originally posted at https://canmom.tumblr.com/post/100770...

This explanation of the basic concepts of special relativity (for relativistic rockets part 2) has grown to the point that it needs to be brutally excised and stand on its own.

So, read on to learn about spacetime diagrams, worldlines, Lorentz transformations, four-vectors, metric tensors and some very powerful notation. Which I’m not sure if I’ll actually need for the relativistic rockets posts! But let’s put it all together so I can link back to it if necessary.

Posting this now also gives me a chance to clarify places where I’ve been unclear sooner. So ask if something seems confusing!

Let’s begin.

In Newtonian physics, time is the same for everyone no matter what. You follow a path through space as a function of that absolute time.

In special relativity, time is different to every observer! Oh dear. To accomodate all the coordinate transforms we might need, we’re going to have to put a time axis in all our diagrams, making a spacetime diagram.

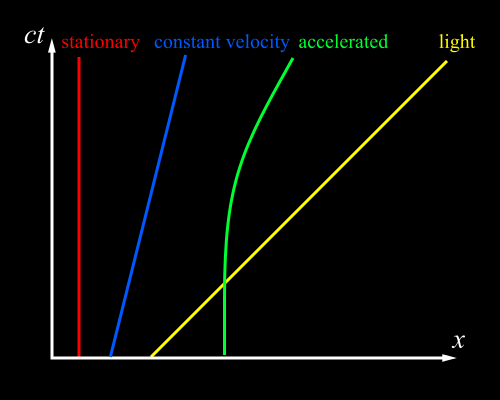

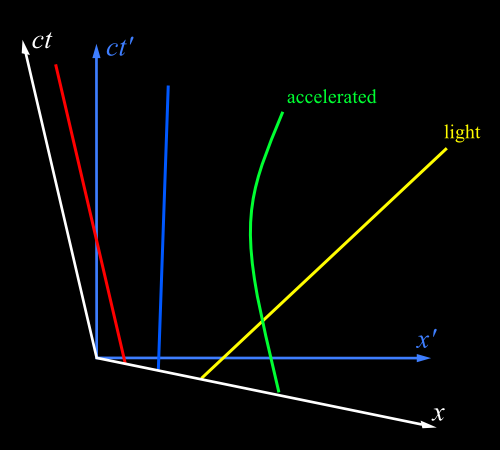

Every spacetime diagram depicts a frame of reference, roughly the perspective of a particular observer or a system of coordinates - it’s easier to explain them by showing them in use. The paths of particles are represented as curves through spacetime, called world lines.

- If something’s not moving in a particular frame, its space coordinates don’t change as its time coordinates do, so it makes a vertical line.

- If something is moving at a constant velocity in this frame, it traces a straight line through spacetime. The gradient of the line is its velocity in the \(x\) direction.

- If something is accelerated (that is, its velocity is changing over time in this frame), it traces a curved line through spacetime.

- No massive object can travel faster than the speed of light. Conventionally, the worldline of light makes a \(45^{\circ}\) line through the spacetime diagram (which comes from plotting \(ct\) on the vertical axis - \(c\) is the speed which never changes between frames, so this makes a lot of sense). So no worldline can have a shallower slope than that, at any point along the curve.

Spacetime diagrams aren’t unique to special relativity. You could just as happily draw one for Newtonian physics! It’s just less informative, really.

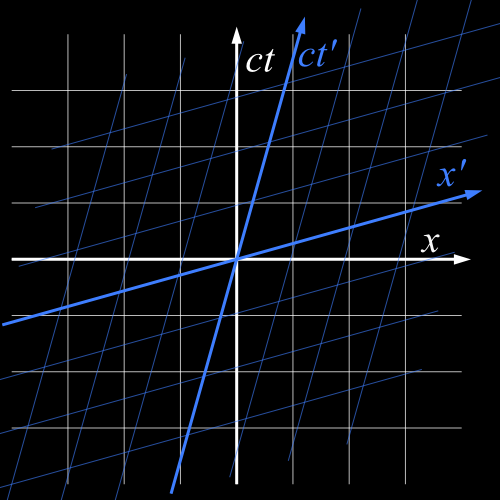

Suppose you look at things in a different frame of reference, the perspective of a different observer moving at a constant speed in the positive \(x\) direction relative to the first. Working out the spacetime positions of the events in this other frame is effectively the same as drawing a new coordinate system over our spacetime.

Conventionally we use primes (\(’\)) to distinguish reference frames, so the white frame is called \(S\) with coordinates \(x\) and \(t\), and the blue frame is called \(S’\) with coordinates \(x’\) and \(t’\).

The blue lines show lines of constant \(x’\) (events which happen at the same location relative to the observer in \(S’\)) and constant \(t’\) (events which the observer in \(S’\) would consider to be simultaneous).

Note that the direction of \(x\) and \(x’\) in 3D space is the same. All that’s different between the frames is the relationship between space and time.

