt a three-metre radius circle of moon every eight minutes. It’s going to take us a very long time to melt out our message - about 54000 years if we have only one laser. We need more lasers. We’ll get it done in a year if we have about 50,000 10MW free-electron lasers.

Our lasers are going to draw a huge amount of power: \(500\unit{GW}\) minimum, and assuming theoretical maximum 65% efficiency, more like \(800\unit{GW}\). This is actually not that bad for a project on this sort of scale: Wolfram Alpha offers that it’s about a quarter of the power used by the USA.

Sounds good, right? We’ve neglected the atmosphere. Our lasers will be attenuated by the atmosphere, which will heat it up, which will spread the beam out in a process called thermal blooming. Ideally, we’d want to put our laser fleet in space to bypass this, but then radiating away the waste heat from our lasers becomes a much more difficult problem. Maybe we can compromise a bit and put them up a mountain next to some observatories.

The other overwhelming problem’s going to be aiming the lasers. Even a super-tiny wobble is going to be magnified enormously by the fact that we’re aiming at something at least \(355,000\unit{km}\) away. If we err in our aim by even 1/100,000 radians (1/200 degrees), we’re already kilometres away from our target. This will severely compromise our ability to deliver power to a tiny area, as we need to, probably destroying our ability to melt the rock at all. Our laser dots will skate over the moon, slightly warming up the regolith and doing little else.

Painting the moon

Those ideas seem to demand some rather formidable piles of weapons, and people might find that disagreeable no matter how much you swear it’s for purely artistic purposes. Another, less immediately supervillainous possibility is to scatter either something very bright and shiny or something very dark over the appropriate areas of moon.

According to NASA, the moon has a Bond albedo of about 0.11 (it reflects 11% of incident sunlight) and a visual geometric albedo of about 0.12 (it reflects about 12% of what an idealised diffusing disc would). But we are most interested in the normal albedo of bits of the surface. According to this wiki about the moon (the moon has its own wiki! gosh), the estimated normal albedo of bits of the moon varies between 0.06 and 0.18.

What could we use to recolour the moon?

We need something that’s very dark or light and also very abundant on Earth (since we need to cover a France worth of ground with it). It needs to stay in place over the rather dramatic temperature swings between 100K and 390K at the equator, so something the melts and evaporates in that range (such as water ice) is no good. Bright colours might help us make our message readable, since the moon is very grey.

Possibility one: petrochemicals. Fresh asphalt (apparently “tarmac”, which is what we normally call it here in the UK, is actually an old thing that’s no longer made) has a very low albedo of about 0.04. That’s slightly darker than the darkest bits of moon, and much darker than the brighter bits.

How much asphalt do we need to put down to get our message? And how can we distribute it, considering that it’s very very sticky? Probably we should smash it up into small pebbles. Then, when our rocket gets near the moon, we can blow it up; instead of a rocket, an expanding spherical cloud travels the rest of the distance, automatically dispersing the asphalt across the moon. (Basically, this is a shrapnel shell).

How much?

We don’t need or want to cover the surface too thickly, but it needs to be seen.

This paper (on Google Books) talks about the effect of dusting a surface (in this case, ice) on albedo. As you’d probably imagine, the more thickly the surface was coasted with the dust, the closer its albedo approached that of the dust. Their dirt has a bulk density of \(450 \unit{kg \cdot m^{-3}}\), whereas solid asphalt has a density of \(1300 \unit{kg \cdot m^{-3}}\). They got the initial albedo of their ice close to that of the dirt at about \(0.45 \unit{kg \cdot m^{-2}}\), corresponding to \(0.001 \unit{m^3}\) of dirt per square metre (consistent with the 1mm thickness that they recorded). Coating the moon with asphalt dust to the same thickness would require about \(1.3g\) of asphalt per square metre, which doesn’t sound too bad.

The experiment described in the book takes place on a smoothed out, flat ice sheet, which is very unlike the surface of the moon. The moon’s surface is very rough and pitted; some of our asphalt would fall in holes and wouldn’t darken it as much, but on the other hand all the craters and so on reduce the albedo. (It’s complicated because lunar regolith has retroreflective properties rather than being purely diffusive).

Anyway, assuming \(1\unit{g \cdot m^{-2}}\) is enough-ish, what mass of asphalt are we lifting into space? Using our \(100,000\unit{km^2}\) estimate of letter size again, we need to lift about \(10^8\unit{kg}\) of asphalt to the moon. If we use the Saturn V as our launch vehicle again, we’ll need about 2,000 Saturn Vs per letter. We’re actually doing better than we were with the nukes, which I wasn’t expecting!

