originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/101232...

You’re hoping to fly a rocket to another star system, light years away.

In the last post, we worked out the maths of what it takes to change your velocity by significant fractions of the speed of light, and found the relativistic rocket equation: $$ v_\text{f} = c \tanh \left( \frac{v_\text{e}}{c} \ln \frac{M_\text{i}}{M_\text{f}} \right)$$

In this post, we’ll start to look through a mission to a distant star system. We’ll take a pretty detailed look at accelerated motion in special relativity, we’ll see how constant acceleration produces event horizons like black holes, and we’ll start taking a look at how we can exploit time dilation to make long space missions shorter for the crew.

(As serious as all that sounds, I’m hoping you can follow all the maths with just the amount calculus you learn at A-level. If you’d rather dodge most of the maths, skip down to ‘constant acceleration’ for the bit about spaceships.)

This post originally began with an explanation of relativity concepts, but that ended up growing big enough to become its own post. There you can get introduced to things like spacetime diagrams, world lines, and what a four-vector is.

Like in the first post, I’m going to use a system of 'natural units’ in which the speed that does not change in Lorentz transformations, \(c\), (which is the speed that light travels at) is \(1\). This means space and time have the same dimension. Seems weird, but it makes everything much easier not to be following around every little factor of \(c\).

Motion!

In Newtonian physics, we consider each particle’s position as a function of absolute time, and calculate their velocities and accelerations by differentating the position with respect to that absolute time. So we get equations like $$m\frac{\dif^2 \mathbf{r}}{\dif t^2}=\sum F$$and the motion of a rocket with constant acceleration \(a\) is quadratic in the absolute time, e.g. $$x= \frac{1}{2} a t^2 + v_0 t + x_0$$for a rocket accelerating in the \(x\) direction.

In relativistic physics, things are a bit trickier, because the acceleration changes between different reference frames. But the same basic ideas still apply - we just have to use proper time instead of the absolute time.

So, we have a particle following a world line given by specifying its space and time coordinate four-vector as a function of its proper time, which we write as \(x^\mu (\tau)\). (This tells us where and when the particle is in some reference frame, for each point in the time it experiences. So we can say e.g. “where is it at \(\tau=2\text{s}\)?” and we get a list of space and time coordinates).

We can differentiate these functions with respect to proper time \(\tau\), finding the particle’s four-velocity $$V^\mu=\frac{\dif x^\mu}{\dif\tau}$$

The four-velocity is the relativistic analogue of velocity. We can relate it to the three-velocity (that is, the traditional Newtonian velocity calculated using that frame’s time coordinate) in a particular frame, \(v_i=\frac{\dif x^i}{\dif t}\) where \(i\) is 1,2, or 3, and \(t=x^0\), using the relationship \(\dif t=\gamma_v \dif\tau\).

(Here $$\gamma_v=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-v^2}}$$where$$v^2=\sum_{i=1}^3 {v_i}^2$$\(\gamma_v\) is a very important quantity which we use all the time in special relativity.)

We can explain that relationship using the notion of an 'instantaneously co-moving frame’ (aka 'instantaneous rest frame’). This means we imagine an inertial frame of reference \(S’\) in which the particle happens to be stationary, just for that specific instant.

That means that, for that instant only, the change in the coordinate time in \(S’\), written \(\dif t’\), is the same as the change in the particle’s proper time \(\dif\tau\).

Now we can transform between the inertial reference frames using the Lorentz transformation. If the spaceship is moving at speed \(v\) in another inertial frame \(S\), we need to do a transformation with speed \(-v\) to get back to that frame.

So if a differential time \(\dif t’=\dif\tau\) passes in the co-moving frame, during which the spaceship travels no distance as the frame is co-moving so \(\dif x’=\dif y’=\dif z’=0\), the Lorentz transformation tells us that a time \(\dif t=\gamma_v \dif t’ = \gamma_v \dif \tau\) passes in the \(S\) frame.

We can repeat this procedure for every point on the spaceship’s worldline, so that gives us the relationship $$\dif t=\gamma_v \dif\tau$$

OK, so, let’s have a look at the components of the four-velocity…

- The first one is \(\frac{\dif x^0}{\dif\tau}=\frac{\dif x^0}{\dif\tau}\) which is \(\gamma_v\) as we just discussed!