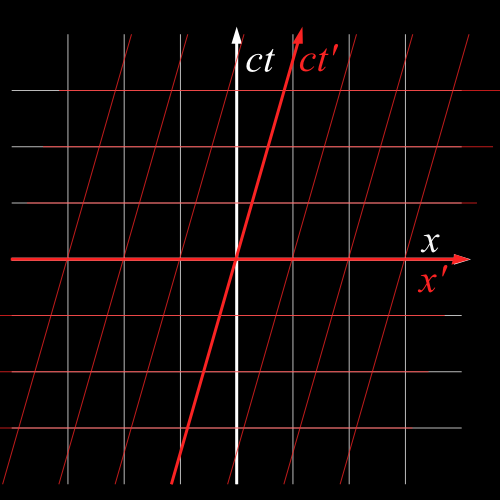

For contrast, let’s use the rules of Newtonian physics instead. In Newtonian physics, the space axis doesn’t move, but the time axis becomes more slanty (it’s a shear transformation)…

This makes intuitive sense (our intuitions being very Newtonian): if someone is moving, as they pass by various things, those things are in the same place as them, so in their frame \(S’\) those things will have \(x’=0\). So if we draw the line \(x’=0\) (the time axis), it will have to be slanted to pass by each of those things at the right time.

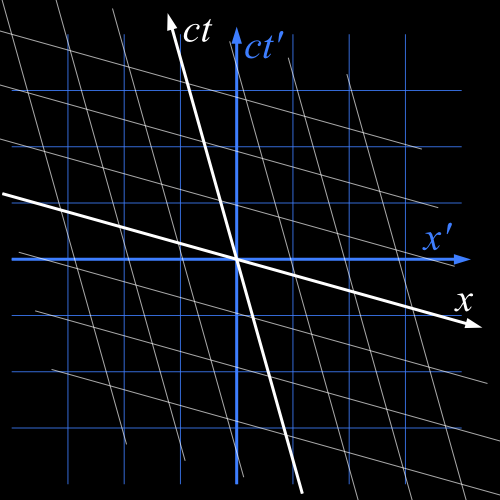

Returning to the relativistic case, we can plot the same diagram so that the \(S’\) frame’s axes are orthogonal. This is the spacetime diagram the observer in \(S’\) would draw.

OK, so what do those world lines look like in the \(S’\) frame, relativistically? Let’s have a look…

We see…

- the angle of the red and blue lines changes, but it remains parallel to the \(ct\) axis. Because \(S’\) is moving in the positive \(x\) direction relative to \(S\), the red worldline has negative slope (i.e. the red particle is travelling in the negative \(x’\) direction in \(S’\)).

- the accelerated curved line is distorted into a slightly different shape. In this frame it starts off going in the negative \(x’\) direction, but turns round to go in the other direction

- the \(45^{\circ}\) line of a ray of light does not change its slope. This is good, because that’s the foundation of all special relativity! (that is, special relativity follows when you say “what if there’s a speed that doesn’t change in any reference frame?”)

OK, so, in summary, in Newtonian physics, we’d express object paths as a function of absolute time. In relativity, there’s no absolute time, just local time in different reference frames, called the coordinate time in each frame.

Proper time

The other important kind of time is the proper time, \(\tau\), for a particular object. This is the amount of time experienced by the particle as it traverses its path through spacetime. The proper time between two events on an object’s worldline can by calculated in any reference frame as the integral of the interval along the path.

The interval is a very useful quantity in special relativity, because it doesn’t change between inertial reference frames (we say it’s Lorentz invariant).

Let’s take take two events (points in spacetime). Say they have Cartesian coordinates \((t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0)\) and \((t_1,x_1,y_1,z_1)\) in some reference frame. The interval (in any reference frame) is given by (assuming a -+++ sign convention) $${\Delta s}^2 = -c^2{\Delta t}^2 + {\Delta x}^2 + {\Delta y}^2 + {\Delta z}^2$$ (where \(\Delta x = x_1 - x_0\) etc.)

Suppose you look at the same two events in the coordinates of a different inertial reference frame: the interval you calculate will be the same.

Why is this the same as the proper time? Well, in the particle’s rest frame, by definition \(\Delta x = \Delta y = \Delta z = 0\), so the interval is just \(-c^2 {\Delta t}^2\). If the particle’s accelerating, that will only be its rest frame for an instant, so you have to add up lots of little intervals for short bits of line to get the total interval.

Because of this, it’s natural to write particle paths by expressing each time and space coordinate as a function of the proper time.

Four-vectors!

There’s a bit more mathematical apparatus to show you before we can fly our spaceship. These are four-vectors.

In Newtonian mechanics, we make a lot of use of Euclidean vectors, which are objects with a magnitude and a direction. When you transform your Euclidean space (rotate it, scale it, whatever) vectors all get transformed in the same way.

In special relativity, we have basically the same idea, but because we are working in a four-dimensional spacetime instead of a three dimensional space, the vectors have an extra component corresponding to the time dimension. The defining property is that they all transform the same way under Lorentz transformations.