Each one carries \(45,000\unit{kg}\) of asphalt, making up a volume of \(45 \unit{m^3}\), or a 5m radius sphere. That’s not implausibly big, but it still wouldn’t fit inside the first stage of a Saturn V. Probably it would be a bit bigger if we smash it up to fine powder before the launch, which we should be doing, since that would be easier than doing it in space.

Here’s how that sphere would compare with the Saturn V (from Wikimedia Commons):

That sphere of asphalt dust will disperse to cover 45 square kilometres to a depth of about a millimetre.

To disperse our asphalt across the surface, we need to spread it out a lot more than that. I imagine we can do this with a conventional bomb. Unlike a terrestrial explosion, there’s no atmosphere to slow down the debris cloud’s expansion, so once it explodes, it will keep spreading out until it reaches the moon. If the cloud is flying straight for the centre of the moon, it will spread out in a circle. It’s likely to have some angular momentum with respect to the moon, though, in which case it will have a high tangential speed by the time it reaches the surface, elongating the circle into an ellipse.

If we explode our sphere a distance \(d\) from the moon, and our asphalt disperses with an average velocity \(u\), while our rocket is travelling at constant speed \(v\) relative to the moon, the radius of the patch we darken will be \(r=\frac{ud}{v}\). The centre of the patch will be much darker than the edges; to alleviate this a bit, we could perhaps pack the asphalt dust into a disc-shaped plate with the bomb at the centre.

The dynamics of shrapnel seem to be (as with everything) quite complicated. For something simpler, we might imagine that collisions within the dust make it behave like a cloud of gas, with velocities distributed according to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Supposing our bomb imparts an energy \(U\) to moving our 'gas’ of \(n\) particles (less than the total energy released by the bomb, because the bomb heats up the individual lumps of asphalt too), this is associated with a temperature $$kT=\frac{2}{3}Un$$The mean speed of the particles in a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is $$2\sqrt{\frac{2kT}{m\pi}}$$ where \(m\) is the mass of a single particle. It doesn’t really matter how big our particles are in fact, since \(mn\) is the total mass of the asphalt, \(M = 45,000\unit{kg}\). So the average speed is just $$2\sqrt{\frac{4U}{3M\pi}}$$

OK, now we’re in a position to work out how big to build the bomb. We probably want to do it fairly close to the moon, since that will allow us to aim at the right place, and reduce the complication arising from our fragments being in different orbits and the speed of the centre of mass of the cloud varying.

If our trans-lunar flight is a Hohmann transfer orbit from the Apollo parking orbit to the moon, we’ll approach the moon at about \(200 \unit{m\,s^{-1}}\). Picking a number rather arbitrarily, suppose we explode the rocket at \(10,000\unit{km}\) from the moon, about 1/40 of the distance between moon and Earth. Then, our particles must disperse at \(u=\frac{vr}{d}=75\unit{mm\,s^{-1}}\), and the total kinetic energy our bomb must impart is \(150\unit{J}\). This is a tiny amount of energy (to the point that I think I’ve probably made a mistake): we could achieve it with less than a gram of TNT. Perhaps you shouldn’t even use a bomb at all, but some more efficient mechanical means to push the dirt outwards in a flat-ish disc.

\(10,000\unit{km}\) is possibly a bit far from the moon, but I expect the general principle will still hold: by detonating far from the moon, you can disperse the dust a long way with very little energy.

One thing of note here: we’ve assumed that the smashed up asphalt dust will remain the dark colour of fresh asphalt. As it gets older, asphalt becomes significantly lighter, so our message will likely not remain visible for long.

In conclusion

So overall, it seems (even granting that this has been treated with some very generous assumptions) lifting giant lumps of asphalt into space on thousands of rockets might be the best way to write a message on the moon. I’m kind of surprised by that! Before I started, I was sure the dirt would be much too heavy, so nukes would be the best way.

More seriously, this was a silly idea I’ve been planning to write up for ages. I’m kind of happy about all the really interesting things it’s ended up touching on. I hope you were entertained too (tell me! and please consider sharing it!). If you see any errors (there are definitely errors), large or small, please contact me so I can correct them! And if you have any other ideas for better ways to write on the moon (an army of robots, perhaps), let me know. This is important information for aspiring villains everywhere.

Comments