- The other three can be found by the chain rule: $$\frac{\dif x^i}{\dif\tau}=\frac{\dif x^i}{\dif t}\frac{\dif t}{\dif\tau}=v_i \gamma_v$$where the \(v^i\) are the components of the three-velocity in this frame.

So we’ve found the components of the four-velocity to be \(V=\gamma_v(1, \mathbf{v})\), using a notation where we write the last three 'space’ components of a four-vector as a three-vector.

Let’s differentiate the four-velocity with respect to proper time again! So now we’ll get the four-acceleration, $$A^\mu=\frac{\dif V^\mu}{\dif\tau}=\frac{\dif^2 x^\mu}{\dif\tau^2}$$

The four-acceleration’s a relativistic analogue to acceleration, and like the four-velocity, we can relate it to the three-acceleration and three-velocity in a particular frame.

Unfortunately, this gets rather a lot more messy. I’ll go over the derivation in the next section, but if you want to just take that formula as read, you’re welcome to skip it

The components of the four-acceleration

OK, so we’ve got the rule linking proper time and coordinate time, which can be expressed as… $$\frac{\dif }{\dif\tau} = \frac{\dif t}{\dif\tau} \frac{\dif }{\dif t} = \gamma_v \frac{\dif}{\dif t}$$

We’re going to end up differentiating a few \(\gamma_v\)s with respect to \(t\).

First let’s differentiate $$v^2 = \sum_{i=1}^3 {v_i}^3$$We get \begin{align*}\frac{\dif}{\dif t}(v^2) &=\sum_{i=1}^3 2 v_i \frac{\dif v_i}{\dif t} \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^3 2 v_i \frac{\dif v_i}{\dif t} \\ &= 2 \sum_{i=1}^3 v_i a_i \\ &= 2\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{a}\end{align*}(where we’ve introduced \(a_i=\frac{\dif v_i}{\dif t}\). Using that, we have \begin{align*}\frac{\dif\gamma_v}{\dif t}&=\frac{1}{2}(1-v^2)^{-\frac{3}{2}}\frac{\dif }{\dif t}v^2\\&=\frac{\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{a}}{(1-v^2)^{\frac{3}{2}}}\\&={\gamma_v}^3 \mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{a}\end{align*}

With that in place, then, let’s get some components out of the box.

First of all, the 0th component is nice and straightforward using the relationships we just established\begin{align*}A^0 &= \frac{\dif V^0}{\dif\tau} \\&=\frac{\dif\gamma_v}{\dif\tau}\\&= \gamma_v \frac{\dif\gamma_v}{\dif t} \\&= {\gamma_v}^4 \mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{a}\end{align*}

The other three components \(A^i=\frac{\dif A}{\dif\tau} (\gamma_v v_i)\) are slightly more complicated; we have to use the product rule. So we get \begin{align*}\frac{\dif}{\dif\tau} \gamma_v v^i&= \gamma_v \left(\frac{\dif v_i}{\dif t}\gamma_v + v_i \frac{\dif \gamma_v}{\dif t}\right)\\&= {\gamma_v}^2 a_i + v_i {\gamma_v}^4 \mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{a}\end{align*}

We can write this out more nicely this way: $$A=\left({\gamma_v}^4\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{v},{\gamma_v}^2\mathbf{a}+{\gamma_v}^4\left(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{v}\right)\mathbf{v}\right)$$

Sweet.

The most important thing about this formula is that in an instantaneously co-moving frame, the four-acceleration is just \((0,\mathbf{a})\) where \(\mathbf{a}\) is the three-acceleration. Since the four-acceleration is a four-vector,so its magnitude is the same in every reference frame, the magnitude of the four-acceleration is always the acceleration that the particle 'feels’ (in the same way that you 'feel’ acceleration when you’re in e.g. a car or a rollercoaster).