Four-vectors also have a magnitude, calculated in the same way as the interval: if you have a fourvector \(\mathbf{A}\) with components \(A^\mu = (A^0,A^1,A^2,A^3)\) then the magnitude squared is $$|\mathbf{A}|^2=A^\mu A_\mu=\eta_{\mu\nu} A^\mu A^\nu=-(A^0)^2+(A^1)^2+(A^2)^2+(A^3)^2$$Just like the interval, the magnitude of a four-vector doesn’t change under Lorentz transformations.

What’s with those funny superscript and subscript \(\mu\)s and \(\nu\)s? Those are the coordinate indices. In Euclidean space, you sometimes end up writing coordinates like \(x_1\), \(x_2\), \(x_3\) with an index in subscript instead of \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\). This lets you write things like $$r^2=\sum_{i=1}^3 {x_i}^2$$ instead of $$r^2=x^2+y^2+z^2$$, and comes in handy when you have other vectors like velocity and acceleration.

Using indices is standard in relativity, because often we want to add things over the quantities. In fact, since we do that literally all the time, we have a convention where we don’t even bother to write the summation signs. If you have two copies of the same index in a product of some quantities, and one is a subscript (like \(x_\mu\)) and one is a superscript (like \(x^\mu\)) that indicates that you need to add up the values of that product for index 0, 1, 2 and 3. This is called the Einstein summation convention. By convention, for spacetime indices like this, we use Greek letters (typically \(\mu\), \(\nu\), \(\lambda\)), and for 3-dimensional space indices, we use Latin letters (typically \(i\),\(j\),\(k\)).

So, for example, if you have some quantity \(x_\mu x^\mu\), that means the sum $$x_\mu x^\mu = \sum_{\mu=0}^3 x_\mu x^\mu = x_0 x^0 + x_1 x^1 + x_2 x^2 + x_3 x^3$$

The superscript and subscript indicate the difference between ‘covariant’ and 'contravariant’ components. Most of the time we don’t use those motuhfuls though, and just talk about 'downstairs’ and 'upstairs’ indices. That’s very important in general relativity, and more important if you’re building this rigorously from the ground up.

For our purposes, things are much simpler! We just need to know that you can raise or lower an index by multiplying it by a thing called the metric tensor which (in special relativity) is written \(\eta_{\mu\nu}\) or \(\eta^{\mu\nu}\). With the -+++ sign convention, the components (in both cases) have the value 0 if \(\mu\neq\nu\), -1 if \(\mu=\nu=0\) and +1 if \(\mu=\nu\neq0\). And we have, in general, \(x_\mu = \eta_{\mu\nu}x^\nu\) and \(x^\mu = \eta^{\mu\nu}x_\nu\).

To expand that out more clearly, what this amounts to is that \(x_0=-x^0\), \(x_1=x^1\), \(x_2=x^2\) and \(x_3=x^3\).

Another important thing about the metric tensor: \(\eta_{\mu\nu} \eta^{\mu\nu} = (-1)\times(-1) + (1\times1) + (1\times1) + (1\times1)=4\).

ok but why

The reason to use this notation is that, because of the way covariant components and contravariant components transform under the Lorentz transform, any expression you write following the rules will be true in every inertial reference frame, not just a particular frame!

The important rule: Every index…

either

- must be be paired up with a corresponding upstairs (if it’s downstairs) or downstairs (if it’s upstairs) index (a 'dummy index’)

or

- it has to appear on both sides of the equation in every term, and have the same 'upstairs’-vs-'downstairs’-ness on each side (a 'free index’)

So for example, here’s a complicated expression that obeys the rules…

$$A^\alpha B^\beta C^\gamma = {D^\alpha}_\delta E^\delta F^{\beta\gamma} + E^\alpha G^{\beta\epsilon} {H_\epsilon}^\gamma$$

All the terms have upstairs \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) free indices, and every other index is in a matched upstairs/downstairs pair in the same term. (If we wanted to, we could use the same symbol for both pairs of dummy indices in the two different terms, or we could use different symbols to make it extra clear they’re distinct).

Here’s another example (the formula for Christoffel symbols, which you might use in general relativity - I’m not going to try to explain what that is used for here!):$$\Gamma^\lambda{}_{\mu\nu} = \frac{1}{2}(g^{\lambda \xi}\partial _\nu g_{\xi\mu} + g^{\lambda \xi}\partial _\mu g_{\xi\nu} - g^{\lambda \xi}\partial_\xi g_{\mu\nu} )$$

Now you know roughly what a four-vector is and the notation that we use for them. That’s not the same as getting familiar with using this notation, for which you would need to practice a lot.

OK, so, I’m defining four-vectors here because it will likely feel natural to use four-vector notation in upcoming relativistic rockets posts. I don’t know yet! This might not be needed at all. But you’ve learned something about relativity I hope? Hmm.

Comments