OK, to summarise, the motion of a particle is given by specifying its worldline \(x^\mu (\tau)\), and by differentiating that with respect to \(\tau\) you get four-vector analogues to the velocity and acceleration. You can relate these to the coordinate accelerations and velocities.

Accelerating spaceships!

Let’s have a go at the motion of spaceships on relativistic missions.

We can reasonably assume that the rocket’s going in a straight line. (Let’s ignore any gravitating bodies, and assume the rocket is in empty space.) Let’s swivel our coordinate system so it’s going in the \(x^1\) direction. So we can ignore the \(x^2\) and \(x^3\) directions, and simplify the formulae above to just deal with a single space coordinate \(x\), single-component “three-velocity” \(v\), and single-component “three-acceleration” \(a\). And we’ll continue to use \(t\) for \(x^0\).

The dot products in the four-acceleration just become products of scalars, so we have \(A=({\gamma_v}^4 av, {\gamma_v}^2 a + {\gamma_v}^4 a{v}^2,0,0)\).

In an instantaneous rest frame \(S’\), as noted above the four-acceleration reduces to \(A’=(0,\alpha(\tau),0,0)\). We can apply the Lorentz transformation (with speed \(v\) in the \(-x\) direction) to find that in the inertial frame \(S\) we’re interested in, \(A^0=v \gamma_v \alpha(\tau) \).

Now we can equate the two formulae we’ve got for \(A^0\), and we get $$v(\tau)\thinspace\gamma_v(\tau)\thinspace \alpha(\tau) = {\gamma_v}^4 (\tau) a(\tau)\thinspace v(\tau)$$so we actually have a very simple relationship, $$\alpha(\tau)={\gamma_v}^3 (\tau) a(\tau)$$

Reversing this, we get $$\frac{\dif v}{\dif t}=(1-v^2)^\frac{3}{2}\alpha(\tau)$$This can give us an expression for the coordinate velocity as a function of proper time, using $$\frac{\dif v}{\dif t}=\frac{\dif\tau}{\dif t}\frac{\dif v}{\dif\tau}={\gamma_v}^{-1}\frac{\dif v}{\dif\tau}$$so$$\frac{\dif v}{\dif\tau}=(1-v^2)\alpha(\tau)$$.

We can seperate variables to solve this as $$\int_{v_0}^v \frac{\dif v’}{1-{v’}^2}=\int_{\tau_0}^\tau \alpha(\tau’) \dif \tau’$$assuming the ship has coordinate velocity \(v_0\) at a time \(\tau_0\). The integral on the left hand side is a standard integral which you can look up as being \(\arctanh (v)-\arctanh(v_0)\).

If we can assume the spaceship starts at rest (\(v_0=0\) at time \(\tau=0\), this leads to simple formula $$v(\tau)=\tanh\left(\int_0^\tau \alpha(\tau’) \dif \tau’\right)$$

For convenience’s sake, let’s define $$\psi(\tau) = \int_0^\tau \alpha(\tau’) \dif \tau’$$

OK, this is very useful indeed. Because now we know \(v(\tau)\), and using the identity \(1-\tanh^2 x = \sech^2 x\), we can find $$\gamma_v (\tau) = \left(1-\tanh^2 \psi(\tau)\right)^{-\frac{1}{2}} = \cosh \psi (\tau)$$

So, using the relationships we found much earlier for the four-velocity, we have $$V^0=\frac{\dif x^0}{\dif\tau} = \gamma_v = \cosh \psi (\tau)$$and $$V^1=\frac{\dif x^1}{\dif\tau} = \gamma_v v= \sinh \psi (\tau)$$

These equations can be solved by integration. Assuming we (or at least, our computers) can find the relevant integrals, that’s a complete parametric solution for the motion of a spaceship! (At least, one that’s at rest at some point in the frame we’re interested in, that’s only travelling in one direction, and assuming we know the proper acceleration for all time after that…)

Constant acceleration

OK, so suppose \(\alpha\) is just a constant, and does not change with \(\tau\).

It’s the mathematically simplest case, but there are good reasons you might want to fly a rocket that way. For example, if you can keep accelerating for a long time, you can use the acceleration of your spaceship to provide an equivalent of gravity for any crew you’re carrying. In that case, keeping the 'gravity’ constant is probably a good idea. (That kind of mission requires huge mass ratios though - more likely you’ll spend some part of the mission with your engines turned off! We’ll cover that next.)

In this case, the integral \(\psi (\tau)\) is particularly simple: it’s just \(\alpha\tau\), assuming as above that the clock starts at \(\tau=0\). So we’ve got $$\frac{\dif t}{\dif\tau}=\cosh\alpha\tau$$ and $$\frac{\dif x}{\dif\tau}=\sinh\alpha\tau$$Integrating, we get \begin{align*}t(\tau)-t(0)&=\alpha^{-1} \sinh \alpha\tau\\x(\tau)-x(0)&=\alpha^{-1} (\cosh\alpha\tau - 1)\end{align*}

Aha, now we can just use the identity \(\cosh^2 x - \sinh^2 x = 1\) to relate \(x\) and \(t\). This yields $$(x-x(0)+\alpha^{-1})^2-(t-t(0))^2=\alpha^{-2}$$

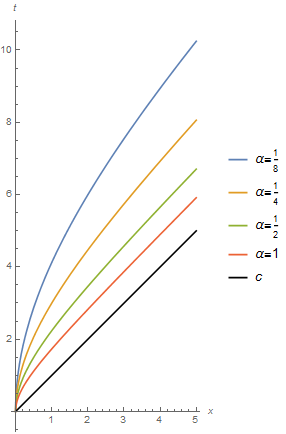

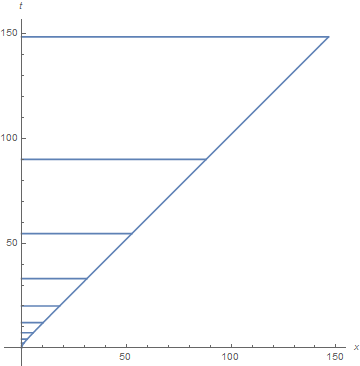

Oooh, that’s the equation of a hyperbola! Let’s take \(x(0)=t(0)=0\) and plot it for various values of alpha.

(don’t worry too much about the units here! they’re kinda arbitrary)

All of the worldlines start off vertical and bend towards the speed of light line at \(45^\circ\) as you go up the time axis. They get closer and closer to being parallel to that line forever, but always remain slightly steeper. Much as you’d expect, smaller accelerations take longer to approach the speed of light, and overall travel much less distance for a given time.

The event horizon

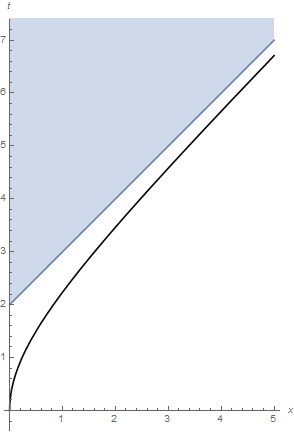

This hyperbolic motion has an interesting property: an event horizon!

Suppose someone is sitting at the place you leave, staying still. They wait for a time of at least \(\frac{1}{\alpha}\) after you leave, then transmit a message using a beam of light. Unfortunately for them, as long as you continue accelerating, that message will never reach you!

This is exactly the same kind of situation as a black hole: people on the spaceship can never receive messages from beyond the event horizon.

This also means that, even though you never travel faster than the speed of light, light beams shone after you from beyond the event horizon will never catch up with you. You’re sort-of outrunning light!

Let’s suppose your spaceship accelerates at \(\alpha=1g\) forever. Restoring factors of \(c\) makes the coordinate time at which your starting point passes the event horizon \(\frac{c}{\alpha}\), which comes out as 353.8 days - just under a year. Anyone on Earth needs to send their message before then, or they’ll never reach you.

As far as you’re concerned on your spaceship, as you accelerate more and more, time on the increasingly distant Earth will seem to pass more and more slowly, gradually approaching the point of 353.8 days but never reaching it. (Light from Earth will also get redder and redder, and this will cause Earth to slowly fade into darkness as well!)

You might recognise the effects I described there: they are exactly the same as what you’d see (from a safe distance!) if you watched someone fall through the event horizon of a black hole. They would seem to slow down and get redder and redder, fading more into darkness and never actually crossing the event horizon. That’s not a coincidence, this is the same phenomenon arising from much simpler physics.

That said, accelerating a spaceship forever is impossible; from the equations we looked at last time, it would require an infinite mass ratio. So at some point, you will have to stop accelerating, and the messages from Earth will start to catch up (very, very slowly…).

What about proper time?

The main reason for pushing yourself as close to the speed of light as possible is to exploit time dilation to make the crew experience much less time than the mission seems to take back on Earth. How does this play in to an accelerated mission?

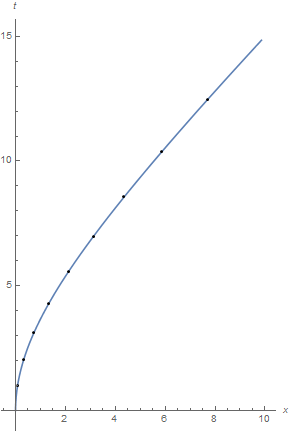

Since we have the ship’s course in a parametric form as functions of the proper time, it’s quite easy to mark out constant-proper-time intervals along the ship’s path…

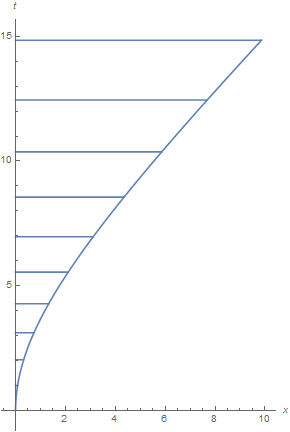

The total elapsed proper time is 10 units (in the same scale as the \(t\) axis), and each unit of proper time is marked on the worldline. We can see the proper time intervals get more and more widely spaced out, just as you’d expect from time dilation as the ship gets faster. To show that more clearly, we can connect them to the time axis, connecting each proper time interval to a corresponding coordinate time interval.

Each interval of proper time takes up an increasingly large chunk of coordinate time. Overall, while only 10 units of time elapse for anyone on board the spaceship, about 15 units of time elapse for anyone who stayed behind.

If we increase the acceleration, even though the ship’s coordinate velocity hardly changes, we can make the same interval of proper time take up arbitrarily longer amounts of coordinate time. For example, tripling the acceleration (which makes the hyperpola look almost like a straight line) causes about 15 times as much coordinate time to elapse as proper time!

This shows why relativistic space missions are necessary to get the same living humans who started the trip to reach distant stars.

Because your coordinate speed can’t exceed the speed of light, even a spaceship which pushes up against the speed of light will take years or decades of coordinate time to reach even nearby stars. To get further away requires coordinate-time durations that are far longer than a human life, even if you could find someone willing to spend centuries on a spaceship.

But if you do push close enough to the speed of light, you find that even as hundreds of years might pass on Earth, a much shorter time will pass for the crew. When they reach their destination, only decades might have passed for them (though the people that they left behind will be hundreds of years dead).

More sensible missions

Constant acceleration would be a terrible way to get anywhere! When you finally reach your destination, you will (assuming you don’t crash into it) zoom straight past into the void at a huge fraction of the speed of light. But at least you’ll get a chance to see it fly by… massively compressed in the direction of travel, and turned all sorts of funny colours by doppler effects.

So you need to slow down at the end! But you probably can’t decelerate to stop at your destination any faster than you accelerated - unlike a car or a train, there’s no surface to rub against and lose all your speed.

That suggests a mission where you accelerate up to the halfway point, then turn your rocket around and decelerate down to zero speed.

Chances are, though, you don’t have enough mass ratio (see part 1) to do that much acceleration. So a somewhat realistic mission will include a period of coasting with your engines off between your acceleration and deceleration phases.

Well, that’s not too hard to set up. We just need to match up the world lines of accelerating, coasting and decelerating spaceships at each point. That means matching the spacetime position and the velocity when you turn your engines off and on, so overall your worldline is nice and smooth.

This post is now very long, so let’s save that for Part 3.

Comments